PHEASANTS FOREVER Magazine | Of Partners, Promises and Prairie Treasures

Magazine Story | Pheasants Forever’s Spring 2020 Journal of Upland Conservation features how the nonprofit works with SGI and other partners to benefit a variety of grouse species including sage grouse and lesser prairie-chickens. Read the magazine stories now. Reposted with permission.

PHEASANTS FOREVER Magazine | Of Partners, Promises and Prairie Treasures – LPCI

February 13, 2020

Ask an Expert | How Does Grazing Affect Native Pollinators

February 20, 2020

Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever have been long-standing partners of the Sage Grouse Initiative, the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative and other Working Lands for Wildlife initiatives across the country. The organizations are best known for their work on pheasants and quail but their support for other upland bird species and for wildlife in general is making a real difference for wildlife not typically associated with the organizations.

In particular, Pheasant Forever’s support of the Sage Grouse Initiative and the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative has helped build out our Strategic Watershed Action Team (SWAT) who work on the ground with local ranchers, producers and NRCS staff to help implement SGI and LPCI conservation practices. Learn more about how PF supports SGI and LPCI here.

The Spring 2020 edition of Pheasant Forever’s Journal of Upland Conservation features four stories about North American grouse and how PF is partnering with groups and agencies like the USDA-NRCS to improve habitat for sage grouse, lesser prairie-chickens, greater prairie-chickens and Columbia sharp-tailed grouse. The sage grouse and lesser prairie-chicken excerpts are reposted here with permission.

