Keeping Water In Colorado’s Gunnison Basin

A collaborative partnership using innovative techniques to restore wet meadows in the Gunnison Basin is paying off for people and wildlife.

Take This Quiz To See If You’re A Sage Whiz | Pygmy Rabbit

June 7, 2017Prairie-chicken Restoration Efforts Take Flight in Southeast Colorado

June 19, 2017

Rancher Jim Cochran moves cattle across sagebrush range in Gunnison Basin. Jim is a member of the collaborative Gunnison Climate Working Group. Photo: Jaci Cochran

Partnership to restore wet meadows is paying off for people and wildlife

by Brianna Randall

“This project is a ‘no-lose’ strategy. By retaining moisture, we reduce soil loss, build resiliency, and increase forage for livestock. It’s bigger than any one species.” ~Liz With, NRCS

Why water matters

In southwestern Colorado, the Gunnison Basin stretches across 2.5 million acres of gorgeous montane sagebrush country. This Rocky Mountain watershed ranges from 7,000 to over 14,000 feet in elevation, and is spread over three counties.

The Gunnison Basin’s economic mainstays are livestock grazing, recreation, and tourism. In addition to agriculture, hunting and fishing provide millions of dollars that support the local economy. The region’s diverse landscape provides clean water and air for the 23,000 people who live in the basin, along with vital habitat for wildlife.

Although only 15% of the Gunnison Basin is private land, these acres are some of the most important habitat for the threatened Gunnison sage-grouse along with a host of other wildlife species. Ranchers own most of the wet habitat along streamsides. These “green lines” sustain birds and big game, as well as the ranching operations that are the backbone of the local communities.

That’s why, five years ago, the Gunnison Climate Working Group launched the Wet Meadow Restoration Project to improve natural water storage for both working lands and wildlife.

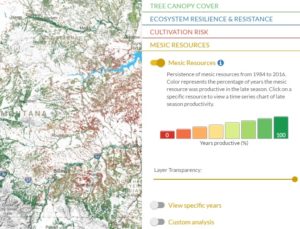

This collaborative project in the Gunnison Basin is a perfect example of the proactive, voluntary conservation practices that SGI and our partners are now using to enhance Emerald Isles across the West’s sagebrush desert. This spring, the NRCS-led Sage Grouse Initiative released our Mesic Conservation Strategy and associated tools to help ranchers conserve the wet, green places that sustain life on the range.

The project in the Gunnison has enjoyed remarkable success through locally-designed, innovative conservation techniques. In just five years, partners have installed 1,112 wet meadow restoration structures, one-third of which are on private land.

Wildlands Restoration Volunteers build a “one rock dam” that will slow down and spread out water. Photo: Betsy Neely

Improving natural water storage

“Restoring degraded wet meadows and streams is some of the most important habitat improvement work we can be doing in the West,” says Nate Seward, a terrestrial biologist with Colorado Parks and Wildlife. “There’s clearly a benefit in retaining more water, improving water quality, and increasing productivity and forage for livestock and big game.”

Seward is a member of the ad-hoc Gunnison Climate Working Group, which aims to prepare nature and people for change. This locally-led group formed in 2009 after The Nature Conservancy of Colorado hosted a two-day workshop to discuss how best to prepare the basin’s rural communities for problems associated with more frequent droughts and floods.

Recognizing the importance of maintaining the Gunnison’s biodiversity as well as its vital agricultural communities, the Conservancy applied for funding from the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2011 on behalf of the group to build the resilience of wet meadows in the region.

“We wanted to work at a scale large enough to help sagebrush-dependent wildlife like the Gunnison sage-grouse, deer, and elk, as well as the ranchers who depend on this landscape for their livelihoods,” says Betsy Neely, Climate Change Program Manager for the Conservancy’s Colorado Field Office in Boulder.

Wet meadows, considered “mesic habitat,” support sage grouse chicks and livestock during the dry summer months. Photo: Brianna Randall

Many riparian and wet meadows in the basin have been degraded by erosion and past land use activities, resulting in lowered water tables and deep gullies. The Gunnison Climate Working Group was concerned that increased droughts and more intense precipitation and runoff events would further impair these vital wet areas. In addition, local partners realized that a lack of high-quality mesic habitat was a limiting factor in the sage grouse life cycle.

The goal of the Wet Meadow Restoration Project is to slow down and spread out the water that’s already on the landscape, whether it’s snowmelt, a creek, or a small trickle. To do this, the group’s many partners are installing a variety of simple restoration structures that capture sediment, raise the water table, and reconnect streams to their floodplains. Capturing sediment allows plants to grow in the wetter soil, which improves forage for livestock and wildlife.

But first the Gunnison Climate Working Group needed to prioritize where to work, since they had limited funds and a very large landscape.

