Publication Alert

Where trees meet sage: Striking a balance between sage grouse and pinyon jay needs

Research from two papers helps managers balance conservation to benefit imperiled sagebrush and woodland birds species.

Podcast: How Invasive Grasses Are Harming Hunting

April 19, 2023

How can we balance sage grouse and pinyon jay conservation in sagebrush country?

May 17, 2023

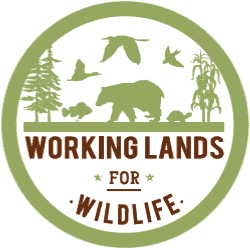

New research and maps shows most conifer removal in sagebrush country is already avoiding pinyon jay strongholds but additional targeting can further optimize management to benefit both species.

Effective conservation avoids creating “winners and losers” by balancing the diverse habitat needs of different species that live in a particular landscape. In sagebrush country, the intersection of historic shrublands with woodlands and forests makes it challenging to meet differing habitat requirements of sagebrush- and woodland-obligate bird species. This issue is especially urgent because of ongoing woodland expansion and infilling that is affecting imperiled habitats and species.

Expanding pinyon-juniper woodlands and conifer forests have pushed sage grouse and other sagebrush-dependent songbirds, like the sage thrasher and Brewer’s sparrow, out of formerly occupied habitat. However, other wildlife rely on pinyon-juniper woodlands. Many populations of pinyon-juniper dependent birds have remained steady or grown during the last century of tree expansion. One main, and critically important, exception to this is the pinyon jay.

Pinyon jays have experienced significant declines in recent decades, generating strong interest in their conservation. Yet, there are persistent and significant gaps in knowledge regarding how pinyon jays use pinyon-juniper woodlands and why their populations are declining while woodlands are increasing across western rangelands. Also, pinyon jay use of conifer-encroached sagebrush shrublands has called into question the potential impacts of sagebrush-focused conifer removal may have on pinyon jay populations. Two recently published papers begin to fill some of these knowledge gaps.

The first paper is called “Regional Context for Balancing Sagebrush- and Woodland-Dependent Songbird Needs with Targeted Pinyon-Juniper Management in the Sagebrush Biome.” With data from the annual Breeding Bird Survey, the team led by Jason Tack, a WLFW-affiliated researcher with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, mapped the distribution and abundance of nine sagebrush- and woodland-dependent songbirds across the sagebrush biome. Next, the authors overlaid Sage Grouse Initiative-sponsored conifer removal treatments onto the bird maps to compare where past cuts occurred relative to where different bird species live.

Findings show that SGI-sponsored conifer removal conducted over the last decade has largely avoided where most pinyon jays live. The study provides the first quantitative assessment demonstrating that targeted sage grouse habitat restoration under one of the largest conservation initiatives in the biome does not appear to be at odds with protecting pinyon jay populations in most regions despite suggestions to the contrary.

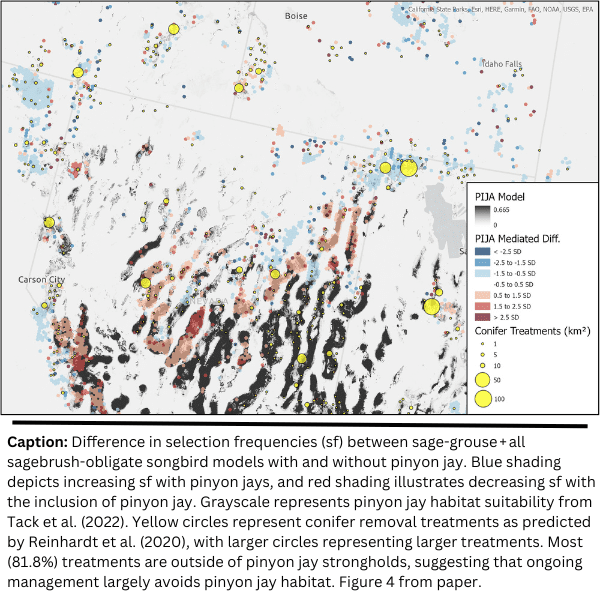

The second paper, authored by Jason Reinhardt, a research forester with the U.S. Forest Service, with support from WLFW scientists, is called “Optimizing Targeting of Pinyon-Juniper Management for Sagebrush Birds of Conservation Concern While Avoiding Imperiled Pinyon Jay.” The paper used an optimization modelling approach to show how conservation planners could balance sagebrush- and woodland-obligate species needs relative to pinyon-juniper management across the sage grouse range.

This work illustrates how multi-species habitat needs can be combined in a systematic conservation planning approach to steer the right actions in the right places to benefit sagebrush-obligate birds while avoiding pinyon jay strongholds. The study also compared the conifer optimizations with ongoing conifer removal efforts and found that only a small proportion (13-18%) of cuts had occurred on areas predicted as being important for pinyon jay, suggesting that targeted management in sagebrush country is already avoiding most critical pinyon jay habitat areas.

This research is helping inform WLFW’s proactive, core-focused Framework for Conservation Action in the Sagebrush Biome and next-generation targeting tools being developed in support the interagency Sagebrush Conservation Design. Striking the delicate balance of meeting multiple species habitat needs where the trees meet the sage helps ensure proactive management of core sagebrush habitats to address primary threats like encroaching conifer trees or annual invasive grasses can continue while avoiding unintended consequences for other species and ecosystems of conservation concern.