>>Download a PDF of the magazine story here<<

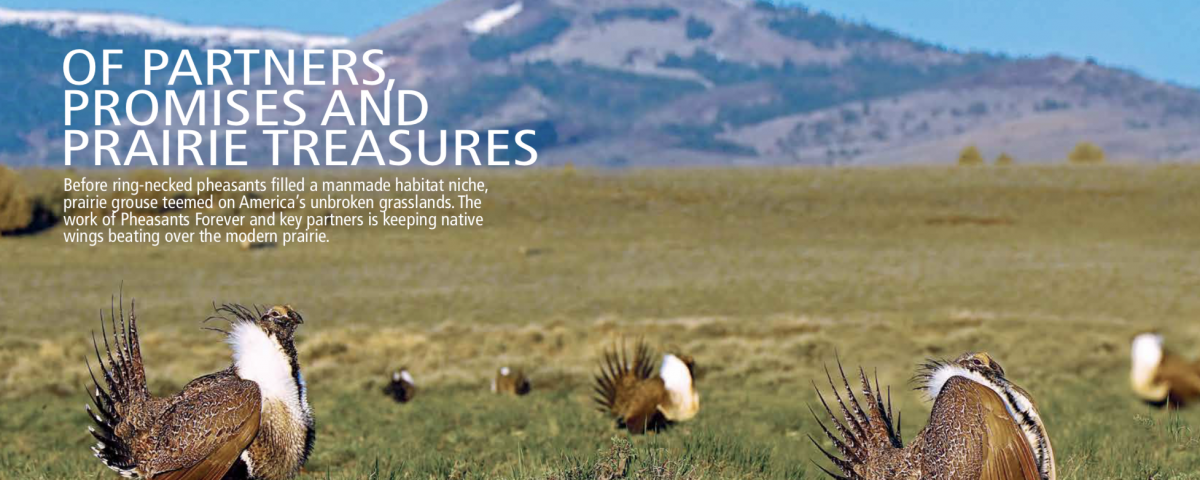

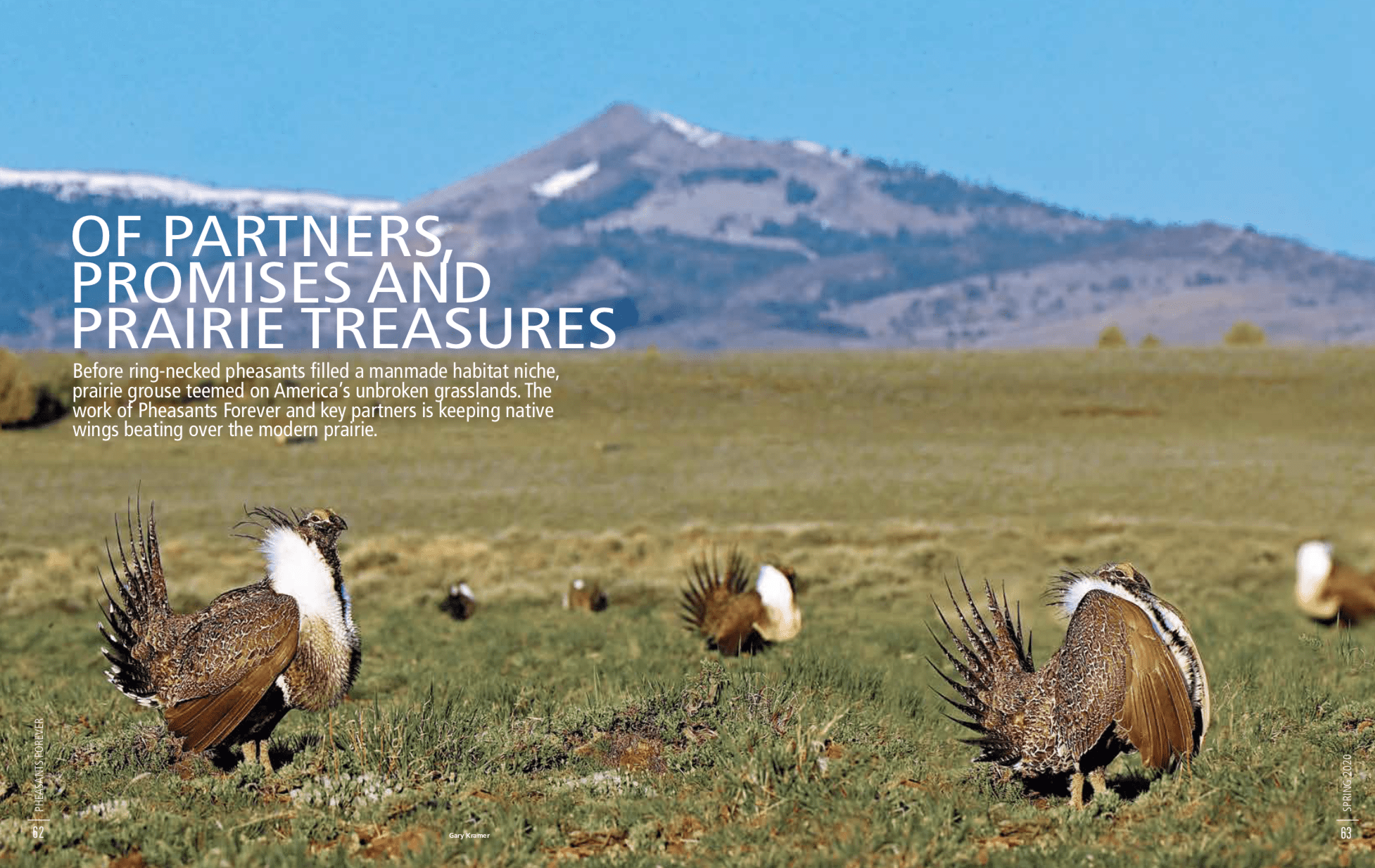

Photo by Gary Kramer.

Sage Grouse: A Shared Vision of a Resilient West

By: Brianna Randall

Sunset drapes across the wide-open western range, tinting the snow-covered sagebrush pink. The fading light silhouettes a herd of elk against distant peaks, while the call of cattle echoes over the whistling wind. If you zoom in closer, you’ll spy coveys of football-sized birds beneath the sagebrush, eating the silvery-green leaves and staying warm during the harsh winter.

These are sage grouse, North America’s largest grouse. And this scene is taking place in any one of a dozen states in the western U.S. this winter on rangeland treasured by bird hunters.

As the snow starts to melt, sage grouse herald spring by congregating to mate in open areas called leks. Males strut and prance, inflate yellow air sacs on their white chests to make a champagne-cork pop, and fan their spiky tail feathers to entice nearby females. Some leks boast hundreds of birds. It’s an impressive natural spectacle for those lucky enough to witness it.

