Ask an Expert

How can we balance sage grouse and pinyon jay conservation in sagebrush country?

Two recent papers highlight that the majority of conifer removal in sagebrush country has avoided key pinyon jay habitat and further detail how we can balance managing pinyon jay habitat with sage grouse habitat in western rangelands.

Where trees meet sage: Striking a balance between sage grouse and pinyon jay needs

May 12, 2023

Podcast: Predicting Fire in the Great Basin

June 16, 2023

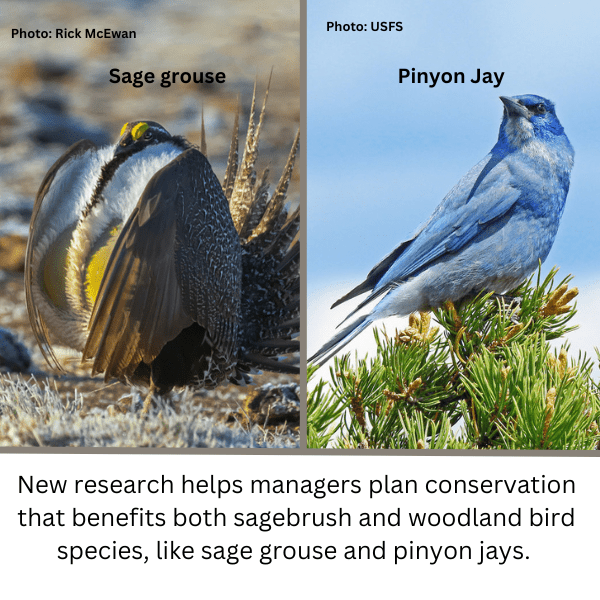

New research supports conservation planning to benefit both sagebrush and woodland birds of conservation concern.

Pinyon-juniper woodlands have always been part of the fabric of western landscapes. Historically, these woodlands were restricted primarily to areas where grassy fuels were limited. Periodic fire, and occasionally severe drought, killed trees and maintained a balance of grasslands, shrublands, and woodlands. However, altered fire regimes have allowed more trees to establish and grow, spread by seeds that are dispersed by birds and small mammals.

Tree encroachment into formerly treeless shrublands has proven particularly impactful to unique wildlife species like sage grouse, who completely avoid otherwise suitable habitat when only a few trees break up large expanses of sagebrush. Many other sagebrush-dependent wildlife as well, notably songbirds like sagebrush sparrow and sage thrasher, are in this same predicament. They have all experienced steep populations declines as their expansive and open rangelands have been converted to savannas or even woodland forests.

For more than a decade, the Sage Grouse Initiative has worked with landowners in sagebrush country to turn this tide, restoring sagebrush shrublands by strategically removing encroaching conifers like pinyon and juniper. These efforts have proven extremely effective for sagebrush-dependent wildlife like sage grouse.

However, other wildlife rely on pinyon-juniper woodlands for their survival. Most species of woodland-dependent birds have benefited from a century of tree expansion, and their populations have remained steady or grown with increasing woodlands. For example, abundance measurements for gray flycatcher, a species that breeds in pinyon-juniper woodlands in the Intermountain West and the Great Basin, have risen roughly 50% over the last 50 years.

One main, and critically important, exception to this is the pinyon jay, a songbird that depends on pinyon-juniper woodlands. Pinyon jays have experienced significant population declines in recent decades, which has generated strong interest in conserving pinyon jay populations. However, there are significant gaps in knowledge regarding pinyon jays, how they use pinyon-juniper woodlands, why their populations are declining even as woodlands continue to expand, and how conifer removal may impact them.

This limited understanding has complicated efforts to restore sagebrush rangelands, where balancing conservation of sagebrush-dependent wildlife, like sage grouse, with woodland-dependent wildlife, like pinyon jays, has resulted in perceptions that some species are winning and others are losing as conifer management strategies are expanded.

Two recently published papers help fill in these knowledge gaps and highlight that there are vast amounts of sagebrush country where, with science-backed and spatially informed conservation planning, we can restore sagebrush country while also balancing the needs of woodland obligates.

