Migratory Big Game Conservation Highlights the Best of West

Learn more about the USDA’s Migratory Big Game Initiative and how WLFW is helping lead this broad effort in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho.

Prioritizing healthy grasslands leads to more efficient conservation than focusing solely on wildlife

November 6, 2023

NRCS and Partners Work Together to Help Families Keep Their Land Green-Side Up

December 13, 2023USDA’s Migratory Big Game Initiative is working to ensure the West’s big game always have room to roam.

From mule deer and elk to pronghorn, our Western rangelands support some amazing animals. Many of which make impressive annual migrations, rivaling the famous movements of Wildebeest in the Serengeti and Caribou of the north. These populations possess a special ecological, cultural, and economic importance to communities across the U.S.

And while we’ve long known that these animals migrate, our understanding of the details is rapidly improving thanks to cutting edge technology, like GPS collars, and talented scientists at state game and fish agencies, the USGS, and universities. The more we learn, the more we understand just how essential private and tribally owned working lands are for these wildlife. They underpin almost every mapped migration route.

As part of the expansive team of partners supporting these migrating herds, Working Lands for Wildlife (WLFW) is proud to be part of the USDA’s commitment to support rancher driven, science informed and agency supported conservation efforts aimed at conserving these majestic migratory big game animals and the working lands upon which they depend. We have a long history of working with partners to deploy win-win solutions across millions of acres and are uniquely positioned to help conserve seasonal ranges of migratory big game where they intersect private and tribally owned working lands.

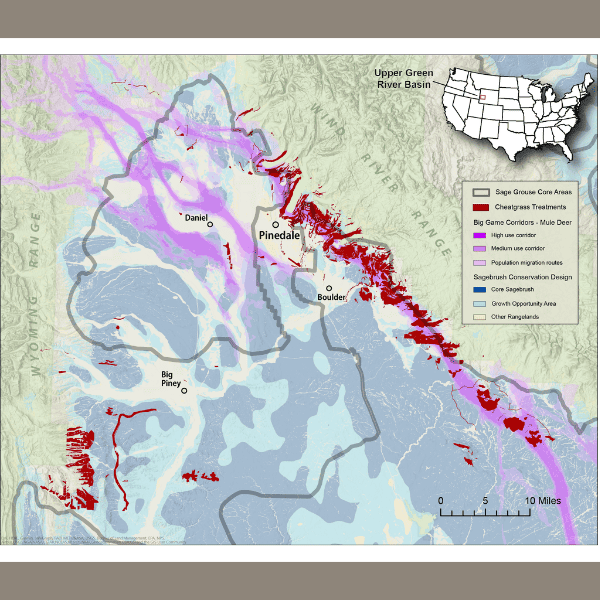

The potential of this opportunity was demonstrated through a pilot project in Wyoming over the past couple years. This project brought together the collective tools of the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Farm Service Agency (FSA) alongside those of the State of Wyoming and many other partners, resulting in many large-scale and tangible results:

- $11 million invested through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) resulted in 97 new contacts that conserved 307,713 acres. Most of these funds were used to remove unnecessary and/or non-wildlife friendly fencing, replace still-needed fencing with new wildlife-friendly fencing, and to treat invasive annual grasses.

- $8.3 million invested into the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) provided funding to establish seven conservation easements that now perpetually maintain 11,182 acres of working lands as open space available to migrating wildlife.

- A substantial increase in Grassland Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Ranchers in Wyoming responded to Grassland CRP opportunities in 2023 by increasing the number of offers in the signup by 30 percent when compared to the signup in 2022. Twenty-five percent of accepted offers in Wyoming for 2023 are in the big game corridor priority area (37,000 acres), up from 10 percent in 2022 (14,000 acres).

And we’re not stopping there.

USDA is determined to scale up this work and has recently announced a new ‘WLFW Migratory Big Game Initiative.’ This new Initiative, modeled after the popular Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI), provides dedicated funding to continue investing in Wyoming’s conservation efforts while also expanding in Montana and Idaho.

Just as we have done with SGI for more than a decade, WLFW is helping support this work through increased coordination and targeted investments in science, technical transfer, and communications. We also plan to develop a Framework for Conservation Action, akin to those we have in place for Sagebrush and Great Plains Grasslands, that will guide and focus our migratory big game actions across a much larger area of the West in the near future. We’ll share more details on that project when available.

I’d like to thank each and everyone of you for making working lands conservation a success!

~Tim Griffiths, NRCS Western Working Lands for Wildlife Coordinator

Initiative Expands to Three States

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE WYOMING PILOT AND EXPANSION TO MT AND ID

USDA’s Migratory Big Game Initiative provides a new package of investments in key conservation programs for fiscal year 2024, which includes funding to support increased staffing capacity and the deployment of streamlined program application processes for agricultural producers and landowners. For fiscal year 2024, NRCS has provided Wyoming, Montana and Idaho with $21.4 million in dedicated funding to kickstart the new Migratory Big Game Initiative.

USDA will offer producers a package of opportunities they can choose from to meet their operations’ unique needs. Programs include the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) and Grassland Conservation Reserve Program (Grassland CRP) and will be available across a wide range of lands including grasslands, shrublands, and forested habitats located on tribal and privately owned working lands.

U.S. Senate Holds Hearing on Wildlife Movement & Migration

SENATORS EXPRESS BROAD BI-PARTISAN SUPPORT FOR BIG GAME

On November 14, the Fisheries, Water and Wildlife subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works held a hearing called, “Challenges and Opportunities to Facilitate Wildlife Movement and Migration Corridors.”

