Ranchers and Conservationists Combine to Help Sage Grouse

Two national conservation leaders from the USDA-NRCS and the National Audubon Society co-wrote this recent editorial about how targeted, proactive conservation on agricultural lands by private landowners is leading the way in restoring habitat for threatened wildlife species in the West.

Texas Rancher Creates Haven for Lesser Prairie Chickens

September 14, 2015

Building Bridges | Ranchers Are Stewards of the Land

September 20, 2015

(Photo to the right by Ron Francis: Jay Tanner drives cattle on the Della Ranch in Utah.)

Two national conservation leaders co-wrote this recent editorial about how targeted, proactive conservation on agricultural lands by private landowners is leading the way in restoring habitat for threatened wildlife species in the West. Jason Weller, Chief of the Natural Resources Conservation Service and David Yarnold, President and CEO of the National Audubon Society, authored the following article published Sept. 17 in the Salt Lake Tribune.

—

The Tanner family has been ranching in northwest Utah since the 1870s, and their connection to the land runs deep.

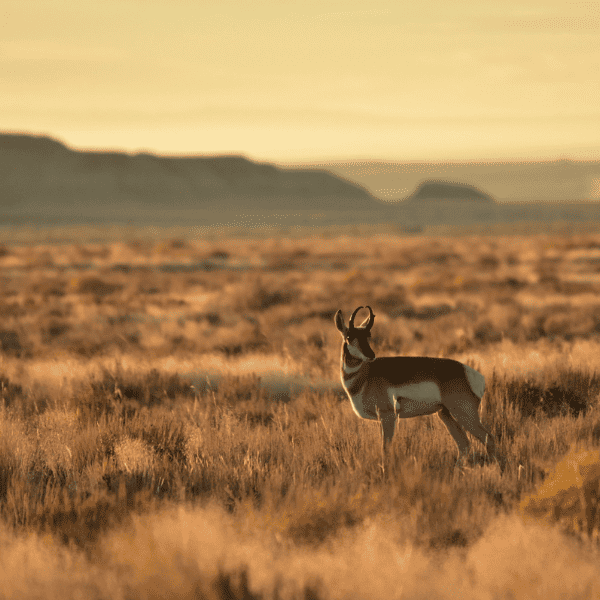

Over the last five years, the Tanners have been working with a partnership called the Sage Grouse Initiative to improve their land for a once-common resident that’s fallen on hard times: the greater sage-grouse. Populations of the iconic Western gamebird, known for its flamboyant appearance and early spring dances, have declined in the last century, and the species’ fate is the subject of intense political battles in Washington, D.C., and across the West.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will decide by the end of the month whether the bird belongs on the federal endangered species list. But the Tanners are doing their part to keep that listing from becoming necessary. They’ve improved over 9,000 acres of their land for the bird, and they’ve adjusted their grazing schedules in order to make sure that sage-grouse are able to nest and raise their young in the spring and early summer.

Their efforts are paying off. In 2014, populations of the greater sage-grouse were up by 20 percent in the county where the Tanners ranch. “It’s almost unbelievable how the native species are coming back,” Jay Tanner told us.

The Sage Grouse Initiative, led by U. S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and with an array of partners including the National Audubon Society, is a powerful public-private cooperative effort that’s achieving results for landowners and for wildlife. Over the last five years, the initiative has worked with more than 1,100 ranches in 11 Western states to improve and protect 4.4 million acres. That’s an area twice the size of Yellowstone National Park. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack recently announced $211 million will be added to the effort. With partner contributions that will bring the total to an estimated eight million acres by 2018.

But this story is about more than the sage-grouse and the West. These farmers and ranchers who are partnering with NRCS, Audubon and others are engaged in an unprecedented level of landscape-scale conservation across the nation. And they have results to show for it.

The Oregon chub recently made history as the first fish species to rebound so much it was removed from the endangered species list. This could not have happened without conservation efforts on private lands, like those of David Budeau of Marion County, Ore. He partnered with government agencies to enroll 30 acres of his land in conservation easements and create fish-friendly wetlands that now host more than 10,000 Oregon chub.

In the desert Southwest, where water woes are causing worries for people and wildlife alike, we’re working towards habitat restoration on private working agricultural lands for the Southwestern willow flycatcher, which is on the endangered species list. But instead of just focusing on the flycatcher, a new initiative will focus resources on the entire ecosystem, benefiting the bird and 83 other species — fish, plants, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals — that depend on a healthy habitat.

So what’s the secret here? It turns out that targeted, proactive investments in conservation on private agricultural lands aren’t just good for wildlife. The same practices that promote habitat creation lead to healthier, more productive working forests, farms and ranches. They improve the quality of water and the resilience of working lands stressed by drought. These practices promote the healthy ecosystems needed for agricultural production to thrive, boosting America’s rural economies.

That’s why landowners are leading the way, and why these kinds of public-private partnerships are the very definition of “win-win” for birds, wildlife, people and the habitats they share.