Las Vegas Sun, Tuesday, Dec. 24, 2013

The fate of the cow and the sage grouse in the West are inescapably linked. The habitat needs of the grouse are the same as those of the cow. If we want to save the birds, the best strategy is to keep our ranches intact and working, not up for sale to developers or bankrupt.

The comment period for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service proposal to list the bi-state population of sage grouse as a threatened species ends Feb. 10. Those are the birds on the California-Nevada border that are considered separately from the greater sage grouse in 11 Western states.

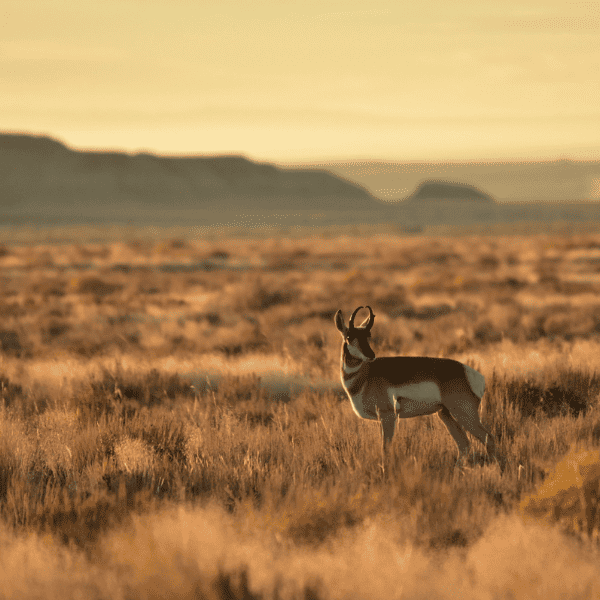

Listing the birds under the Endangered Species Act would be a disaster. Don’t get me wrong. Sage grouse are in trouble from their habitat being broken up. The birds, like ranchers, need lots of elbow room. Put up houses and build roads and they’re gone. Allow juniper and pinyon trees to invade the sagebrush and the birds vanish, too. They like treeless, see-forever range with plentiful native bunchgrass and sagebrush. So do I.

But here’s the problem. A listing could well have the opposite result from its intended purpose to help the bird, throwing our ranch economies into a tailspin and sending the sage grouse spiraling toward extinction.

The alternative to an ESA listing is brilliantly simple, but I bet most people don’t even know the solution is right in front of their noses. For the past decade, ranchers and others from all walks of life collaborated with agencies to identify threats and then reduce or eliminate them. Agriculture and other conservation partners invested tens of millions of dollars over the past three years to conserve and enhance private land strongholds for the grouse. It’s the 2012 bi-state action plan for sage grouse. Yep, a plan that works.

Private lands you say? Who cares? After all, the bi-state bird habitat is 92 percent public land. But here’s the clincher. That 8 percent of private ranch land tends to be water- and soil-rich. It makes sense. The early homesteaders picked the best spots, and those became private. Every summer, sage grouse broods head over from public lands to irrigated hayfields and pastures. Without these private lands associated with Western ranches, the birds just won’t make it.

Some well-intentioned people might think if we stopped grazing the public lands, sage grouse will be fine. Not so, for many reasons. Here’s a huge one. Public land leases are a vital part of many Western ranch operations; without them many of us wouldn’t be able to make it financially on private lands alone. The only option is to sell the land for development. That would be a sad day for ranchers and sage grouse (along with many other critters), and for millions of people who rely on the water that ranches conserve for all of us.

I’d hate to see Smith Creek Ranch ever developed. I’m in Central Nevada, not the bi-state area, but I worry. The sage grouse that fly up in a burst of wing power from our wet meadows are an important, valuable part of our life in the Great Basin. Words can’t describe the sense of joy and satisfaction each time I am able to witness this special part of our environment. I’d be devastated to lose the birds and the ranch. The bi-state listing is a test case for what’s ahead a year from now. That’s when a decision will be made whether to list the sage grouse range-wide.Let’s get it right with the bi-state birds. We don’t need complex special rules and exceptions to a threatened listing that pay lip service to our great bi-state plan. The government needs to recognize the stunning momentum and progress happening now. List the bird and you’ll just knock the wind right out of the sails.

The sage grouse itself can teach us all a lesson. This bird flies across public and private lands and sees one landscape. The bird knows instinctively what Aldo Leopold coined as the land ethic. We’re all one community. Take care of the cows and the sage grouse across borders. Work together. Focus on what we agree on. Avoid burdensome regulations. If we do that, we can win the battle. Heck, it might not even be a battle if we roll up our sleeves, stop arguing, and get it done — voluntarily.

Duane Coombs is the ranch manager at Smith Creek Ranch in Austin.

ONE COMMENT ON OPED:

Ranchers can and do co exist with native species. It is not unusual for them to locate nests, tag the area around the best, and farm around it. Some ranchers even dedicate whole fields as habitat or plant feed for migrating animals on wing and hoof. This does not have to be a lose-win or lose-lose situation. When you work with nature, you understand the inner dependence in the relationship and the grandeur of creation.

DOWNLOAD COOMBS-PDF

(SGI photo with story courtesy of Ken Miracle)