“Defend the Core” — Fighting back against woody invaders on the Great Plains

NRCS’ Working Lands for Wildlife is investing in big-picture, proactive ways to keep from losing healthy grasslands to woody infestations.

“Defend the Core” — Fighting back against rangeland invaders in sagebrush country

February 24, 2022

The Last Continuous Grasslands on Earth

March 3, 2022

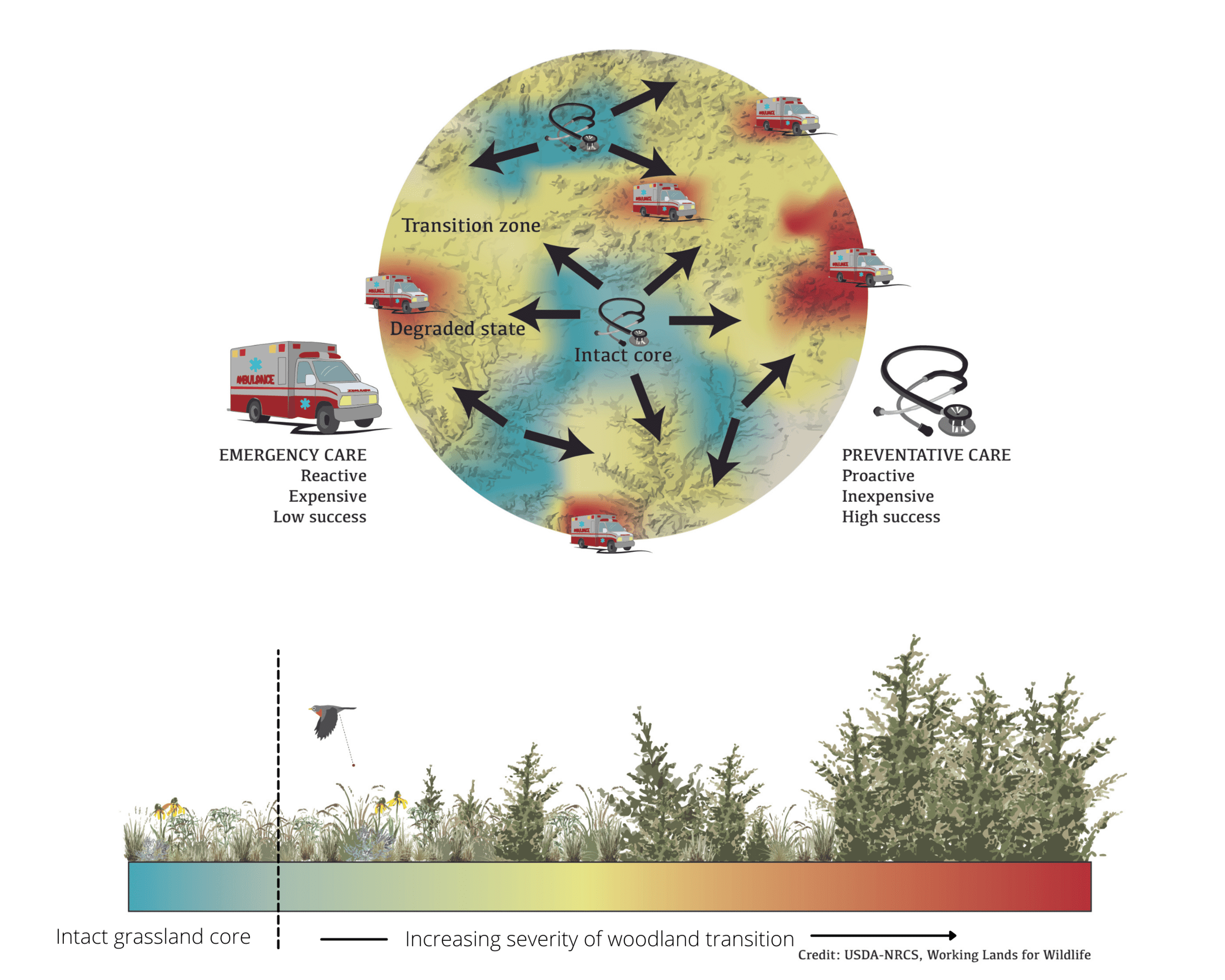

Defending intact grassland cores from woody species is more effective, cost-efficient and produces better results for grassland conservation.

By Brianna Randall

Envision driving across the prairie with the windows down. Little bluestem and switchgrasses wave in the wind. Cone flowers, milkweed, and black-eyed susans peek above the sea of green, surrounded by butterflies, birds, and bumblebees. This is what we call the intact core—vast swaths of healthy, thriving native grassland.

