The Tree that Ate the West | bioGraphic Magazine

by Rebecca Heisman,bioGraphic | When mature juniper cover reaches just 4 percent—picture taking a standard checkerboard and filling in just two and a half of the squares—sage-grouse abandon their leks. Read more about the conifers that are taking over sagebrush rangelands in the West.

“It’s About Working Lands For Agriculture And Working Lands For Wildlife”

August 16, 2016

Kennedy Ranch Conservation Improvements Benefit Both Livestock And Wildlife In Utah

August 23, 2016

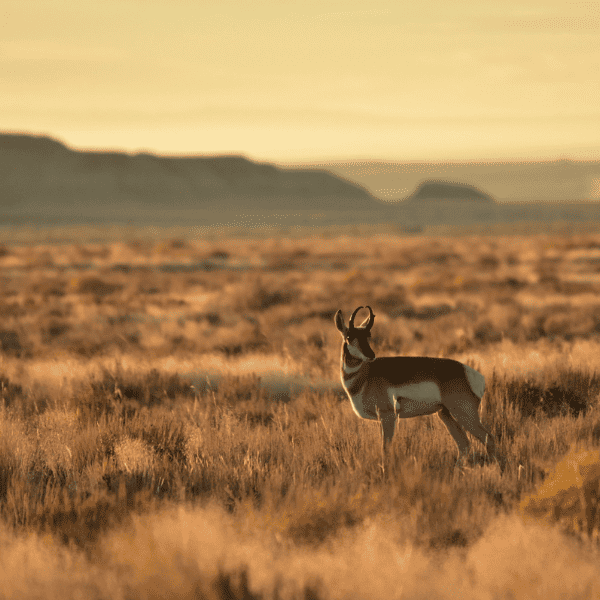

Photo by Kat Whitney, courtesy of bioGraphic Magazine.

The following excerpt is from a story by Rebecca Heisman that appeared here in bioGraphic on August 9, 2016. bioGraphic is a multimedia magazine produced by the California Academy of Sciences.

“We’ve been slowly losing our ranches to these green invaders for a long time,” says John O’Keeffe, president of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association.

No animal is more emblematic of the sagebrush steppe in trouble than the greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). These iconic western birds, about the size of barnyard hens, gather each spring in groups called “leks.” Here, the males inflate yellow air sacs in their chests, spread their fanlike tails, and dance for the approval and attention of the females—a display so show-stopping that many people have dubbed them America’s birds of paradise. Unfortunately, these reproductive spectacles have become increasingly rare as the species’ population has plummeted 80 percent since 1960, primarily due to habitat loss.

Photo by Bob Wick, BLM

The sage-grouse is a kind of indicator species, signaling the health—or lack thereof—of the ecosystem it inhabits. As its name suggests, the sage-grouse depends on sagebrush for food and nesting cover. A number of factors in addition to the juniper invasion have contributed to the bird’s shrinking habitat, including energy development, invasive weeds, drought, and urban expansion. But juniper’s impacts on grouse go beyond the loss of sagebrush: Grouse have evolved to give a wide berth to any tree more than four feet tall, because anything taller than a sage bush represents a potential perch for a predatory hawk.

When mature juniper cover reaches just 4 percent—picture taking a standard checkerboard and filling in just two and a half of the squares—sage-grouse abandon their leks.

Conifers tend to be sensitive to fire, and historically, junipers survived the fires that regularly swept across the arid inland west by carving out niches safe from the flames. They took root in inhospitable patches of habitat where the grasses that fueled the fires couldn’t grow—rocky surfaces and steep slopes with shallow soils and little moisture.

Photo by Kat Whitney

But beginning around 1870, settlers turned large numbers of cattle loose to eat the native grasses that grew among the sagebrush. This left less fuel for fire, and between this and a widespread campaign to suppress fires across the American West, soon nothing was keeping junipers confined to their steep, rocky sanctuaries. Now, when a robin perched on one of those gnarled branches to gulp a juniper berry, chances were good that the seeds would grow undisturbed wherever the bird happened to drop them. Across the region, juniper populations exploded.

Given the opportunity, juniper trees outcompete the grasses and shrubs of the sagebrush steppe. In extreme cases, nothing but bare soil and shallow-rooted invasive grasses remain between the trees, dramatically decreasing habitat quality for many species. Sagebrush-dependent songbirds like the Brewer’s sparrow and the green-tailed towhee have nowhere to nest. Bighorn sheep and pronghorn antelope become more vulnerable to mountain lions, which use junipers as cover to stalk large prey.

Photo by James Davidson

The spread of juniper can also reduce water availability in an already-parched landscape. Despite their drought tolerance, a single mature juniper can consume 10 to 30 gallons a day, pulling water from nearby streams and springs. While this affects native wildlife, it’s had an even greater impact on the cattle ranchers who for generations have come to depend on the sagebrush ecosystem’s natural resources. As water and native grasses become scarce, the number of cattle a piece of land can support plummets.

Depending on the site and how advanced the juniper growth is, the tree’s invasion can decrease the amount of forage by 30 to 90 percent. The Oregon Cattlemen’s Association has called juniper “one of our most noxious invasive species.”

Read the full story and view spectacular photos here.

SGI Resources:

Read studies on conifer removal, including Science to Solutions articles

Map tree canopy cover near you using SGI’s Interactive Web App

Hear stories from the field about ranchers partnering to remove conifers

Learn more about conifer removal priorities in the SGI 2.0 Investment Strategy

Read about our Public Land Partnership with BLM to remove conifers