Using science to maximize resources

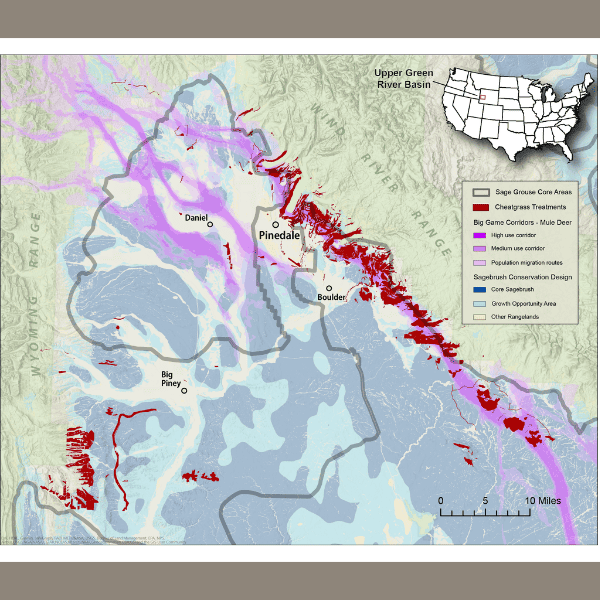

The SGI Interactive Web App now features a Mesic Resources layer that shows the “greenness” of wet habitats rangewide. Partners in Gunnison used a similar approach to prioritize wet meadow restoration sites.

Like SGI’s new mesic resources layer on our Interactive Web App, the group used NDVI as a way to measure the “greenness” of wet habitats. Teresa Chapman, GIS Manager for The Nature Conservancy of Colorado, looked at satellite data for all of the stream reaches in the Gunnison Watershed to compare wet versus dry years since 2000.

Chapman located the places that were “very green” during wet years, but didn’t “green up” at all during drought years. These were the most at-risk areas given changing climactic conditions, and had the best potential for responding well to restoration efforts.

On top of that data, Chapman added in the locations of known sage grouse leks (breeding sites). This helps the group target places where keeping more water on the landscape would “give the birds a leg up” during difficult climactic years, she explains.

Chapman’s analysis serves as an important starting point for evaluating and prioritizing where to invest resources in order to increase the overall resilience of the region’s rangeland.

“For us, increasing resilience on the landscape means increasing the wetness of meadows and riparian areas during drier periods. To do that, we slow down and spread out the water flowing through the system to increase wetland size and the cover of wetland plant species,” says Chapman.

In addition to prioritizing treatment sites, the group uses careful, science-based monitoring to help adjust and maintain the structures. For instance, a few of the sites have required a second layer of rocks, especially after a recent flash flood came through one drainage. Other sites may take longer to grow new vegetation based on lower amounts of precipitation.

“We don’t just put the structures in and walk away,” says Chapman. “The highest success rate means tweaking the structures until they work best for each landowner and each landscape.”

Simple rock structures help store water in the soil, improving forage and late-season water availability in sagebrush rangelands. Photo: Andrew Breibart

The role of ranchers

“Private ranchers are some of our best champions, because they see results on the ground,” explains Neely. “Their neighbors notice the difference and want to join in, too.”

Neely and the many partners and funders of these projects recognize that it’s a risk for landowners to try out new restoration practices. But the early adopters in Gunnison can’t speak highly enough about the positive results.

“I ran into the very first landowner we worked with at a coffee shop,” says Neely. “He came over with his phone, and I thought he was going to show me pictures of his kids. Instead, he showed mepictures of how much the grass has grown in his meadows after he built the structures on his ranch!”

That same rancher helped train volunteers and partners in how to install and build wet meadow restoration structures. These trainings help ensure high-quality results.

Liz With of the NRCS works with ranchers like Greg Peterson, pictured here, to conserve wet meadows and other important rangeland. Photo: Jodi Stemler

Liz With represents the Natural Resources Conservation Service on the Gunnison Climate Working Group and helps ranchers find cost-share to install these structures.

“This project is a ‘no-lose’ strategy,” says With. “By retaining moisture, we reduce soil loss, build resiliency in plant communities, and increase forage for livestock. It’s bigger than any one species.”

According to With, the ranchers involved in this project have a strong land use ethic. These landowners see the importance of storing more water in the ecosystem, which can be used later in the season. Not only do the structures help maintain a good mix of plant species that provide nutritious forage for their cattle, it also keeps noxious weeds at bay – a problem that often “ends up costing ranchers a pretty penny,” she notes.

She receives phone calls from other NRCS field offices all across the western U.S. asking how to replicate the restoration work. With believes that the opportunity to transfer these wet meadow conservation practices across the West is “limitless and overwhelmingly beneficial.”

“It’s been amazing to see partners pulling together,” says With. “This is really a collaborative effort where people want to see the most effective treatment go in.”

Western Colorado Conservation Corps field crew and project team members celebrate the completion of a Zuni bowl and one rock dam. Photo: Andrew Breibart

The value of volunteers

Building over 1,000 rock structures requires a lot of helping hands. The Wet Meadow Restoration Project attracts volunteers of all ages from across the state. Both the Western Colorado Conservation Corps and Wildlands Restoration Volunteers have been integral for providing the field labor required to build these rock structures.

