Taking the Bias Out of Sage Grouse Nesting Studies

This new Science to Solutions shows that grass height may not be as crucial to nesting success as previously thought, since hatched nests are measured later than failed nests.

VIDEOS | Meet The Thomas Family, Sustainable Ranchers in Idaho

November 20, 2017A Tale of Two Fires: Prescribed Fire Thwarts Wildfire on the New Mexico Prairie

November 29, 2017

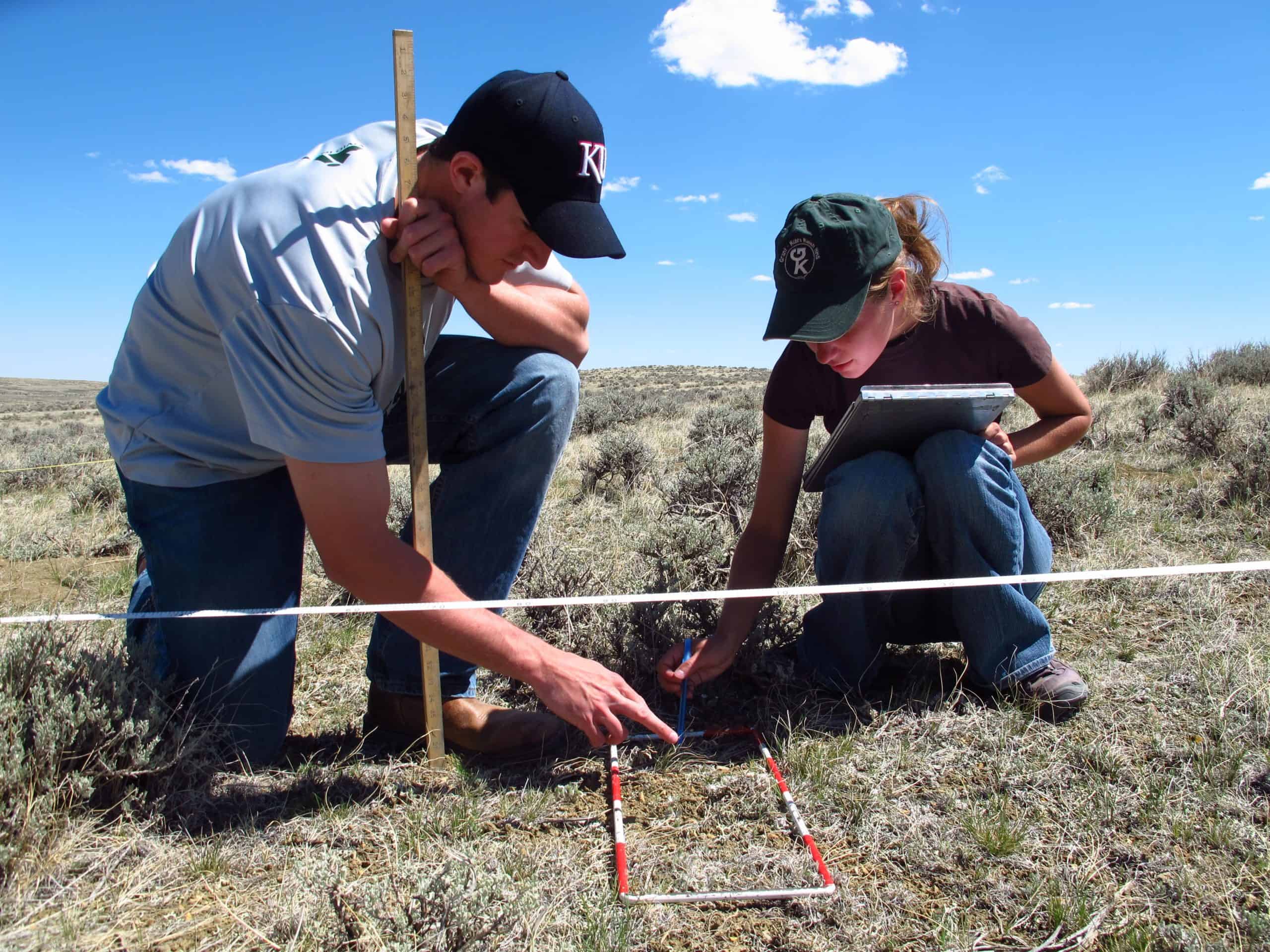

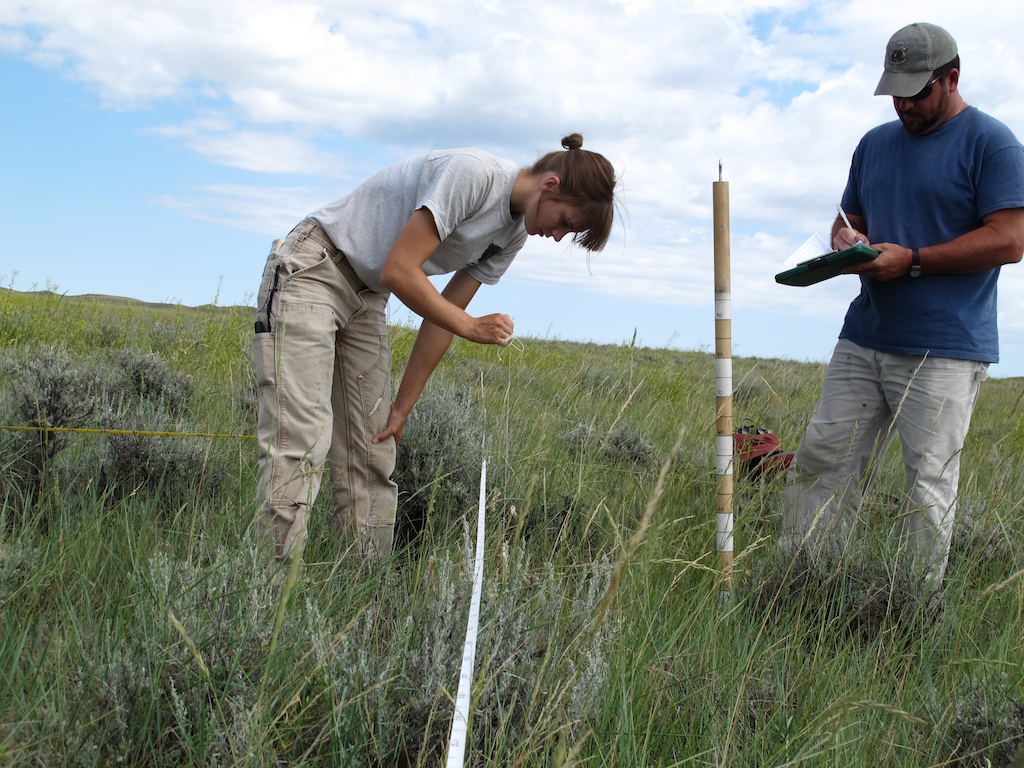

New findings show that it’s more accurate to measure grass height for all nests – failed or hatched – at the predicted hatch date. Photo: Joe Smith

Grass height may not be as crucial to nesting success as previously thought, since hatched nests are measured later than failed nests, giving grasses more time to grow. Photo: Joe Smith

Download a PDF of this Science to Solutions

New findings show that it’s more accurate to measure grass height for all nests, failed or hatched, at the predicted hatch date

When managing habitat for sage grouse, adequate grass height for hiding cover has been emphasized as an important component for these ground nesting birds. However, new findings that replicate previous work further validate that methods now known to be biased are often responsible for identifying grass height as an important driver of nest success.

Together, these studies suggest that the common practice of measuring grass height around nests directly following nest failure or hatch can lead to a false positive signal that indicates grass height is correlated with nest success even when they are unrelated. This is because hatched nests are measured later in the season than failed nests, which gives grasses more time to grow.