In addition to the bi-partisan backing for efforts to conserve migratory wildlife expressed in the hearing, senators repeatedly expressed support for the voluntary, incentive-based conservation model WLFW promotes and for the integral role private working lands play in conserving the West’s unique populations of migratory big game species.

As this testimony shows, there is incredible support for this conservation effort. WLFW is excited to play a key role by working with private landowners, public land partners, and NGOs to conserve the resilient, working ranches so critical to the West’s wildlife and heritage.

Animal Trails: Rediscovering Grand Teton Migrations

FILM CELEBRATES BIG GAME MIGRATIONS AND CRITICAL CONNECTIONS BETWEEN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE LANDS

A new wildlife documentary chronicling the large mammal migrations of Grand Teton National Park highlights how the park is biologically connected to distant habitats in Idaho and Wyoming, many of which are working lands stewarded by multi-generational ranching families.

The film documents more than a decade of research revealing how Grand Teton National Park’s mule deer and pronghorn actually depend on habitats up to 190 miles away from the park boundaries.

Many of the wild animals that visitors enjoy in Grand Teton spend only part of the year there. Winter ranges and migration routes across Idaho, Wyoming, and the Wind River Indian Reservation are vital for the survival of big game herds in the national park.

“Grand Teton migrations are a story of diverse land ownership, and stewardship of migrations on this landscape over thousands of years,” said director Gregory Nickerson, a writer and filmmaker with the Wyoming Migration Initiative at the University of Wyoming.

Animal Trails was co-produced by the Wyoming Migration Initiative and Grand Teton National Park. The film is part of a new migration-themed exhibit Grand Migrations: Wildlife on the Move that recently opened at the park’s Craig Thomas Visitor Center in Moose, Wyoming. Both the film and exhibit reflect a growing emphasis by Grand Teton National Park managers to tell the story of wildlife migrations and the regional partnerships needed to conserve them.

Animations in the film show how mule deer make some of the most impressive migrations among ungulates, or hooved mammals. Some mule deer depart Grand Teton National Park to migrate west over the 9,000-foot passes into Idaho, where they spend winter along the Teton River Canyon and the wheat fields of the Teton Valley.

However, the majority of mule deer stay in Wyoming and migrate east across rugged mountain passes to the Shoshone River near Cody, the Wind River Indian Reservation, or the Green River Basin.

Maps of the migrations underscore how a significant part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem centers on migrations to Grand Teton National Park. More than a century of conservation has sustained these animal movements across national parks, national forests, Bureau of Land Management sites, and vast working lands (private ranches) that are a hallmark of the “Cowboy State.”

And yet, the biologists in the film recognize growing threats to Grand Teton migrations due to rural development, increased traffic, outdated fence designs, loss of working ranchlands, other private lands, and more.

In response, partners have joined together to conserve migrations and open spaces through public-private partnerships that cross jurisdictional boundaries.

Often migrations are anchored by private lands stewarded by ranchers and farmers, many of whom voluntarily place their lands in conservation easements. Some of these very landowners helped create nonprofits like the Jackson Hole Land Trust, the Wyoming Stockgrowers Land Trust, The Nature Conservancy, Teton Valley Land Trust, and others.

The film has a runtime of 25 minutes and will screen at the Grand Teton National Park Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center and Colter Bay Museum during the summer 2024 season.

Note: This text is adapted from the Grand Teton National Park press release announcing the film.

The following success stories highlight efforts related to the Wyoming Big Game Initiative pilot program, which launched in 2022 and has now expanded to Idaho and Montana.

New Partnership in Wyoming Rewards Landowners for Stewarding Wildlife Habitat

Across America, wildlife depends on habitat provided by private working lands. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, a sprawling landscape of public, private and tribal lands around Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, was the perfect place to pioneer a locally led model that rewards the landowners there who are stewarding our treasured natural resources.

This story shares some more information about the Wyoming Big Game Conservation Pilot program that now includes Idaho and Montana.

Saving Time, Money and Wildlife through Conservation Practices

When Jeff Boardman took over his family’s Wyoming ranch in 2015, he quickly realized the benefits of working with the NRCS. Most recently, Boardman rebuilt old fencing with wildlife-friendlier fencing that keeps his cattle in and helps facilitate wildlife movements across his ranch.

Boardman is definitely a fan. Although he thought the wildlife-friendly fence design was “kind of goofy looking at first,” he’s been impressed with how well they hold in his cattle. In fact, Boardman plans to use the same design when replacing more fences on his ranch in the coming year.

Making Fences Friendlier for Ranchers and Wildlife

“We’ve got all the good stuff—elk, moose, antelope and sage grouse. Plus, we’re in the middle of the biggest mule deer migration corridor there is,” says Mike Vickrey, a fifth-generation rancher in Pinedale, Wyoming. His family’s desire to help the local wildlife led Vickrey to seize the opportunity when the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) began offering to help improve fences through its Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP).

Through the partnership, Vickrey has modified six miles of fence through EQIP in places where big game migrate each spring and winter. He’s also flagged fences with reflective markers in partnership with NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife to prevent sage grouse from getting tangled in the wires when they fly low to the ground. These fences still work well to keep cows contained, too. So far, Vickrey says he hasn’t found any wildlife hung up on his new fences, and they also keep his livestock where he wants them. He’s now partnering with the U.S. Forest Service to modify fences on public land where his family leases grazing allotments and the “elk are thick, thick, thick.”