The first – “Regional Context for Balancing Sagebrush- and Woodland-Dependent Songbird Needs with Targeted Pinyon-Juniper Management in the Sagebrush Biome” – examined if SGI-sponsored conifer management has impacted pinyon jays.

The second – “Optimizing Targeting of Pinyon-Juniper Management for Sagebrush Birds of Conservation Concern While Avoiding Imperiled Pinyon Jay” – details a new optimization model that helps balance pinyon-juniper management so that it benefits sagebrush and woodland-obligate species.

We sat down with the lead authors of both papers – Jason Tack, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Jason Reinhardt, a research forester with the U.S. Forest Service – to better understand their research and if and how conifer management in sagebrush country can benefit both sage grouse and pinyon jays.

Will you start by sharing what’s happening with pinyon-juniper woodlands in sagebrush country?

Reinhardt: Let’s go back in time to the earliest reports we have of what these landscapes looked like. The West’s first explorers described vast expanses of sagebrush-dominated rangeland. While they didn’t use these exact words, they also observed that pinyon-juniper woodlands existed in certain spatial configurations like rocky draws and rimrock, northern aspects, and at higher elevations. This was due to the primary role fire played in constraining woodlands.

As colonization came, so did fuels manipulation and fire suppression. Early settlers brought livestock which removed grassy fuels that fed fire. Later in the 1900s, active fire suppression also reduced the role of fire, allowing trees to move beyond historic locations.

Altered fire regimes impact sagebrush and woodland ecosystems in two ways. The first is when trees move into places they weren’t historically. This is called encroachment. The second is when existing woodlands become denser. This is called infill.

Expansion causes one set of challenges. Sagebrush-dependent wildlife moves out. Native grasses, shrubs, and other species are displaced by trees. Water supplies and soil moisture are reduced.

Infill causes other issues. As trees get older and stands get denser, the health of the stand degrades. You get insect infestations, fungus, and other threats that impact the overall health of the stand and the specific trees within it. Stressed trees are also more susceptible to drought-induced die-offs and to fire.

Even though these changes happen relatively slowly, we can see the shifts by comparing historic photos with ones from today. In some places, like the Great Basin, we’ve seen a 650% expansion of woodlands, but it’s happening all across sagebrush country even if it’s less extreme than in the Great Basin.

We’re at a point in sagebrush conservation where all these management challenges are coming to a head. Encroaching trees are displacing sagebrush-dependent wildlife. Infill is making old-growth woodland stands less healthy. Figuring out how to balance the conservation of sagebrush- and woodland-dependent species is the next challenge for scientists and managers working in sagebrush country.

We’re talking about a vast area here, are there differences in how pinyon-juniper trees are spreading in different locations across the West?

Reinhardt: Yes. In the more northern parts of sagebrush country, Oregon is a good example, we’re seeing lots of encroachment. Farther south, in the Great Basin, we’re seeing lots of infill. And in places like northern Arizona, New Mexico, and southern Utah, we’re starting to see drought-induced mortality of pinyon-juniper forests, which is something we haven’t really seen before.

Tack: As Reinhardt explained, the historic balance between woodlands and sagebrush range has been upset. Sage grouse conservation has played an important role in how we’ve managed expanding conifers in sagebrush country but there are other species that we need to include in our sagebrush conservation strategies.

What does all this mean for sagebrush rangelands and the species that depend on sagebrush habitat?

Tack: Both studies support proof-of-concept for the body of work that’s out there showing conifer management has benefits for sagebrush habitats. They also show that we don’t have to rob Peter to pay Paul in terms of sensitive species. We can find ways to manage conifers to benefit both sage grouse and pinyon jays.

In other words, we need management strategies that are better suited to the unique attributes of both sagebrush-steppe habitat and pinyon-juniper woodland habitat. We know that pinyon-juniper trees have always existed in the West’s sagebrush rangelands. We know that cutting encroaching conifers benefits sage grouse and other sagebrush-dependent species. We also know that trends of most woodland-dependent songbirds are either stable or increasing.