But as you drive farther, you start to notice invading woody species like eastern redcedar, mesquite, or Siberian elm. Prairie chickens, pronghorn, and other grassland-dependent wildlife are less abundant. Drive even further from the core, and the once-productive prairie has turned into a shrub-like forest. Once grasslands are infested with trees, they are much less productive for ranchers and wildlife—and extremely difficult to restore.

Across the Great Plains, invading trees are taking grasslands out of agricultural production and away from wildlife. Denser stands of eastern redcedar trees also increase the transmission of insect-borne diseases like Lyme’s and West Nile virus and fuel more intense wildfires that are expensive and dangerous to control.

Luckily, people who depend on and care about America’s valuable grasslands are banding together to fight back against unwanted invaders like redcedar. Through Working Lands for Wildlife (WLFW), the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) is investing in a new, proactive strategy to reduce woody encroachment: First, defend the core. Second, grow the core. Third, mitigate impacts in heavily infested areas.

Prevent seeds from taking root

If it sounds like battle tactics, that’s because Great Plains landowners are indeed engaged in a war on woody species. A shift in strategy is overdue since the status quo—reactive, piecemeal treatments once trees are already established—hasn’t worked.

Instead of chasing the invasion by triaging already-invaded areas, WLFW is flipping the script to prioritize preventative care for the best remaining intact grasslands in order to keep them productive and expand them.

“It’s much more economical and effective to prevent encroachment and stop seedlings from taking root in core areas rather than attempting to bring grasslands back from the brink after heavy infestations occur,” said Dirac Twidwell, a rangeland ecologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and a science advisor for WLFW.

Land managers have long known that it’s far more cost-effective and efficient to treat invasive species early, before they spread seeds and expand into new environments. However, on grasslands, this knowledge was never applied to woody encroachment.

Twidwell calls it “Invasion 101”: the best way to stop prairies from turning into woodlands is to stop seeds from spreading, germinating, and becoming parent trees. A recent study from Twidwell’s lab showed 95 percent of encroaching seedlings grew within two football fields of a parental seed source, which means this is where we should focus prevention efforts.

But until recently, conservation practitioners lacked the big-picture technology to see where large tracts of intact grasslands remain, as well as where they are at risk from seed sources. They also lacked access to science-based management strategies for ways to most effectively address woody encroachment.

“We were managing the issue blindfolded,” explained Twidwell. “That’s why we’re losing the biome. Now we have the technology to pinpoint the problem, and the guidance to place the right practices in the right place to tackle it.”

