Photo: USFWS Pacific Southwest

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher

This small songbird needs lush riparian vegetation to thrive. Improving the health of these areas benefits the flycatcher and lots of other wildlife.

Wet green places comprise just 2% of the arid western landscape, yet more than 90% of wildlife species depend on riparian areas for survival. The lush plants surrounding the Southwest’s precious rivers and streams harbor hundreds of different wildlife species, rivaling the Amazon’s rainforests in biodiversity.

The southwestern willow flycatcher—a migratory songbird—tells us how riparian habitats. Their answer: not well. The bird was listed as endangered in the Southwest under the Endangered Species Act in 1995 due to habitat loss.

Riparian areas in the desert are disappearing or in rough shape. Water diversions, groundwater pumping, changes in flood and fire regimes, and the spread of invasive plants have drastically changed streamside habitat. Luckily, landowners are stepping up to voluntarily restore riparian areas.

More than 100 landowners have partnered with WLFW to conserve 29,000 acres in Arizona, California, and Utah.

FAST FACTS

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher

Species Name: Empidonax traillii

Appearance: A small, slender flycatcher that’s brownish-olive with a slight yellow tint on the belly and two white wingbars. They are 5-6 inches long but weigh just half an ounce.

Migration: Breeds and feeds in riparian areas of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah each summer, then migrates to Central or South America for the winter.

Nesting: Females weave together grass and plant fibers into a cup-nest, nestling it a few feet off the ground in a willow or other streamside shrub. Mates are monogamous and may re-pair over several seasons.

Song: Best known for its sneezy “fitz-bew” call, flycatchers hatch already knowing their songs rather than learning them from their parents.

Riparian Buddies: Restoring healthy, green streamside plants for the southwestern willow flycatcher benefits 84 other wildlife species.

Non-native conundrum: If native plants aren’t available, these birds will nest in non-native tamarisk or Russian olive—unwanted invaders that can de-water streams. It’s important to also replant native shrubs when removing invasive plants so flycatchers can still breed.

- Southwestern willow flycatchers only live along streams and rivers, in what is called the “riparian zone.”

- The Upper Gila River in New Mexico and Arizona is the type of habitat that southwestern willow flycatchers rely on during their summer breeding seasons. Photo: USGS

proactive, voluntary conservation wins

Producers Are Part of the Solution

Luckily, stewardship-minded ranchers from across the Southwest are stepping up to voluntarily restore streamsides.

Through WLFW, NRCS experts work side-by-side with landowners to develop a conservation plan customized to meet each rancher’s needs, while also helping the southwestern willow flycatcher rebound.

What’s good for these birds is also good for livestock herds: healthy riparian areas offer drought resiliency for ranchers by providing shade and improved water storage.

Examples include revegetating riparian areas, strategically removing invasive trees like Russian olive and salt cedar, developing off-stream water sources for livestock, or managing livestock grazing.

WLFW offers technical and financial assistance for landowners interested in adopting riparian conservation practices through the NRCS Environmental Quality Incentives Program.

Landowners who continue to manage their ranches using NRCS-prescribed conservation practices are ensured regulatory compliance under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for up to 30 years. These contractual assurances give agricultural producers the predictability they need to operate their farms and ranches into the future.

Meet More Riparian Wildlife

The riparian zones in the desert southwest are home to diverse and captivating wildlife. Learn more about these unique species below.