Sage grouse might be most famous for their quirky courtship dance. But they’ve also become known as an indicator for how their namesake ecosystem is faring.

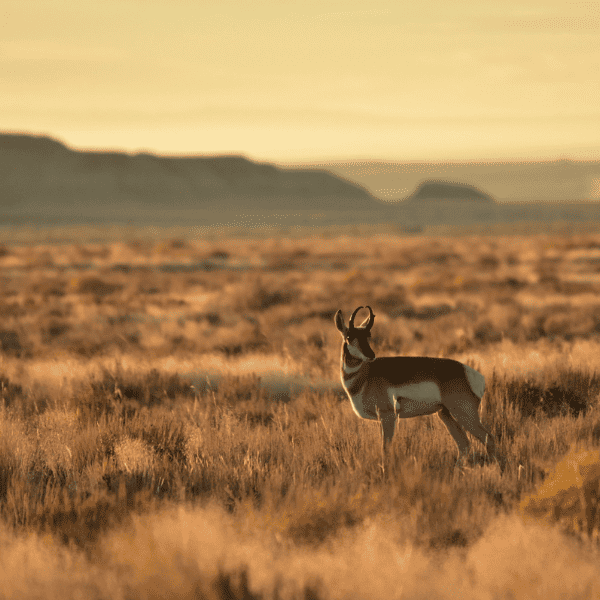

Characterized by a diversity of shrubs, grasses and flowering plants, the sagebrush steppe covers 250,000 square miles and is home to 350 species, including pygmy rabbits, pronghorn, mule deer, elk, and golden eagles. Sage grouse are considered an “umbrella species” for all of the flora and fauna in this beautiful country because these upland birds rely entirely on sagebrush-dominated landscapes to eat, mate, hide from predators, and raise their chicks.

Over 100 sage grouse congregate on a lek in Colorado to mate. Photo: Julio Mulero

In short, without healthy sagebrush habitat there would be no sage grouse. And for a while, it was a close call for the birds.

Sage grouse have dwindled to a mere 10 percent of their historic numbers due primarily to substantial habitat loss. Over the past century, the sagebrush sea has been chopped up by invasive weeds, roads, energy or housing developments, and cultivated croplands. Sage grouse haven’t adapted well to these human-generated intrusions, since the birds avoid roads, tall structures, and loud noises.

The bird’s decline led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to determine in 2010 that greater sage-grouse were warranted for listing under the Endangered Species Act, with a final decision on whether to list the bird due by 2015.

Sage Grouse Initiative

Immediately following that announcement, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) launched the Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI) to proactively conserve the private land where sage grouse roam. Ranchers, industry leaders, nonprofit organizations, and local, state and federal government agencies formed an unprecedented coalition to voluntarily conserve sagebrush rangelands. This coordinated effort was primarily motivated by the concern that listing the sage grouse would disrupt a host of economic mainstays that rely on the sagebrush ecosystem—including hunting.

Over half of the remaining sage grouse habitat is privately owned, much of it as working agricultural lands. Recognizing that “what’s good for the bird is good for the herd,” SGI focuses existing Farm Bill programs to help ranchers put in place sustainable ranching practices that conserve wildlife habitat while also benefiting their agricultural operations.

From the outset, Pheasants Forever has been a key partner with NRCS for efficiently converting SGI-allotted Farm Bill dollars into improved habitat for sage grouse.

“Our ethos has long been that working in harmony with agricultural producers to maintain healthy habitat is what supports healthy upland bird populations on a landscape level. With SGI, we saw an opportunity to help the NRCS—as well as ranchers and bird hunters in the West—with a habitat conservation paradigm that invites collaboration instead of conflict,” says Howard Vincent, president and CEO of Pheasants Forever & Quail Forever.

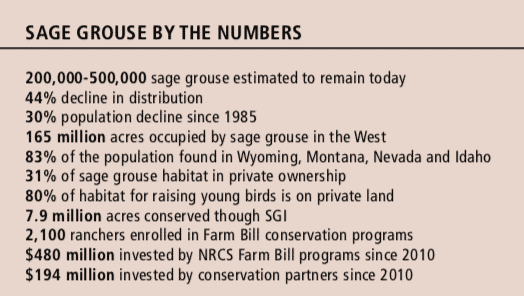

That paradigm has proven its worth and then some. Over the past decade, SGI has partnered with more than 2,100 ranchers to conserve nearly 8 million acres of sagebrush rangelands in core sage grouse habitat—an area three-and-a-half times the size of Yellowstone National Park.