“Personally, I really enjoy connecting people to the land – especially the kids that come from tougher backgrounds,” says Nate Seward from Colorado Parks and Wildlife. “Everyone’s pulling their weight, getting their hands dirty, and working together toward one goal.”

Although the restoration structures usually don’t require bulldozers or excavators, they do require a delicate touch to ensure the rocks are stacked correctly and tightly.

“It’s a lot like masonry work,” says Seward. “We key together rock like a puzzle. There’s an art to knowing where to place it and how to build it.”

The idea is to place the rock structures where the water will flood over top of them, rather than veering around them and cutting into the streambanks, which creates more erosion. These structures were designed by Bill Zeedyk of Zeedyk Ecological Consulting and Shawn Conner, restoration ecologist with BIO-Logic, Inc, both of whom help train volunteers.

It usually takes about a week to install wet meadow restoration structures in a whole drainage, since that yields the biggest ecological benefits. In general, volunteers and resource managers install between 20 to 40 structures 5 to 20 feet apart, depending on the stream system. The structures are usually less than one foot in height, and designed to fit individual stream reaches.

Early on, the collaborative group decided to focus on choosing project areas that cover an entire drainage because that yields the most ecological benefit. They almost always span across both public and private land, which requires concerted teamwork.

By engaging youth and adult volunteers, these projects instill a valuable land ethic in participants as well as restore wildlife habitat.

Several of the volunteers have returned year after year to participate in the project. They enjoy seeing the results from their hard work the previous year: grass sprouting atop the rocks they fit together.

Gay Austin, BLM, and others conduct vegetation monitoring at the Wolf Creek, BLM site. Photo: Renée Rondeau/CNHP

Monitoring results

One of the best parts about this type of habitat restoration is that its easy to see – and measure – the ecologic response. And it doesn’t take long to notice a positive change.

Renee Rondeau, an ecologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Gay Austin, ecologist with BLM, and Suzanne Parker, biologist with USFS — all members of the Gunnison Climate Working Group — have been monitoring restoration treatments since the project’s inception in 2012. They take photos and record the wetland plant species present, as well as the amount of land area that the plants occupy.

These scientists collect baseline information before the structures are built, and also compare restored areas to control sites (nearby untreated areas) to objectively evaluate whether the practices are working.

“The group’s goal was to increase wetland species cover by 20 percent at each structure. We’ve definitely exceeded that,” she says.

At sites built in 2012, Rondeau’s data shows an average increase of 160 percent in wetland species cover in just four years at the restored sites.

Typically, most restoration sites begin to show a significant response around three years after installing the structures. But they generally see some response within the first year. Some sites plateau in terms of new wetland growth may require a second layer of rock to further boost water storage and plant production.

One reason these structures are popular is because they blend in with the natural environment. If placed correctly, the rocks will eventually disappear, replaced by soil and grass.

“Some of our structures are hard to see now through all the vegetation, which means they’ve done their job,” says Rondeau.

Rondeau believes that the project’s impressive results are because the Gunnison Climate Work Group “co-produced the science” up front in order to integrate the planning, the implementation, and the monitoring stages.

“From the ground up, we’ve had the scientists and practitioners at the table,” she says.

The scientists plan to keep monitoring early-adoption sites as well as the rock dams that continue to be built each year in order to better understand the rate of change in these wet meadows.

The restoration structures are designed to “disappear” once they do their job, since they capture sediment that encourages new plant growth atop the rocks. Photo: Nate Seward

The power of partners

All of the partners in the project agree: the recipe for its success stems from the strong team of diverse players dedicated to making it work. From public landowners to ranchers, nonprofits to foundations, county governments to native plant societies – everyone in the Gunnison Basin has pitched in to restore the area’s valuable water resources.

This local, community-based approach has made all of the difference.

“No way could I do this myself. Being able to work across ownership boundaries to restore an entire drainage truly provides the resiliency we need,” says Seward.

The Gunnison Climate Working Group hopes to leverage the success of these wet meadow restoration projects beyond the Gunnison Basin.

“There are so many watersheds in need of restoration across the West. These methods have great potential to work in other places, too,” says Neely.

This week, the Sage Grouse Initiative is hosting our annual workshop in Gunnison, Colorado, which includes a field trip to take biologists and range managers from 11 western states to see the results of these wet meadow restoration structures on private ranches. In addition, SGI field team members will attend a training to learn how to build these rock structures to benefit working lands and wildlife across sagebrush country.

“We’re excited to showcase the work of the Gunnison Climate Work Group during the SGI workshop,” says Seward. “Water is the blood of these arid systems. This project is breathing new life into degraded areas.”

Read the 2017 Executive Summary of the Gunnison Wet Meadow Restoration Project

Check out this “Cheap and Cheerful Stream Restoration” webinar

Learn more about SGI’s new mesic conservation strategy

Wet meadow restoration structure at Flat Top in Gunnison Basin. Photo by Shawn Conner.