All of this means that we can’t treat these two systems independently any longer. Studying pinyon jays is a great way to find that balance. They need mixed-age, healthy pinyon-juniper woodlands that produce lots of pinyon seeds, and they also need sagebrush to cache those seeds. We need holistic strategies that improve sagebrush range and the health and resiliency of pinyon-juniper woodlands.

Will you walk us through your research and explain what you did?

Tack: The first thing we did was to map where certain sagebrush- and woodland-dependent songbirds live. This may seem basic, but it hadn’t really been done yet. In short, we used data from the annual Breeding Bird Survey to map the abundance of different species of birds to understand how they are distributed across the sagebrush biome. Then we overlaid SGI-led conifer cuts onto the map to compare where those cuts occurred with where different bird species live. We used SGI cuts and not other conifer removal cuts because we knew SGI’s were done solely for conservation, not for fuels management or other reasons.

We found that the vast majority of SGI cuts avoided areas where pinyon jays live and therefore had very little impact on pinyon jays.

Reinhardt: We set out to build on previous work that looked at where to prioritize conifer management for sage grouse. Focusing on sage grouse is a fine strategy for conserving sagebrush-steppe habitat. Sage grouse are a good “umbrella species.” In other words, if we conserve sagebrush for sage grouse, we also conserve it for a host of other species that use sagebrush habitats.

But we wanted to help land managers develop conservation plans that optimize conifer management for multiple species, including woodland obligates. Our goal was to develop an “optimization model” that allows us to find the places in sagebrush country where we can maximize conservation benefits while minimizing costs, whatever those benefits or costs might be. For example, if we want to maximize sage grouse habitat restoration while minimizing habitat reductions for woodland obligates, we can use the model we developed to target a specific location or a specific treatment type that achieves our goals.

Our paper outlines how we built the model and makes it available to anyone working in sagebrush country.

How have SGI’s efforts successfully removed conifers without having unintended consequences for woodland obligates?

Tack: It’s important to acknowledge that there are a lot of reasons people cut conifers from sagebrush. Obviously, species conservation is a big one. But there are others like fuel reduction or livestock production. Our research focused on the wildlife conservation aspect of conifer management and that’s why we used SGI cuts – we knew they were done to benefit sage grouse.

Aside from the simple fact that SGI’s efforts were focused on wildlife conservation and not fuels reduction or livestock, there are two main reasons why this work generally avoided pinyon jays.

First, SGI’s efforts primarily target the early stages of encroachment, where trees are just starting to move into sagebrush. Because the trees haven’t yet become woodlands, they don’t host woodland obligates, so cutting them has little impact. SGI avoids areas where trees have existed historically because sage grouse don’t live in those places and never have.

Second, and more specific to pinyon jays, SGI has generally worked north of pinyon jay population strongholds. So even when the projects do cut what might be considered a true “woodland,” they aren’t in prime pinyon jay territory.

This isn’t a happy accident. SGI spent a lot of time and energy into prioritizing sage grouse core areas and focusing its conservation on defending and growing those intact cores. Because sage grouse rely on sagebrush, these areas have never been great for woodland obligates anyway.

Reinhardt: We looked at places where conifers were removed across the sagebrush biome for all reasons, not just wildlife, but we didn’t separate out why those reductions occurred. We found that roughly 85% of all conifer removal in the last decade was outside of pinyon jay habitat. So regardless of if these reductions were achieved through a wildfire, a fuels-reduction project, or for wildlife conservation, they still largely avoided pinyon jays.

SGI works only on private lands. Is there a public land connection here?

Reinhardt: I can’t speak for the Forest Service as an agency, but I can say that there is a growing interest in the field of forestry in looking at pinyon-juniper management across the southwestern U.S. Part of that is driven by fire and fuels management, but conservation of pinyon jays is playing a bigger role now, too. There hasn’t really been much management of these types of woodlands to date, aside from fuels reduction or sage grouse conservation. But it’s exciting to see the folks eager to study and manage pinyon-juniper woodlands to benefit the health and resilience of these important ecosystems, and pinyon jay in particular.