Jumping Mouse

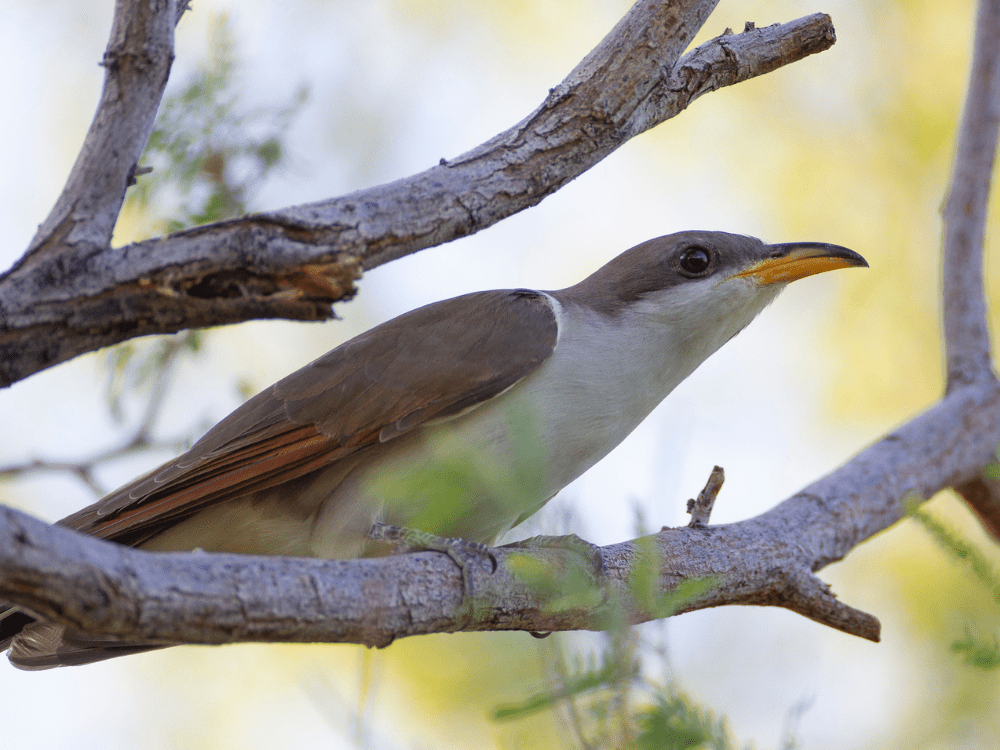

Yellow-Billed Cuckoo

Chiricahua Leopard Frog

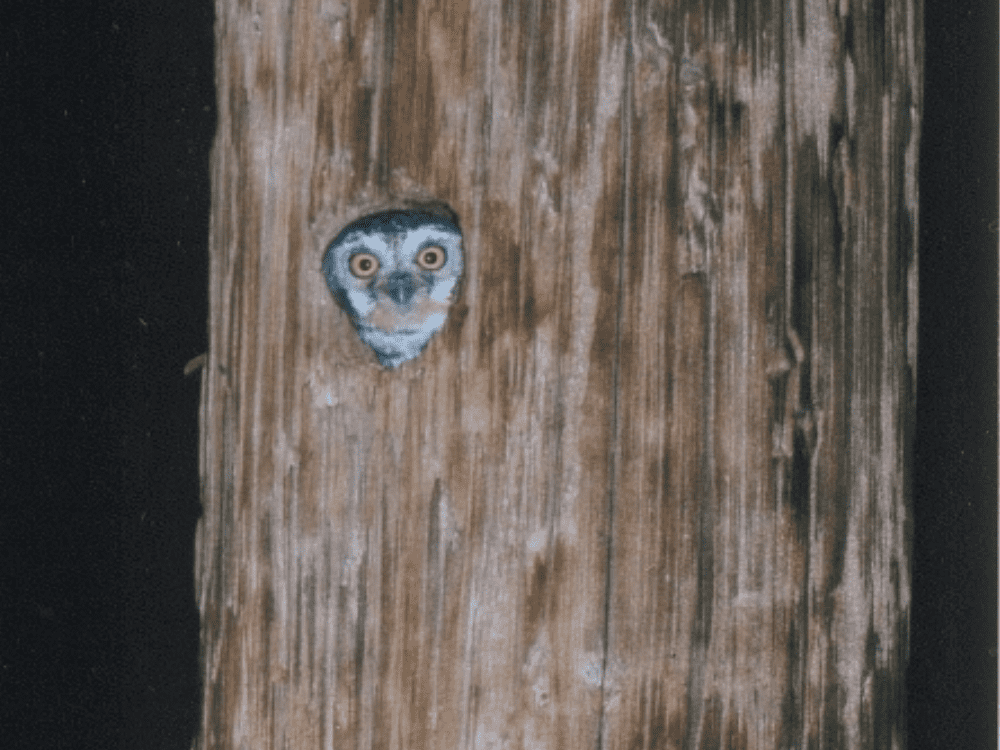

Elf Owl

New Mexico Jumping Mouse

The New Mexico jumping mouse has an extremely long tail and large hind feet. Even though they are only about five inches long, these mice can leap up to three feet!

This endangered mouse is nocturnal, foraging for seeds in dense riparian or wetland vegetation that’s at least two feet tall. It can live up to 8,000 feet in elevation and loves to swim.

Fun Fact: These bouncy mice hibernate nine months out of the year and are only active and awake during the summer!

Yellow-Billed Cuckoo

Its curved yellow bill and long white-spotted tail make this bird easy to identify, particularly since they are larger than a robin. These are one of the few bird species to eat hairy caterpillars—as many as 100 in one sitting!

The cuckoo’s croaking call is fading from the Southwest, as the cottonwood forests along rivers are dwindling.

Fun Fact: Both parents build the nest and incubate their eggs—the male takes the night shift.

Chiricahua Leopard Frog

These 4-inch-long frogs are green with dark leopard-like patterns on their back and legs. Chiricahua leopard frogs need permanent water sources to lay eggs and successfully reproduce, which is increasingly hard to find in the arid Southwest.

Fun Fact: The male’s mating calls sound like a snoring human!

Elf Owl

This tiny owl lives in forests along the southern border of the United States and Mexico. They nest in old woodpecker holes or other cavities to take shelter from heat, rain, and predators. At night, elf owls hunt insects and other small prey.

These owls gravitate toward riparian forests and streamside trees.

Fun Fact: The elf owl is the world’s smallest raptor. It's the size of a juice box!