Regional Context for Balancing Sagebrush- and Woodland-Dependent Songbird Needs with Targeted Pinyon-Juniper Management in the Sagebrush Biome

Abstract: In the western United States, pinyon-juniper woodlands have expanded by as much as sixfold among sagebrush landscapes since the late 19th century, with demonstrated negative impacts to the behavior, demography, and population dynamics of species that rely on intact sagebrush rangelands. Notably, greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) are unable to tolerate even low conifer cover, which can result in population declines and local extirpation, whereas removing expanding conifer cover has been demonstrated to increase sage grouse population growth rates and sagebrush obligate songbird abundance. Yet conifer management among sagebrush landscapes has been met with concerns about unintended impacts to species that rely on conifer woodlands, notably the pinyon jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus), whose population declines are distinctive among birds breeding in pinyon-juniper woodlands. Spatial models of bird abundance can help management prioritize future actions in light of multiple species requirements, while also providing a framework to retroactively test the impact of past treatments. We used Breeding Bird Survey data to model indices to abundance in relation to multiscale habitat features including landcover, fire, topography, and climate variables for nine songbird species reliant on sagebrush and pinyon-juniper woodlands for breeding. Predictive maps allowed us to also examine the overlap of conifer management conducted by the Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI), which targets management of early successional conifers among priority sage-grouse habitats, with predicted indices to abundance of songbirds. Our findings demonstrate that targeted sage grouse habitat restoration under SGI was not at odds with protection of pinyon jay populations. Rather, conifer management has largely occurred among northern sagebrush landscapes where models suggest that past cuts likely benefit Brewer’s sparrow and sage thrasher while avoiding pinyon jay habitats.

Citation: Jason D. Tack, Joseph T. Smith, Kevin E. Doherty, Patrick J. Donnelly, Jeremy D. Maestas, Brady W. Allred, Jason Reinhardt, Scott L. Morford, David E. Naugle, “Regional Context for Balancing Sagebrush- and Woodland-Dependent Songbird Needs with Targeted Pinyon-Juniper Management”, Rangeland Ecology & Management, Volume 88, 2023, Pages 182-191, ISSN 1550-7424.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the many volunteers and staff that support the collection and distribution of data for the Breeding Bird Survey. The Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies provided support through the Sagebrush Science Initiative. C. Wiggins identified BBS stop locations, and S. Somershoe, S. Fields, M. Estey, R. Pritchert, and K. Barnes all provided helpful input. N. Niemuth provided invaluable guidance on the framing of the analyses and writing of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. government determination or policy.

Permanent URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2023.03.006

Optimizing Targeting of Pinyon-Juniper Management for Sagebrush Birds of Conservation Concern While Avoiding Imperiled Pinyon Jay

Abstract: Contemporary restoration and management of sagebrush-dominated (Artemisia spp.) ecosystems across the intermountain west of the United States increasingly involves the removal of expanding conifer, particularly juniper (Juniperus spp.) and pinyon pine (Pinus edulis, P. monophylla). The impetus behind much of this management has been the demonstrated population benefits of sagebrush restoration via conifer removal to greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), a species of conservation concern. One of the challenges with scaling up from a focal-species approach to a community-level perspective, however, is balancing the habitat requirements of different species, some of which may overlap with sage-grouse and others which may have competing habitat needs. Here, we use a systematic conservation planning approach to compute spatial optimizations that prioritize areas for conifer removal across the sage-grouse range while incorporating woodland and sagebrush songbirds into decision making. Three of the songbirds considered here, Brewer’s sparrow (Spizella breweri), green-tailed towhee (Pipilo chlorurus), and sage thrasher (Poocetes gramineus), are sagebrush-obligates, while another is a woodland-obligate, the pinyon jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus). We find that the inclusion of sagebrush-obligates expands the model-selected area of consideration for conifer management, likely because habitat overlap between sagebrush-obligates is imperfect. The inclusion of pinyon jay, a woodland-obligate, resulted in substantial shifts in the distribution of model-selected priority areas for conifer removal, particularly away from pinyon jay strongholds in Nevada and east-central California. Finally, we compared the conifer optimizations created here with estimates of ongoing conifer removal efforts across the intermountain west and find that a small proportion (13−18%) of management efforts had occurred on areas predicted as being important for pinyon jay, suggesting that much of the ongoing work is already successfully avoiding critical pinyon jay habitat areas.

Citation: Jason R. Reinhardt, Jason D. Tack, Jeremy D. Maestas, David E. Naugle, Michael J. Falkowski, Kevin E. Doherty, “Optimizing Targeting of Pinyon-Juniper Management for Sagebrush Birds of Conservation Concern While Avoiding Imperiled Pinyon Jay”, Rangeland Ecology & Management, Volume 88, 2023, Pages 62-69, ISSN 1550-7424.

Acknowledgements: This study was funded by the Sagebrush Science Initiative, a collaboration between the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resource Conservation Service’s Sage Grouse Initiative. Funding sources were not involved in the data collection, study design, analyses, or interpretation. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. government determination or policy.

Permanent URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2023.02.001