Are you suggesting that sagebrush country needs a holistic approach to conifer management that incorporates multiple species rather than a piecemeal approach that targets species in one location?

Reinhardt: My goal, and a big part of why I led this study, is to improve the management of pinyon-juniper woodlands by incorporating high-quality science. There are a lot of gaps in pinyon jay and pinyon-juniper ecology, so we have a lot of work to do as a scientific and management community. We don’t want to fall into a trap of “winners and losers.” The same changes in historic fire and grazing regimes have driven both encroachment and infill, so we’re working to learn how we can manage these lands to better reflect the historic ecology of pinyon-juniper woodlands.

We’ve seen pinyon-juniper woodlands increase in size and extent even as we’ve seen declines in pinyon jay populations, so I don’t think it’s a quantity issue. It’s a quality issue. I hope we can get to a watershed management approach that manages historic pinyon-juniper woodlands for pinyon jays and other woodland obligates, while also managing pinyon-juniper encroachment lower in the watershed where sagebrush obligates live.

Are there other wildlife management efforts that could benefit from the type of spatial modeling that this research developed?

Tack: No one in conservation wants to pit one species against another; in this case, sage grouse against pinyon jays so that one species wins out while the other loses. The optimization modeling that Reinhardt and his team developed is a way to plan conservation projects so that we avoid winners and losers. While it was developed for pinyon jay and sage grouse, it’s really about balancing conservation goals whatever they may be. With the right inputs, it can be applied to any conservation challenge where management actions need to benefit multiple species at once, even if they have competing habitat needs.

Reinhardt: The optimization modeling is fairly new and provides a general approach to landscape conservation design where different species with different habitat needs are competing. I’m not as familiar with other use cases, but I know it’s been used for invasive species management and for prioritizing habitat while minimizing road-related mortality for grizzly bears in Canada.

What’s next for your research?

Reinhardt: My next step is to work with other researchers to fill in those knowledge gaps around pinyon-juniper woodland stand dynamics. We need to better understand how pinyon pines recruit and change over time. We also need to compare reference stands to stands where management has occurred, so we’re setting up some experiments to do all of this. We’re hoping for these to be long-term studies since trees, and especially pinyon-juniper, do take some time to grow.

I’m also applying what we’ve learned about conifer management planning through the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Sagebrush Conservation Strategy. That effort will result in a lot more on-the-ground work, and I’m leading the spatial modeling component of conifer management so we can better balance sage grouse and pinyon jay conservation across the biome.

Tack: I’m going to be expanding my work with Breeding Bird Survey data to come up with a core area strategy for pinyon jay. As Reinhardt noted, there’s just not a lot of science-backed information out there about pinyon jays, including where their population strongholds are and where we should be prioritizing management. Fortunately, there are now several large-scale research projects underway, including radio-telemetry studies of pinyon jays in areas where there is active management and a more robust territory monitoring protocol thanks to the pinyon jay working group. These efforts will put us in a far better place for understanding how pinyon jays use pinyon-juniper woodlands and for management to do right by both sagebrush and woodland obligates. Ultimately, I hope a broad coalition of managers and researchers beyond just wildlife biologists can co-produce watershed management plans that cover the entirety of the sagebrush biome, which includes both pinyon-juniper woodlands and sagebrush-steppe habitats.

At the end of the day, there is a huge, vast area where we can work to reverse conifer encroachment for the benefit of sagebrush obligates while avoiding pinyon jays. This is important for conservation in the sagebrush biome. It’s especially true if managers follow the Defend the Core strategy for woodland management where they focus on protecting cores where trees are just starting to move in. Pinyon jays, and other woodland obligates, don’t live in those areas, so it’s a win-win for conservation. As we start to build out pinyon jay core areas, I think we’ll find even more areas where we can work to benefit both species.

MORE RESOURCES