Ask an Expert | How Does Grazing Affect Native Pollinators

Join Gabrielle Blanchette for a deep dive into the role native pollinators play in rangelands and how grazing can impact these critical components of a healthy ecosystem.

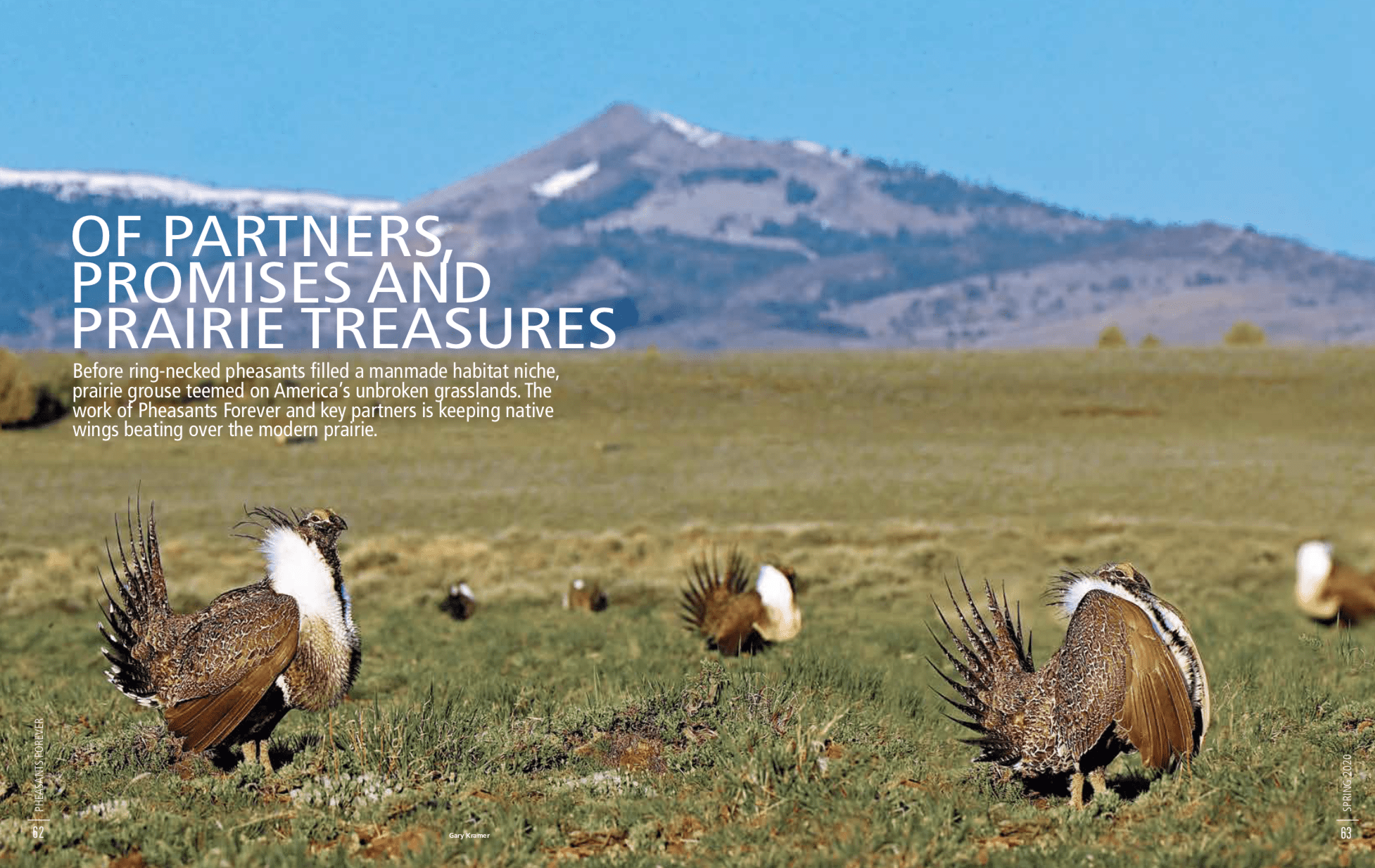

PHEASANTS FOREVER Magazine | Of Partners, Promises and Prairie Treasures

February 13, 2020

Ask an Expert | When it comes to sage grouse habitat: Don’t sweat the small stuff

February 27, 2020

Monarch butterflies are one of the best known pollinators. Photo: Jim Hudgins, USFWS.

One understudied, but critically important, component of the sagebrush ecosystem is the role that native pollinators play in maintaining the health and diversity of plants and animals throughout the sagebrush sea.

