Holding the Line: Defending Wyoming’s Sagebrush Cores from Cheatgrass

Sublette County, Wyoming has successfully treated more than 97,000 acres of cheatgrass, protecting core sagebrush habitat.

WLFW Attends National Pheasant Fest and Quail Classic

March 21, 2024

Where Trees Are the Problem

April 10, 2024The Sublette County Success Story

By Nell Smith and Greg M. Peters

After a long hard winter, the south-facing slope above Boulder Lake in Sublette County, Wyoming is lush. Needle and thread grass sways thigh-high and big bunches of arrowleaf balsamroot bloom in punches of yellow. Intermixed among the many large rocks are a host of other wildflowers and grasses.

Notably absent among these native species, is cheatgrass. This lack of cheatgrass is no lucky accident. It is the result of Sublette County’s proactive treatment program—one of the first success stories in treating cheatgrass at a landscape scale.

The road to this point hasn’t been easy, but as Julie Kraft, Sublette County’s Weed & Pest Supervisor, looks across the slopes of Boulder Lake today, her eyes brighten. “When we see results like this, along the scale of thousands of acres, it’s like, man, I’m glad that we didn’t give up.”

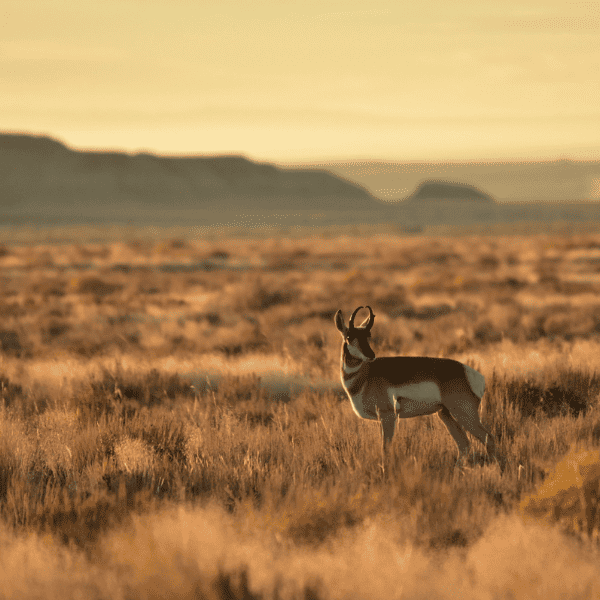

Located at the head of the Upper Green River Basin, 3.2-million-acre Sublette County is comprised of vast sagebrush rangelands interspersed with verdant valley bottoms and flanked on three sides by large mountain ranges. Such diverse and intact habitats, stretched across over a mile of elevation change, create a wildlife mecca.

Migratory big game like pronghorn and mule deer take centuries-old paths between their ancestral seasonal ranges in what are some of the longest documented ungulate migration corridors in North America. It is also home to some of the most productive core habitat for species that rely on intact sagebrush rangelands. In fact, some might call it the ‘core of the core’ since more than 40% of all the sage grouse on earth live in Wyoming, and 40% of those birds reside in Sublette County.

Sublette County’s lower elevation sage-steppe is part of the Wyoming Basin, the largest intact sagebrush ecoregion in North America. Keeping these rangelands healthy, resilient, and functioning is critical to wildlife and people. While Sublette County, and the broader Wyoming Basin, house some of the last remaining intact sagebrush grasslands and shrublands, invasive annual grasses, including cheatgrass, are threatening the region’s ecological integrity.

According to the Sagebrush Conservation Design, a multi-agency report and conservation framework, 1.3 million acres per year of intact sagebrush rangelands are being degraded by large-scale threats like invasive annual grasses, conifer encroachment, wildfire, and development across the West’s sagebrush biome – a 175-million-acre area that stretches from New Mexico to southern Canada. Furthermore, invasive annual grasses are responsible for nearly 69% of the degradation.

Not on My Watch

When Kraft first moved to Sublette County in 2010 to join the County’s Weed & Pest team, she wasn’t thinking about cheatgrass. But in one of her first meetings with the local sage grouse working group, the question was raised—did Sublette County have cheatgrass? And, if it did, what was Weed & Pest going to do about it?

At that point, Kraft had been living in the county for a matter of weeks. She didn’t know the names of all the places people were referencing, let alone whether they had cheatgrass. But she knew about the problems it was wreaking in the Great Basin. She had seen it spread to high elevations, despite the assumption at the time that it wouldn’t. Mostly she knew she needed to find out more and she needed partners.

In short order, Kraft teamed up with folks from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, USDA-NRCS, and others, and they got to work.