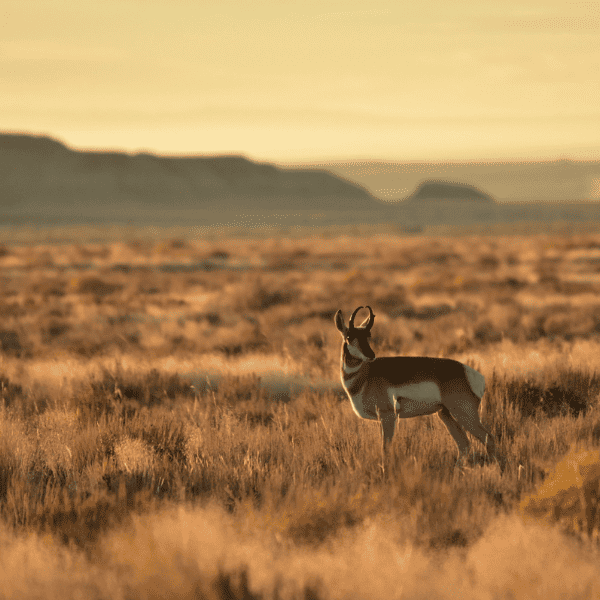

A radio-collared sage grouse hen hunkers down. Native grasses and forbs are key components of healthy sagebrush rangelands and high-quality sage grouse habitat. Photo: Tatiana Gettelman

Led by Joe Smith from the University of Montana, the authors re-evaluated more than 800 nests from several studies that originally showed a positive correlation between nest success and grass height. After correcting the data to account for grass growth, researchers found no relationship between grass height and nest fate. Following correction, median grass heights at hatched and failed nests were within 0.05 inches of one another (the thickness of a penny) across all re-analyzed datasets.

These findings suggest that the height of grass may not be as crucial to sage grouse nesting

success as previously thought.

Researchers recommend waiting to measure grass height until after the predicted hatch date for all nests (failed or hatched) to ensure unbiased sampling. Photo: Joe Smith

The key takeaway for researchers is to reduce the likelihood of biased results by waiting to measure grass height until after the predicted hatch date for nests. Measuring vegetation as quickly as possible after the incubating female has left the nest should be avoided (currently a common practice among nesting studies of sage grouse and other ground nesting birds).

In addition, Smith’s findings should encourage a critical re-evaluation of habitat management guidelines that are based on research now known to have inadvertently used biased methods. Native grasses and forbs are key components of healthy sagebrush rangelands and high-quality sage grouse habitat, but the importance of tall grass for concealing nests from predators has likely been overstated.

While getting the science right on grass height may challenge long-held perspectives about the role of grazing and grass height in sage grouse habitat management, it also may provide added flexibility for managers to work together with ranchers to achieve overall ecosystem goals in the face of increasingly complex and persistent threats.

Smith and colleagues caution not to interpret their findings to imply that grazing does not matter. Rather, they suggest fundamental, time-tested range management principles be employed as a tool to ensure sage grouse and other wildlife have the resources they need.

Time-tested range management principles promote diverse and resilient plant communities including native grasses, ensuring sage grouse and other wildlife have the resources they need. Photo: Brianna Randall

These new findings provide an opportunity for scientists and managers to set down our rulers, step back, and look at the bigger picture. By promoting robust and diverse native perennial plant communities, managers can ensure that rangelands remain resistant and resilient so that drought, exotic annual grass invasions, and catastrophic wildfires are less likely to impact birds.

Done sustainably, ranching is a highly compatible land use for supporting sagebrush-dependent wildlife, and a preferred alternative to cultivation and housing developments that reduce and fragment the vast landscapes sage grouse need to thrive.

Download the Science to Solutions: Taking The Bias Out Of Sage Grouse Nesting Studies

Read the article in Ecology and Evolution: Phenology largely explains taller grass at successful nests in greater sage-grouse