Defend the core, grow the core

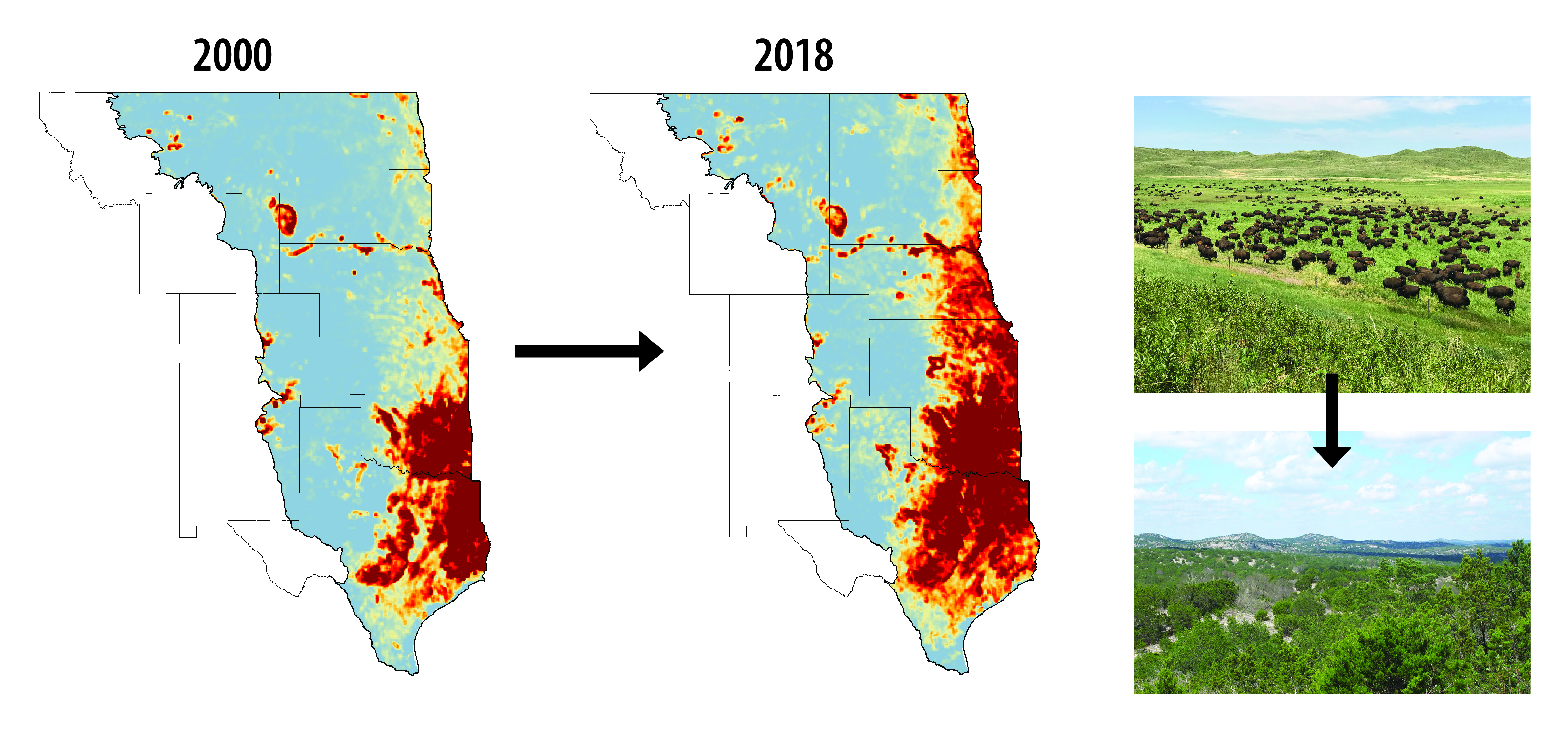

WLFW is partnering with local, state, and federal managers to produce statewide vegetation maps using the Rangeland Analysis Platform (RAP) and prioritize where to take action to manage woody expansion onto grasslands. Those maps are being paired with this new science-based guide on best management practices for reducing woody encroachment on rangelands, produced in partnership with several universities and extension faculty. Combined, these two resources are the basis of WLFW’s “Defend the Core” approach to conserving Great Plains grasslands.

“Our top priority is to secure core areas by keeping out seeds and young saplings,” Twidwell said. “Then we can grow and expand the core through strategic restoration.”

He points to Nebraska as an example: RAP data shows that seven million of 21 million intact grassland areas in the state are either at risk or already experiencing early signs of woody encroachment.

“Now that we know where at-risk grasslands are, we can apply the ‘Defend the Core’ approach, and coordinate management actions across property boundaries to prevent the continued expansion of woody plants,” Twidwell explained.

WLFW’s preventive approach for conserving grasslands includes these three tenets:

Defend the Core: Prevent seeds from becoming trees by using prescribed fire and eliminating seedlings with targeted herbicide use. Ensure “no new seed-bearing tree” and employ an “early detection-rapid response” strategy.

Grow the Core: Increase distance from the core to seed sources through prescribed fire, cutting trees, and/or using herbicides. Ensure that “no tree is left behind” and monitor to prevent future re-invasion.

Mitigate Impacts: Mitigate the most severe impacts within heavily infested areas. For example, protect houses and communities in heavily invaded areas from the more intense wildfires fueled by volatile woody species, like eastern redcedar.

Twidwell cautions that implementing management practices is not the goal, it’s simply the means to an end.

“The goal is to sustain grassland ecosystems for the long-term, which requires an integrated, collaborative approach, as well as consistent monitoring to ensure trees don’t contaminate core areas,” he said.

Hope in action

WLFW’s “Defend the Core” approach is already being deployed in Great Plains states beleaguered by invading trees. The Great Plains Grasslands Initiative (GPGI) is being implemented in multiple states to strategically reduce woody encroachment in prairie core areas by helping ranchers re-create “tree free, seed free” landscapes.

Kansas NRCS committed $3.9 million in 2021 — the first year that GPGI was launched — to help 63 landowners protect and expand native prairie across 100,000 acres. Nebraska and Oklahoma also launched GPGI efforts within the past year, applying similar locally-led strategies through GPGI to reduce woody invasion and conserve core grasslands. South Dakota is following suit and plans to release its version of GPGI in 2023.

WLFW is poised to help more states develop strategies to “Defend the Core”, guided by its framework for conservation action in the framework for conservation action in the grassland biome. In addition, WLFW is investing Farm Bill conservation dollars on thousands of acres of private agricultural land each year to encourage sustainable agricultural practices that help maintain grasslands and fight back against woody expansion.

“Our ‘Defend the Core’ approach is a proactive new business model for tackling one of the biggest threats to Great Plains grasslands,” said Twidwell. “By working collaboratively across large landscapes, producers can minimize risk, reduce the costs of managing woody encroachment, and better sustain prairies for generations to come.”

* This common strategy to protect—and grow—the best rangelands is also benefiting people and wildlife in sagebrush country, where the “Defend the Core” approach is keeping annual invasive grasses like cheatgrass at bay. Read more here.