2014 Farm Bill Signed Into Law: Sodsaver Provision a Win for Sage Grouse & Ranching

Eastern Montana rancher Bill Milton is pleased to see a new sodsaver provision in the Farm Bill of 2014, signed by the President today. He runs a grass-fed cattle operation near Roundup, that’s on the edge of important habitat for sage grouse.

Proactive Sage Grouse Conservation: A Closer Look at U.S. Secretary of Interior Sally Jewell’s Visit to the Bord Gulch Ranch

February 7, 2014

Bi-State Sage Grouse News: Three Federal Agencies, Public Come Together on Fence Marker Project to Prevent Sage Grouse Mortalities

February 11, 2014

Contact:Deborah Richie, SGI Communications Director

(406) 370-7556: info@sagegrouseinitiative.com

Dave Naugle, SGI Science Advisor, Univ. of MT

(406) 240-0113: david.naugle@umontana.edu

Friday, February 7, 2014

Eastern Montana rancher Bill Milton is pleased to see a new sodsaver provision in the Farm Bill of 2014, signed by the President today. He runs a grass-fed cattle operation near Roundup, that’s on the edge of important habitat for sage grouse. The provision will reduce the incentive to convert native sagebrush and grasslands to tilled crops, which do not support sage grouse or livestock grazing.

“We just don’t want to break up any more grass,” Milton said. “What remains of our native grasslands is a high priority to keep right side up.”

“Over the past few years, high crop prices and high land values have pushed crop production onto every available acre, including some of our last, best, prairie habitat,” said Dave Nomsen, vice president of governmental affairs for Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever, strong partners of the Sage Grouse Initiative.

“This habitat is essential for upland birds and waterfowl,” Nomsen said. “Fortunately, the Farm Bill passed today does include a strong sodsaver policy, and while the provision is limited to six states, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota, it represents a compromise that will help save native prairie in the states where it is most threatened.”

Sodsaver reduces the federal crop insurance subsidy available to landowners by 50 percent for four years on any lands they convert from native prairie to cropland. Under the new Farm Bill, landowners are still allowed to convert prairie, but the profitability depends on free-market economics, not agricultural subsidy.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service identified sodbusting as the top threat to sage grouse in Montana and the Dakotas. Addressing this threat will be a major factor in the Service’s 2015 decision on the need to list the sage grouse under the Endangered Species Act.

The Service relies on the Conservation Objectives Team (COT) report to inform its decision on what has changed for the sage grouse since 2010, when the species was found warranted for listing, but precluded by other higher priority wildlife in trouble.

The COT report specifically recommends: “Revise Farm Bill policies and commodity programs that facilitate ongoing conversion of native habitats to marginal croplands (e.d. through the addition of a ‘Sodsaver’ provision), to support conservation of remaining sagebrush-steppe habitats.”

This regulatory mechanism goes into effect today with the President’s signature. Montana harbors almost 20 percent of the world’s remaining sage grouse, second only to Wyoming. The state also ranks first in privately owned sagebrush habitats out of 11 western states, with 64 percent of the habitat on private lands, like Milton’s ranch and many others in eastern Montana.

Milton said his operation benefits from an easement through the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Grassland Reserve Program that ensures the native grasslands remain as grasslands.

“We are hoping that with good conservation practices working with NRCS and good grazing practices the species habitat can be conserved without an endangered species listing,” he said.

Milton has seen firsthand the loss of thousands of acres of native grasslands and shrublands converted to croplands over the past 30 years in both Musselshell County where he lives, and to the north in Petroleum County. He points out that the best farmland was tilled up long ago and what remains tends to be marginal and unsustainable for growing crops. He doesn’t think it’s right to subsidize practices that encourage plowing up what’s left of the prairie.

Science Informs Solutions

Dave Naugle, SGI science advisor and professor at University of Montana, has data in hand that demonstrates how plowing lands reduces sage grouse numbers. He works closely with the University of Montana and The Nature Conservancy to investigate the sodbusting risk and then develop strategies to prioritize conservation efforts.

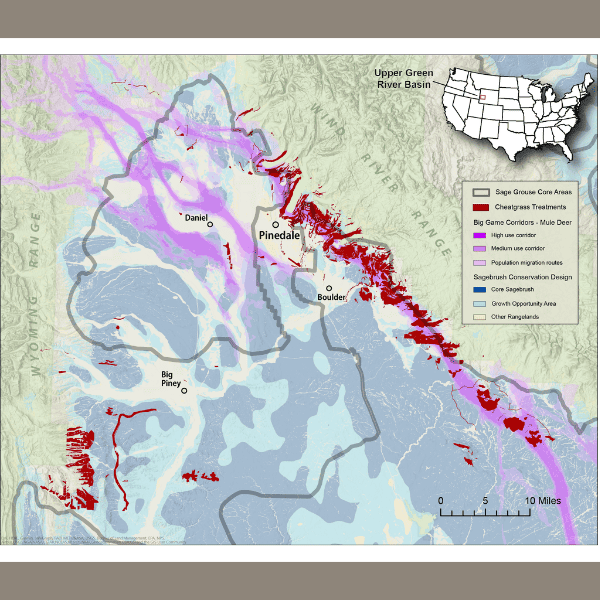

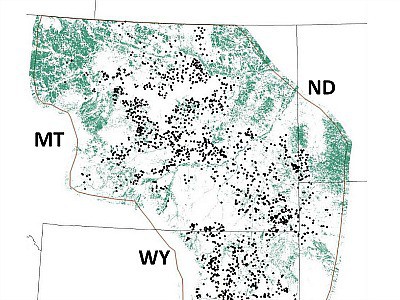

A map of eastern Montana and the Dakotas shows sage grouse lek (breeding) locations falling on native prairie with none on the green-colored lands converted to wheat and other crops.

“Sage grouse hate fragmentation of their habitat,” Naugle said. “They need vast sagebrush-steppe to survive.”

To help keep it that way, he and his colleagues have used overlays of maps to identify the sage grouse strongholds at highest risk of conversion to croplands. They can then efficiently pinpoint where to help ranchers who wish to voluntarily enroll in rotational grazing and conservation easement projects.

“The sodsaver is a game-changer for halting conversion of prairie to cropland,” Naugle said. “The pendulum has now swung in favor of ranching and conservation.”

Sage grouse breeding lek locations in black. Green areas converted to croplands. Research from Joe Smith, graduate student in Wildlife Biology, University of Montana

Converting sagebrush-steppe into cropland —or sodbusting–is the #1 threat to sage grouse habitat in Montana and the Dakotas. Photo in Montana, by Jeremy Roberts, Conservation Media