First, the group of resource managers invited anyone from the community who had information on cheatgrass, or who were simply interested in learning more, to an open house. Folks from the energy companies brought in location data. Private landowners pointed to where they’d seen it growing on their land. Other members of the community shared memories of where they’d seen it. In time, the team was able to compile these disparate bits of data into a map that provided a starting point.

Sublette County, like many western counties, includes a mix of public and private lands, and Kraft knew the team needed to work across these boundaries if they stood a chance of success. She also knew they would need to learn how to treat infestations most effectively. So, the team expanded to include individuals from state and federal agencies, the county conservation district, universities, energy companies, and private landowners.

Engaging with the community through open houses and establishing a task force with the right partners were crucial first steps, and the team soon shifted to on-the-ground action. Their early efforts focused on ground-truthing the community-sourced data and on fundraising.

Remote-sensing products that can detect grasses from space weren’t yet available, so the team spent time, and money, driving, walking and flying all over the county, refining the community’s input and finding as-yet-undetected infestations. They started on roads because they were easy to navigate and were known by the community to harbor cheatgrass. They also focused their surveys on warmer, south-facing slopes where the harsh conditions on these sites were more conducive to the annual grass.

Parallel to their surveying efforts, they teamed up with herbicide industry experts and research partners at the University of Wyoming to establish small study plots, so they could test different herbicide treatments and learn what worked best for the specific soils and climate of Sublette County.

Strategic use of skills and expertise allowed the still small team to move quickly and deftly while reinforcing the power of strong partnerships. Egos and baggage “were checked at the door,” says Kraft.

With grant money for implementation starting to come in, an initial understanding of where cheatgrass existed on the landscape, and study plots and research partners in place, it was time to start fighting back. Navigating the complexities of management requirements on public lands proved an early challenge, but the team found an ally in DeWitt Morris, an active and influential local rancher with a penchant for sage grouse. Morris offered the group an opportunity to treat his acreage with herbicide that targeted the invading grass.

Morris’ early buy-in proved pivotal, not only in starting treatment on the ground but in creating more awareness and interest from other landowners. Kraft says Morris helped the team garner trust and credibility with neighboring landowners. “Hey, it worked on my side and can work on your side.” And because they had included treatments on all the different land ownerships into their grant applications, they were able to build in the flexibility to take advantage of opportunities to collaborate like this across private and public lands.

Photo: Julie Kraft.

Photo: Julie Kraft

Kraft also got cheatgrass listed on Sublette County’s noxious weeds list in 2015. This seemingly small move proved a strategic masterstroke for garnering additional grant monies and streamlining treatment tactics on non-federal lands. Their survey work showed that most of the infestations ran along the south- and west-facing foothills of the Wind River Range and, to a lesser degree, along the foothills of the Wyoming Range.

Infestations were also clustered around roads – known conduits for all kinds of invading species – and so the team started treating cheatgrass along roadsides. Critically, the survey effort also revealed where cheatgrass wasn’t. To the west of this line, much of the county’s high-value core areas remained intact and relatively cheatgrass-free.

Kraft and the team recognized that preventing these intact cores from becoming invaded represented the best chance for maintaining their ecological integrity. To do that, the team deployed a “Hold the Line” strategy to try to keep cheatgrass from marching out of the foothills and into the valley’s intact cores. This watershed-scale, proactive approach to managing cheatgrass preceded, and foreshadowed, the current “Defend the Core, Grow the Core” approach that has emerged as the battle cry throughout the West.

A New Tool Emerges

As Kraft and the team evaluated treatment prescriptions, implemented public education efforts about cheatgrass and other invasive weeds, and treated roadways and other hotspots, a new herbicide emerged in the battle against invasive annual grasses: indaziflam.

When first released for annual grass control, indaziflam (trade name, Rejuvra) wasn’t approved for application on lands actively grazed by livestock. However, in 2016, the team began testing it on ungrazed lands along the flanks of Boulder Lake, which lies on the Bridger-Teton National Forest. To really understand its potential, they collaborated with Colorado State University scientists to conduct a five-year experiment evaluating treatment efficacy.

Then, on August 17, 2019, a wildfire broke out on the slopes above Boulder Lake. It was a windy day during a dry year. Once the fire hit the ridge, it blew across the whole mountain. “I remember the day and exactly what I felt. I was in tears,” recalls Kraft. Unbeknownst to Kraft and her team, the wildfire would provide a natural and much needed experiment testing the efficacy of this new treatment option.

