Photo of a lesser prairie-chicken by Nick Richter.

Just like sage grouse, lesser prairie-chickens decrease as conifers increase

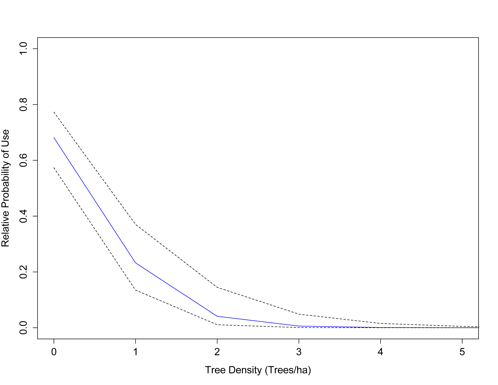

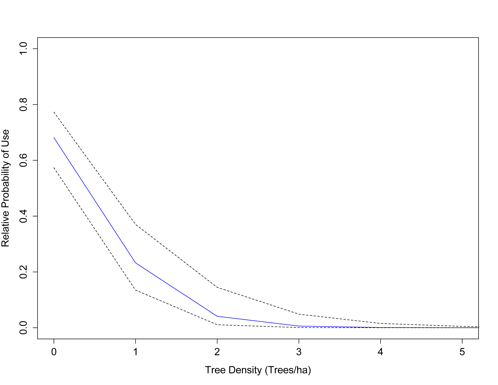

As tree density increases, lesser prairie-chicken nesting declines.

One simple graph says it all: conifer encroachment spells bad news for birds that need intact, wide open spaces. The Sage Grouse Initiative works collaboratively with public partners and private landowners to remove juniper and pinyon removal, since high densities of these conifers negatively impact sage grouse. Now our partner group, the Lesser Prairie Chicken Initiative, has released a Science to Solutions report that shows lesser prairie-chickens decrease when redcedar density increases.

The prairie after redcedars are removed.

The prairie before redcedars are removed.

Woody plant encroachment is a leading threat to remaining grassland habitat in the Southern Great Plains. Natural processes like fire once prevented redcedar encroachment, but fire suppression has led to widespread redcedar invasion and loss of grassland habitat.

Researchers from Kansas State University and the U.S. Geological Survey tracked 58 female lesser prairie-chickens for two years on 35,000 acres of privately owned grasslands in southern Kansas using GPS transmitters. Results from this new study show that female lesser prairie-chickens did not nest in grasslands with more than 1 tree/acre, placed nests at least 1,000 feet from the nearest tree, and stopped using grasslands altogether when tree density reached 3 trees/acre.

Like sage grouse, lesser prairie-chickens require large blocks of structurally-diverse habitat to breed, nest and successfully raise their young. Because of the bird’s landscape-level habitat needs, scientists consider it an indicator species for grassland health. Both SGI and LPCI are funded by USDA NRCS Farm Bill dollars, and use science to help private landowners proactively improve working rangelands for wildlife.