Pollinators, insects, birds, and animals that transfer pollen from one plant to another as part of the plant’s lifecycle and reproductive strategy, play an outsized role in maintaining the biodiversity and function of particular plant groups in the sagebrush sea. Insects are especially important as they perform 85% of pollination services. Native bees, in particular, are critical to maintaining native plant species – they are responsible for 80% of flowering plant pollination. Globally, between $235 and $557 billion worth of food supplies rely on pollination services of some kind.

Wildflowers, like these found in wetter sites throughout sagebrush rangelands, rely on pollinators to reproduce. Photo: Jeremy Maestas.

Studying the role pollinating insects play in the sagebrush sea is important for several reasons. Most obvious, without pollination by insects, many plant species would simply disappear, which would be disastrous for a host of reasons. Wildlife like sage grouse, elk, mule deer, pronghorn and even grizzly bears and coyotes rely on pollinated plants (including forbs, fruits, seeds, and berries) for food, cover, and shelter resources. Many forbs also help fix nitrogen in soils, which helps other plants grow.

Birds, in particular, regularly consume insects, including pollinators. In fact, 61% of birds that breed in U.S. are insectivorous, another 25% are partially insectivorous. Arthropods (invertebrates that includes insects, butterflies, spiders, and even crabs and lobsters) make up more than 60% of sage grouse chicks’ diets in the first four weeks of their life, a critical stage for young birds. Recent research showed that sagebrush rangelands with managed cattle grazing had a higher abundance of the arthropods that sage grouse chicks eat than lands without cattle grazing.

In short, pollinators are fundamental to the health and biodiversity of sagebrush rangelands. Since much of the sagebrush landscape in the western U.S. is utilized for cattle grazing, studying the impact grazing has on native pollinators will help land managers and landowners better conserve sagebrush ecosystems.

A new study from Montana State University (funded in part by the NRCS’s Conservation Effects Assessment Project – Wildlife) looked into this very topic. We sat down with the study author, Gabrielle Blanchette, to chat through the study and its implications for sagebrush management.

Pollinators are likely something most of our readers know a bit about, but will you explain the roles they play in sagebrush ecosystems? What are they? What do they do?

In this study, we focused on primary pollinators, which are native bees, and also on secondary pollinators, which include flies from the Family Syrphidae, butterflies, and moths. These pollinators are important to sagebrush ecosystems for several reasons. The most important is simply that they pollinate nearly all of the flowering plant species that include forbs, succulents, and shrubs. These plants, in turn, prevent soils from eroding and contribute to healthy soils, while also providing habitat or forage for other wildlife. However, pollinators’ role in an ecosystem goes beyond pollination as they also serve as a major food source for many songbirds, grouse, and other insects.

What motivated or inspired you to study the relationship between cattle grazing and pollinators?

Grazing has long been a part of the western U.S., whether bison grazing millennia ago or more recently, domestic livestock grazing. Pollinator populations are dropping across North America, and the rusty patched bumble bee, was recently listed on the Endangered Species List. The first goal of my study was to catalog bees down to Genera in an area of Montana where they hadn’t been previously sampled. The second goal was to produce science that could be used to help guide on-the-ground conservation and decisions that benefit these critical parts of the sagebrush ecosystem as part of a proactive solution.

The rusty patched bumble bee. Photo: Kim Mitchell, USFWS.

Will you explain how you set up your study near Roundup, Montana and what you were looking to investigate?

First off, Roundup is smack in the middle of sagebrush rangeland, so it was a good site for that reason alone. But more importantly, there were different types of land uses near Roundup that allowed us to look into how grazing affects pollinators: SGI-enrolled pastures which employed rest-rotation grazing, grazed pastures which were not enrolled in SGI, and the Lake Mason National Wildlife Refuge where cattle grazing had been absent for over a decade. These distinct land uses allowed us to focus in on the possible effects of grazing on pollinators in a real-world setting.

In terms of pollinator conservation, my big questions were: How do different land uses affect where bees forage for resources and are there more Genera (different types) of bees in certain types of land uses?

I mapped out plots on each land use type and then used “pan traps” to measure how many different types of bees were using each land type and how many individual bees were using each site. Once a week, I collected the samples and brought them back to Montana State University where I cleaned, identified, and pinned each individual specimen.

Roundup, Montana where Blanchette conducted her study. Photo: Gabrielle Blanchette.

What did you find? What surprised you the most?

My study had two goals. First, I wanted to systematically collect and catalog bees down to Genera in an area of Montana where that type of collection hadn’t been done yet. Second, I wanted to examine if and how grazing affects pollinators.

Regarding my first goal, I found many different native bee Genera that were consistent with findings from studies across the U.S. that also cataloged native pollinators. Additionally, I found many individuals from the Genus Macrotera, a bee not commonly found as far north as eastern Montana. This could be evidence of a possible range expansion due to a changing climate that makes eastern Montana a warmer and now useable habitat.

