(Photo right by Associated Press)

Last week, High Country News published an in-depth story on how people from all over the West are working hard to keep the bird off the Endangered Species List. Senior editor Jodi Peterson does an excellent job of introducing readers to the conservation history of sage grouse, and the landscape-scale collaborative efforts underway to save this unique bird and its dwindling habitat. The story features quotes from Sage Grouse Initiative partners, and highlights our voluntary conservation projects with landowners.

Want to listen instead of read? Tune into this radio interview with HCN editor Jodi Peterson on sage grouse, which aired last week on KDNK’s Sounds of the High Country.

The Endangered Species Act’s Biggest Experiment

Will an unprecedented collaborative effort be enough to finally save sage grouse?

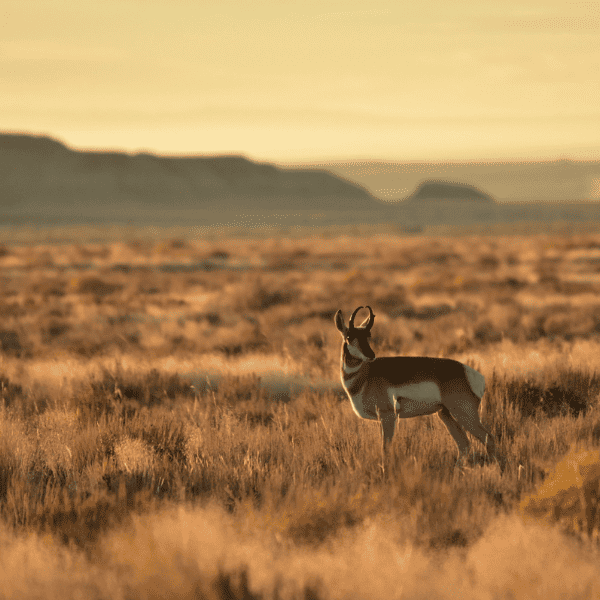

In late April, the hills of Cross Mountain Ranch, near Craig, Colorado, are already dry; the only snow in sight caps the higher peaks on the horizon. A pond sparkles in the sun, and to the west, where the land rises in ridges, dark patches of juniper finger down the draws. On the crest of the hill where I stand, something catches my eye in a pile of rocks. It’s a greater sage grouse egg, buff-green with brown speckles.

In late April, the hills of Cross Mountain Ranch, near Craig, Colorado, are already dry; the only snow in sight caps the higher peaks on the horizon. A pond sparkles in the sun, and to the west, where the land rises in ridges, dark patches of juniper finger down the draws. On the crest of the hill where I stand, something catches my eye in a pile of rocks. It’s a greater sage grouse egg, buff-green with brown speckles.

Peering into its sand-crusted interior, I imagine a tiny striped chick emerging, toddling hopefully after its mother in search of food. But biologist Chris Yarbrough sets me straight: A raven probably devoured this one, he says, turning the shell over on his palm. A hatchling would have pushed out the egg’s large end; here, the middle is crumpled inward. I look again, my cheerful fantasy replaced by a scene from Jurassic Park — the one where the T. Rex shoves its head into a Land Rover to try to extract screaming children.

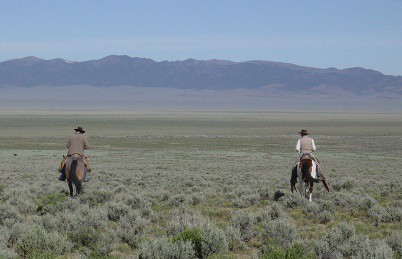

Aside from this particular chick, though, Cross Mountain’s grouse seem to have it pretty good. Last winter, a federal program called the Sage Grouse Initiative helped permanently protect 16,000 acres of prime habitat here through a conservation easement. The property’s abundant sagebrush provides food and cover for grouse, and its thick grass helps camouflage nesting hens. Ranch manager Rex Tuttle, a slight, soft-spoken 45-year-old, points out the pipes he installed from the pond to watering holes down valley; they feed wet meadows, where grouse chicks can fatten on insects. In the far distance, sheep graze; Tuttle says he’ll shift them to higher pastures in June to let the grass here go to seed, so it can shelter grouse this year and grow lush again next year.

He’ll do the same on the neighboring ranch, where he grew up and where another 15,000 acres have been under easement since 2012. Add in a third easement and neighboring federal lands, and a quarter-million acres here are now protected to support grouse and other wildlife.

It’s a conservation outcome that few could have imagined in the 1990s, when biologists first realized that sage grouse were in trouble across their range. Before European settlement, sagebrush covered more than 500,000 square miles; today, oil and gas development, renewable energy projects, subdivisions, wildfire, invasive species and poorly managed grazing have whittled it down to about 250,000 square miles scattered across 11 states. Perhaps 400,000 grouse survive, down from as many as 16 million.

Read the full HCN article here*

*free online subscription required

In late April, the hills of Cross Mountain Ranch, near Craig, Colorado, are already dry; the only snow in sight caps the higher peaks on the horizon. A pond sparkles in the sun, and to the west, where the land rises in ridges, dark patches of juniper finger down the draws. On the crest of the hill where I stand, something catches my eye in a pile of rocks. It’s a greater sage grouse egg, buff-green with brown speckles.

In late April, the hills of Cross Mountain Ranch, near Craig, Colorado, are already dry; the only snow in sight caps the higher peaks on the horizon. A pond sparkles in the sun, and to the west, where the land rises in ridges, dark patches of juniper finger down the draws. On the crest of the hill where I stand, something catches my eye in a pile of rocks. It’s a greater sage grouse egg, buff-green with brown speckles.