“Our role is to help NRCS and other partners deliver conservation dollars, contracts, and field capacity as efficiently as possible, so that grouse get the best bang for the buck,” says Ron Leathers, a wildlife biologist who also serves as Pheasants Forever’s director of public finance and has been involved with SGI since its inception.

Farm Bill Biologists

Leathers points to PF’s investment in hiring and managing biologists across sage grouse range as one example of the organization’s long-term commitment to improving habitat. PF employs more than 185 Farm Bill biologists across the country who work with landowners to protect and restore wildlife habitat, and 20 of these biologists are based in sagebrush country. Many of these positions are cost-shared by the NRCS, state wildlife agencies, or other nonprofits.

“Our field biologists are local ‘boots on the ground’ who can help rural farmers and ranchers plan conservation projects that boost their agricultural operations while also improving wildlife habitat,” says Michael Brown, the SGI field capacity coordinator for Pheasants Forever.

These local field staff help put in place habitat improvement projects ranging from sustainable grazing systems, to marking barbed-wire fences to prevent bird collisions, to conservation easements.

SGI and LPCI SWAT staff gather in Idaho to learn about low-tech stream restoration techniques. PF cost-shares most of these positions, providing additional capacity and getting more done on the ground. Photo: Greg M. Peters

Conservation Easements

Habitat loss through development is the most irreversible threat to sage grouse. Conservation easements are an important tool for keeping sagebrush rangeland intact. In Wyoming, estimates show that a $250 million investment in targeted easements can slow grouse declines by nearly two-thirds within population strongholds.

Through NRCS Farm Bill programs, partners have now secured over 200 individual easements that permanently conserve 620,000 acres of working western ranchlands. In Montana alone, partners have protected 198,000 acres of at-risk range through SGI since 2010, a six-fold increase in easements over all years prior. These voluntary, incentive-based agreements with private landowners also maintain working ranches and keep this vast landscape whole for future generations.

Grazing Smart

In addition to permanently protecting land from development, SGI has also helped ranchers improve range health across 3.6 million acres of prime sagebrush habitat through sustainable grazing strategies. By working with individual landowners to adjust the timing, intensity, and duration of livestock use, grazing strategies promote diverse, native plant communities that provide food and shelter for grouse and other animals. This makes the land more resilient to drought and wildfires, and increases its productivity for livestock, too.

“SGI’s win-win approach provides solutions that are good for ranchers and good for grouse,” says Tim Griffiths, the western coordinator for NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife, which includes SGI. “That means we’re not only working to improve wildlife habitat, we’re also helping to sustain rural communities and maintain our way of life out West.”

Eliminating Woody Cover

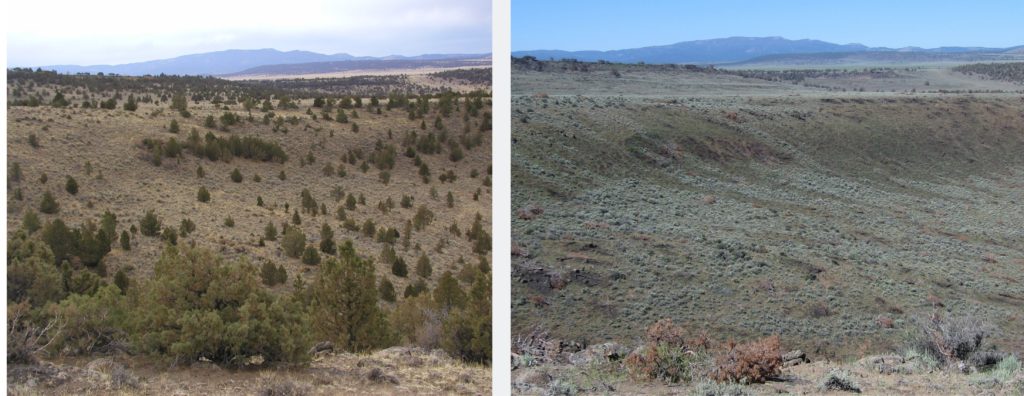

Another big threat to sage grouse is the encroachment of woody species. Typically found in higher-elevation forested areas, trees like juniper have steadily marched across historically open sagebrush range over the past century due to fire suppression efforts.