For my second goal, I found that pollinators were more abundant in pastures with livestock grazing as compared to pastures with no livestock grazing.

Some people may be surprised by this finding (that pollinators were more abundant in areas with livestock grazing than in areas without), but I was most surprised by the sheer number of sweat bees I collected: 7,285 across all three study years and pasture types. No one had yet catalogued native bees in this area, and I was surprised simply because I did not know what I was going to find. I ended up discovering how abundant these bees are in Roundup.

Your study points out that pollinator abundance was more correlated to bare ground and surface litter than to the presence of native flowering plants. That seems counter-intuitive. How do you explain that?

Ultimately each species of native bee has their own preference of habitat characteristics. However, about 70% of North American native bees nest within the soil. Having an open, sunny area with access to excavate or occupy an abandoned nest is essential for these types of bees to be able to reproduce. So, patches of bare ground provide the access to soils that bees need for their nesting cavities. The remaining 30% nest within old stumps, tree cavities and dead plant stalks, generally considered surface litter. Pollinators, in general, are highly mobile organisms, so as long as they can find floral resources rich in pollen and nectar nearby their nesting sites, they’re ok.

A native pollinator ready for cataloging. Photo: Gabrielle Blanchette.

Are there other possible explanations like weather, moisture, elevation or other variables that could impact the abundance of pollinators?

Yes. The activity of bees is impacted by many variables. For example, many pollinators cannot forage or fly in severe wind, rain, or hail. Elevation, water availability, time of day, and areas that contain pristine nesting or foraging resources all impact where pollinators tend to accumulate. However, the methods of my study were designed to eliminate bias associated with those factors so we could more directly attribute bee activity with the associated grazing treatments.

How does soil health fit into this picture?

Because so many of our native pollinators are ground nesters, soil health is really important for two main reasons. First, ground-nesting bees have been found to select sandy, well-drained soils for nesting sites due (we think) to ease of nest excavation. Second, healthy soils are essential for healthy populations of the floral resources that are essential to pollinator survival. There’s a bit of a feedback loop: healthy soils provide good nesting habitat for pollinators. Abundant pollinators help native plants reproduce more effectively. More abundant and healthy native plants improve soil health, which improves pollinator abundance, which improves native plant abundance, and so on.

How do your findings fit with other research on the effects of grazing in sagebrush-steppe, and particularly, grazing and sage grouse?

Well, I can say that my study showed that lands with grazing produced better habitat for native pollinators. My thesis advisor, Dr. Hayes Goosey, did a study a couple of years ago that showed that there were more arthropods that sage grouse like to eat in grazed pastures compared to pastures that hadn’t been grazed. These two studies suggest that grazed rangelands produce better habitat for sage grouse. Obviously, intensive grazing can be detrimental to rangeland health, but these studies show that some amount of grazing produces quality habitat for sagebrush obligates like sage grouse.

What are the implications of your findings on conservation in the sagebrush ecosystems of the American West? In other words, what does this mean for sagebrush conservation efforts?

Understanding how pollinators fit into the sagebrush picture can be beneficial to land management. I hope these results are used to help conserve native sagebrush-steppe habitats from conversion into crop land. The results from this study indicate that native bee Genera are a crucial part of native ecosystems and that as private and governmental agencies move forward with conservation, pollinators need to be a part of the discussion and management efforts. Bees are easily captured and can serve as relative indicators of ecosystem health, and I would like to see steps taken to highlight and use bees to monitor ecosystem health.

Meet the expert

Study author, Gabrielle Blanchette. Photo courtesy of Gabrielle Blanchette.

This study was your thesis. Congratulations on graduating. What’s next for you?

Thank you! The world is full of possibilities and I am continuing my search for a conservation, ecology, and/or entomology opportunity. In the meantime, I am working on publications for my thesis and learning to ski!

Have you had a long-standing interest in bees and insects or is your focus on these small, but important, creatures a result of your studies?

Well, as an undergrad majoring in biology I quickly found myself in a lab feeding blood worms to leeches and sexing jewel wasps. So, I guess you could say invertebrates have been a long-standing interest that eventually shifted to insects and further narrowing my focus to native bees.

What’s your favorite type of bee?

I find leaf cutter bees to be very fascinating. Females cut small pieces of leaves to line their nests and some species use flower petals. Plus, they are quite cute up-close under a microscope!

What do you like to do when you’re not counting and identifying bugs?

I enjoy the outdoors and when the weather permits, killing it at badminton. I also enjoy traveling, going to the gym, camping, and learning new things (like pottery and tennis).

>>Learn more about how the USDA-NRCS is helping pollinators<<

>>