New Mexico Range Managers Put Science to Work for Prairie-Chickens

LPCI NEWS RELEASE: For wildlife biologist Randy Howard, a new mapping tool developed by lesser prairie-chicken researchers is an essential part of restoring habitat for grassland-dependent wildlife. Read about this great example of “actionable science.”

New USFWS Collaboration Expands Science Tools To Sage-Steppe

April 10, 2017

How Do Conservation Easements Work?

April 20, 2017Science-based conservation that benefits wildlife and landowners—that’s what the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI) is all about. Over the past few years, LPCI—a partnership led by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service—has helped fund research projects across the southern Great Plains, aimed at better understanding lesser prairie-chicken ecology in order to fine-tune conservation practices.

For wildlife biologist Randy Howard, a new mapping tool developed by lesser prairie-chicken researchers is an essential part of his efforts to restore habitat for grassland-dependent wildlife.

Wildlife biologist Randy Howard adjusts the float system on a wildlife tank at the Bureau of Land Management’s Sand Ranch in New Mexico.

Howard oversees habitat management at the Bureau of Land Management’s Sand Ranch, a 58,600-acre parcel of land 35 miles east of Roswell, New Mexico. Designated as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern, Sand Ranch is specifically managed as habitat for the lesser prairie-chicken.

Howard’s toolbox of conservation practices got major boost with the advent of a digital mapping tool that shows with unprecedented detail the extent and density of woody encroachment on prairie habitat in the southern Great Plains. In New Mexico, most woody encroachment comes from a single species—honey mesquite.

“That mapping layer has been awesome for our planning purposes,” Howard said. “Whenever we’re looking at mesquite treatment, we’re using that layer,” In digital mapping, data is organized in “layers” of information, with each layer relating to a particular land feature.

The effectiveness of the new mapping layer is compounded by another ground-breaking study by a research team under the direction of Dr. Scott Carleton of New Mexico State University. The study is the first to quantify the effects of mesquite on lesser prairie-chicken habitat use. Researchers found that lesser prairie-chickens strongly prefer sites with less than 1% mesquite canopy cover and rarely use sites with more than 15% canopy cover.

Results from that study suggest that removing mesquite in low-density (<15% canopy cover) is essential to maintaining or expanding existing habitat and reducing the threat of habitat loss.

When mesquite moves into prairie grasslands, lesser prairie-chickens move out. Photo: Charles Dixon.

Both Carleton’s research and the mapping tool development were funded in part by the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI). According to LPCI Science Advisor Christian Hagen, the targeted habitat restoration work underway in New Mexico is a great example of “actionable science.”

“This is the interface of research and management, where conservationists identify, fund, and implement habitat restoration in areas that will have the greatest biological effect for prairie-chickens and other prairie-obligate species,” said Hagen.

Howard noted the tangible impacts of this scientific research on his habitat restoration efforts. “This mapping layer, along with Carlton’s research, shifted our thinking to prioritizing treatment of low-density mesquite,” said Howard.

This past year, Howard used the mapping tool to select three leks on Sand Ranch for mesquite treatment. “With the mapping layer, you can really see which leks need immediate attention and where you still have time [to do treatment at a later date].”

Leks are critical habitat sites, where male lesser prairie-chickens gather each spring to perform mating displays, spar with other males, and mate with females. Nesting often occurs within a short distance of the lek site.

Howard’s crew treated all mesquite within a ½-mile-wide perimeter around the three leks. Because the mesquite was low-density, the crew was able to hand-spray it using backpack sprayers.

The next, essential step in restoring that habitat for prairie-chickens will be to remove the dead mesquite carcasses, but that can’t be done for three years, since it takes that long for the mesquite plant’s extensive root system to die.

A tree masticator chews up dead mesquite skeletons, eliminating their vertical structure, which repels lesser prairie-chickens.

In the meantime, Howard will be complete treatment of three other sites at Sand Ranch that were hand-sprayed three years ago. They’ll bring in tree masticators to grind up the mesquite carcasses, using funding from the non-profit Center of Excellence, which supports habitat conservation projects for two species of concern in New Mexico—the lesser prairie-chicken and the dunes sagebrush lizard.

Howard recently received a $677,000 grant from the Center of Excellence, which he will use to treat 10 priority lek sites across eastern New Mexico. The mapping layer figured prominently in the process of selecting the leks. Biologists from LPCI, US Fish and Wildlife Service, New Mexico Game and Fish, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Center of Excellence, and BLM examined the mapping data and made their recommendations.

In addition to helping range managers identify priority mesquite treatment areas, the mapping layer helps in linking core habitat areas. “Using that mapping layer, we’re able to look at the big picture of habitat management, and we can see where we can connect lek sites with one another,” Howard said.

For example, he said, with the three lek sites they just treated on Sand Ranch, the southernmost lek is separated from the other leks by just ten miles. But because there’s a big swath of mesquite in those 10 miles, the southern lek is effectively isolated.

The mapping tool allows Howard to see where to create effective connectivity corridors. “We can blow a path through that mesquite with aerial spraying and follow up with masticators.”

The resulting mesquite-free habitat won’t just benefit lesser prairie-chickens—it will benefit all grassland-dependent wildlife and the livestock that graze there.

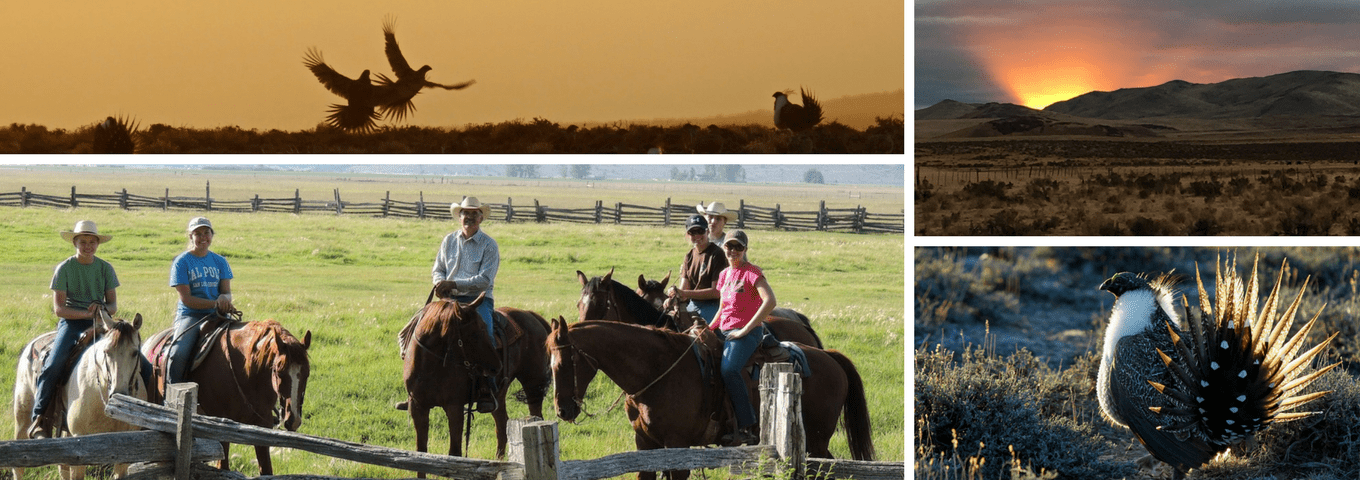

The Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative, led by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, is a partnership-based, science-driven effort that uses voluntary incentives to proactively conserve America’s western rangelands, wildlife, and rural way of life.