Sage grouse hate trees and research shows that they avoid nesting in areas where there’s more than a single tree per acre. Invading trees provide perches for predators like raptors, and also crowd out the native low-to-the ground plants and shrubs that sage grouse prefer for brooding, nesting and chick-rearing.

SGI has helped landowners strategically remove encroaching trees to restore over a half-million acres of sagebrush habitat. Projects on private lands are often paired with complementary conifer removal work on adjacent federal- or state-owned land, which restores big chunks of habitat to health—to the advantage of everyone who values clean water, healthy soils, and open horizons.

In Oregon, conifer removal boosted sage grouse populations by 12% compared to areas where no conifer removal occurred. Photo: Todd Forbes.

“Sage grouse don’t stop at fences, so we try to work across entire watersheds by including multiple property owners in conservation actions,” explains Brown. “At the end of the day, what’s most important is to build resilient, functioning landscapes that also work for agricultural families.”

The science indicates that this watershed-scale conservation is working. For instance, research shows that in southern Oregon, sage grouse populations were 12% higher in areas where advancing trees had been removed. Plus, 29% of GPS-tagged sage grouse hens were nesting in or near restored sagebrush rangelands within three years of conifer treatments.

Water is Critical

Speaking of nests, research also shows that sage grouse cluster 85% of their breeding sites within 6 miles of wet habitats in order for hens and chicks to feed on the “green groceries” found near water. As the sagebrush uplands dry out in the late summer, the birds seek out protein-rich plants and insects found along streams, springs, and wet meadows. More than 80% of vital wet places in the West are located on privately owned ranchlands; but many of them are degraded.

SGI helps resource managers and landowners use simple, cost-effective methods that restore these precious wet habitats. NRCS, PF, and other partners have led 11 hands-on field workshops that trained over 400 people in low-tech methods of restoring wet habitat (such as hand-built stone structures, mimicking beaver dams, or grazing management). Once implemented, these restoration projects have been proven to increase vegetation productivity by up to 25% and keep riparian areas greener longer. That’s another win-win for grouse and ranchers.

Big Country, Bigger Vision

All of these habitat improvements stem from one source: a shared vision of wildlife conservation through sustainable ranching. This vision, endorsed and practiced by Pheasants Forever and its partners, is undoubtedly working to revitalize sage grouse populations: In September 2015, the USFWS announced that sage grouse no longer warranted listing under the Endangered Species Act.

This positive news didn’t spur conservation partners to close shop though.

Instead, PF has partnered with NRCS to scale up the sage grouse model to benefit other at-risk animals. Working Lands for Wildlife—the umbrella for SGI—now allocates Farm Bill resources to conserve 23 other keystone species and their habitats across 48 states. Partnership-based efforts are enhancing private farms, forests and ranches from coast to coast, and are being replicated globally, too. Through Working Lands for Wildlife, PF is now involved in 9 landscape-scale conservation initiatives across the country, including bolstering habitat for prairie chickens and bobwhite quail.

“We’re in this for the long term,” says Howard Vincent, president & CEO of Pheasants Forever. “It’s about more than saving birds. It’s about saving the beautiful wide-open spaces that define America.”

Lesser Prairie Chickens: Places for Grouse on the Southern Great Plains

By: Brianna Randall

It’s dawn on the prairie, and the grass-scented spring air is alive with birdsong and butterflies. Rocky red buttes rise through the undulating waves of green, while tall oaks shade winding streams. These are America’s Great Plains, which cover one-third of the country and support grazing animals, burrowing critters, and millions of birds.

As the sun peeks over the grass on a mild spring morning, bubbling sounds ring across the land—the lesser prairie chickens are “booming.” Males with dashing yellow eyebrows call in the plainer brown-and-white-striped females by inflating balloon-like red pouches on their necks. These grouse also stomp their feet, flutter-jump, and lunge in hopes of luring in one of the hens. Alas, the ladies are picky: they often visit two or three dancing grounds before selecting their mate.