The Boulder Lake Fire burned nearly all the slopes where the team had treatment plots. “At first glance, everything was just ash and black and gone,” Kraft remembers. But as partners set out to assess the damage, they noticed that the fire had burned unevenly across the slope. The fire, they realized, provided an unexpected chance to observe how fire behavior responded to treatment areas. And what they were seeing on the ground were patches of sagebrush that the fire hadn’t burned through, right where they had treated.

Julie remembers it as a roller coaster of emotions. While it wasn’t great and wasn’t planned, she realized that where indaziflam had cleared cheatgrass, the fire didn’t have fuel to burn, and it simply moved past and around their treatment plots. What they were setting out to do, in other words, was working. “It was,” she says, “very exciting.”

The team’s treatments killed the cheatgrass, which eliminated the fine fuels that help fire spread between native bunchgrasses and shrubs. Now, nearly four years later, native species are prolific along the slope and are interspersed with the bare patches of glacial till that naturally occur when cheatgrass doesn’t choke it out. Snowberry and sprouting bitterbrush dot the hillsides, and a peppering of pink bitterroot flowers and a scattering of fringed sage adorn the ridge tops.

The key according to Kraft? Treat cheatgrass early and proactively, while there are still sufficient native species on the landscape.

“We are seeing these sites recover,” Kraft says. “Our native rangelands are resilient. Once we give it a little help, nature can heal itself.”

And the team now has the science to back up their field observations. Published findings out of Colorado State University show that indaziflam provided cheatgrass control for five years following treatment with no impact on perennial grasses. In some instances, cheatgrass appeared to be eliminated from the plots entirely.

In 2020, indaziflam gained approval for application on grazed lands under the trade name Rejuvra, opening the door to more widespread use for treating invasive annual grasses across the western U.S. The Sublette team quickly adopted this new technology, incorporating it into their treatment prescriptions. In some areas, like Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands, the team continues to use imazapic while land management agencies work through approval processes to add indaziflam to their toolbox.

Hope on the Slope

Today, nearly a decade after that first open house and years after they started treating cheatgrass along roadsides and south-facing slopes, the team has treated nearly every known area of cheatgrass in Sublette County – over 97,000 acres. Despite numerous challenges and setbacks, Kraft and her team of partners have worked across private and public land boundaries to successfully defend their valuable, intact sagebrush rangelands from further cheatgrass invasion.

Out on the range, native plant species are thriving and, so far, the cheatgrass isn’t coming back. “Year after year after year, there’s still no cheatgrass in those sites. Those sites are still clean.” Kraft is careful to acknowledge the unknowns—how long exactly will the control persist? How often will they need to re-treat? But she is cautiously optimistic.

Their experimentation with different herbicide applications, methodical tracking of results, commitment to treating areas multiple times, and their “Hold the Line” approach is producing positive long-term outcomes. Yes, treated areas are largely cheatgrass free, but perhaps more importantly, the core areas where cheatgrass never existed also remain cheatgrass free. Even still, the team is vigilant, conducting extensive annual monitoring to evaluate past treatments, locate new infestations, and devise plans for treatments as needed.

Land managers across the West are better equipped to strategically tackle invasive grasses today than when the Sublette team got started with the availability new tools like improved herbicides and remotely sensed vegetation maps, as well as technical resources and support. The University of Wyoming’s Institute for Managing Annual Grasses Invading Natural Ecosystems (IMAGINE) is leveraging the hard-won lessons learned by the Sublette team and sharing technical know-how, strategies, and resources to empower land managers to defend and grow their sagebrush cores through an interagency technical transfer partnership.

Proactively protecting remaining core sagebrush areas, like that found in Sublette County, from becoming invaded is a key tenant of conservation strategies embodied in the Sagebrush Conservation Design and NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife’s Framework for Conservation Action in the Sagebrush Biome. Alignment of these strategies with new funding from the Inflation Reduction Act, through the Farm Bill, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and state-based funding enable land managers to implement cheatgrass management at meaningful scales.

What Kraft wants to stress now, is that if “you’re asking the question—should I be doing cheatgrass work or invasive annual grass work? Then it probably is important enough and you should get started. And you need to hurry.” Make a plan. Start the process. “It actually can come together a lot quicker than you think.”

Partner acknowledgements: Sublette County Weed and Pest, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Bureau of Land Management, Bridger Teton National Forest, Sublette County Conservation District, Sublette County Invasive Species Task Force members, University of Wyoming IMAGINE. So many funding sources big and small! A special thanks to Karen Clause, Jennifer Hayward, Jill Randall, Troy Fieseler, Jake Courkamp, Brian Mealor, Chad Hayward and Kelsey Smith.