Lesser prairie-chickens. Photo by Nick Richter.

Diminishing Habitat

Similar to sage grouse, this once-popular game bird used to number in the millions, booming on leks across our nation’s southern prairies. But this quirky chicken-like bird has declined precipitously due to dwindling habitat.

Only an estimated 38,000 birds remain.

The Great Plains are some of the most at-risk landscapes on our continent, threatened by conversion of native grassland to cultivated farmland, invasive weeds, and encroaching woody species. Because much of their native habitat has disappeared, the lesser prairie chicken now occupies just 17 percent of its original range. Today, this upland bird is found in portions of Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas, where short- to mid-grass prairie is dominated by shinnery oak and sand sagebrush.

Prairie in New Mexico. Photo: Andy Lawrence

Private Lands Key

Over 95 percent of the land in the southern Great Plains is owned by farmers and ranchers—the economic mainstays for hundreds of rural communities. With nearly all of its habitat under private ownership, conserving the lesser prairie chicken for future generations depends on voluntary actions by private landowners.

Pheasants Forever is partnering with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), local conservation groups, and state resource agencies to work with landowners on putting into place practices that are mutually beneficial for these birds and for agricultural producers alike. Farm Bill biologists, cost-shared by PF, offer ranchers the technical know-how for creating more productive and resilient grasslands.

“The range of the lesser prairie chicken overlaps with several species of quail and pheasants, so our work to restore prairie grasslands helps a whole host of upland birds,” says Jordan Menge, lesser prairie chicken coordinator for Pheasants Forever & Quail Forever.

Lesser Prairie Chicken Initiative

Historically, natural disturbances such as frequent wildfires and grazing by bison herds helped maintain healthy prairie habitat. The removal of these large-scale forces from the Great Plains has led to a shift from grasslands to woodlands, which diminishes the productivity of the prairie for both wildlife and livestock.

This lesser prairie-chicken is feeding on grasslands that were burned by a prescribed fire. Fire played an integral role in maintaining grasslands health historically and today, prescribed fire is used to achieve the same goals. Photo: NRCS.

Sustainable ranching activities can help deter invasive annual grasses (like cheatgrass) or woody plants (like redcedar or juniper) from taking over native prairie … and crowding out grouse.

Pheasants Forever is a key partner in the Lesser Prairie Chicken Initiative (LPCI), led by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. LPCI works with ranchers to restore large blocks of prairie in the Southern Great Plains by: reintroducing fire to the landscape; rotating the timing and duration of livestock grazing to conserve native vegetation; and installing a host of other sustainable ranching practices.

CRP Matters

Pheasants Forever also helps broaden landowner participation in USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which pays landowners to replant native vegetation on former crop lands to restore grasslands.

“Pheasants Forever has been a staunch advocate of USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program since its inception in 1985 because it helps us enact our mission to conserve upland bird populations through habitat improvements,” says Howard Vincent, president and CEO of Pheasants Forever & Quail Forever.

A new study released from Bird Conservancy of the Rockies shows that these voluntary Farm Bill-funded programs do indeed work, and produce outcomes that matter. Lands enrolled in CRP or prescribed grazing programs produced 3 million more birds in the southern Great Plains, boosting populations of 24 species of grassland birds, 17 of which are in decline.

Workshops and Tools

Pheasants Forever partners with NRCS and others to share research results like these in order to bridge the gap between science and on-the-ground implementation. That means hosting workshops that share the most recent research with ranchers and land managers so they can more effectively conserve habitat.

It also means creating easy-to-use tools (like the free online mapping application at rangelands.app) that allow people to track changes in natural resources over time. These science-based tools help partners quickly measure the results of past conservation work and plan future projects.

“Our goal is to measure the big-picture scientific outcomes from investing Farm Bill dollars to ensure conservation practices are successful and cost-efficient,” says Dr. David Naugle, science advisor for NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife, which includes the Lesser Prairie Chicken Initiative. “This science-based approach allows us to provide the biggest benefits for people and wildlife.”