Ask an Expert

Ask an Expert | The Green Glacier: What is Conifer Encroachment and Why is it Bad?

Learn about the “Green Glacier,” the slow-moving expansion of conifer trees across western rangelands, in this Ask an Expert with NRCS’s Jeremy Maestas.

Podcast: The New Great Plains Grasslands Initiative with NRCS

June 16, 2021Study Demonstrates Importance of Voluntary Conservation for Grassland Birds

July 1, 2021

Conifer encroachment into sagebrush-steppe is a threat to sage grouse and a significant management challenge. Woody species contribute to more severe rangeland fires, which add carbon to the atmosphere and reduce how much carbon native species store. Photo: Jeremy Roberts, Conservation Media

What is conifer encroachment? Why is it bad? What’s being done to halt it? This Ask an Expert has the answers.

As a general rule, humans love trees. It’s not surprising; there’s a lot about trees to like. Trees help clean our air, pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and help provide clean water. Studies show that people prefer living and shopping along tree-lined streets. No doubt, a big part of our collective appreciation of trees is their beauty. It’s hard to walk through a shady forest and not be captivated by the simple beauty it provides.

But trees don’t belong everywhere. Across the globe, vast swaths of the landscape are naturally treeless, and they make up 40% of all terrestrial ecosystems. They’re not barren landscapes, devoid of life. Rather, they’re some of our most productive and important ecosystems. These areas – known as grasslands, shrublands, prairies, steppes, pampas, or more generally, rangelands – are dominated by native grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs. They play a critical role in providing society with food and fiber, clean water supplies, and support a remarkable diversity of unique wildlife that don’t live in forests.

In the U.S., one-third of the country was once virtually treeless, including iconic regions like the Great Plains and sagebrush country in 13 western states. But these landscapes are changing. From Nebraska to Oregon, rangelands are slowly transitioning to woodlands, dominated by eastern redcedar, pinyon pine and juniper, Douglas fir, mesquite, and other trees. Of course, these tree species always existed adjacent to rangelands but were confined to higher elevations, fuel limited places, and along creeks and rivers where fire didn’t spread. As landscapes transition from rangeland to woodland, we stand to lose the critical services and values they provide.

For the last decade, the Sage Grouse Initiative has worked with private landowners, public land managers, and NGOs to help maintain and restore rangelands impacted by woodland expansion. This work, grounded in science and focused on improving priority wildlife habitat, has become a hallmark of our efforts in the West.

Highlighting the significance of this threat and sharing the science behind why removing encroaching trees is beneficial is also an important part of WLFW’s effort. To this end, WLFW partnered with a broad group to develop the Pinyon Juniper Encroachment Education Project.

We sat down with Jeremy Maestas, a sagebrush ecosystem specialist at the NRCS’ West National Technology Support Center in Oregon to learn more about the impact encroaching trees, and specifically the conifer trees that grow in the Intermountain West, are having on our sagebrush and grassland landscapes.

Can you tell us about the conifer expansion issue in the Intermountain West?

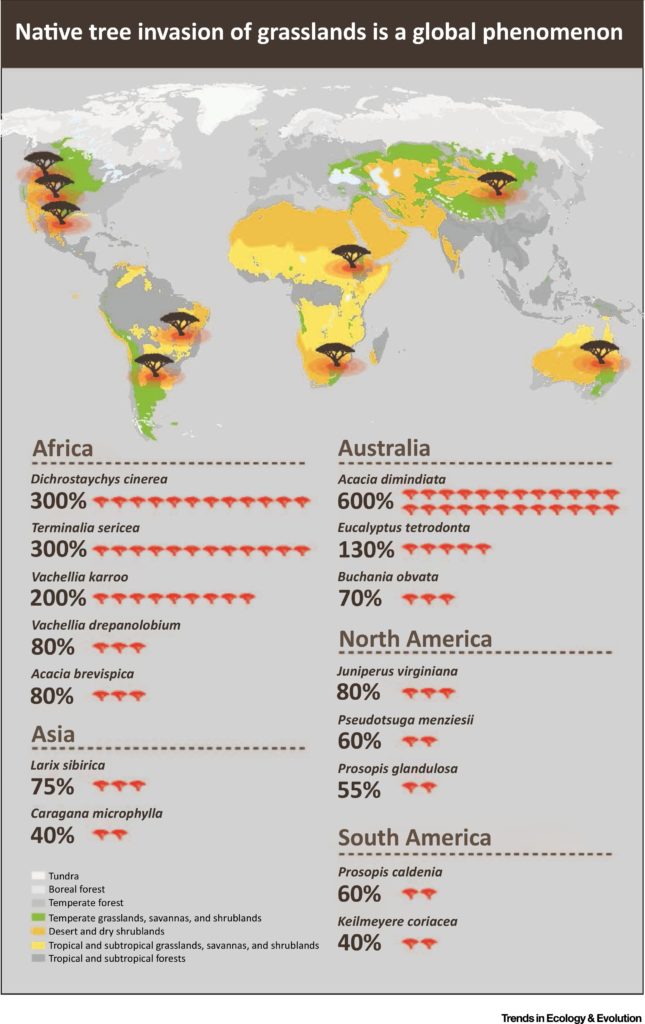

Sure. Extensive research shows us that native conifer trees, primarily juniper and pinyon pine, but also other conifers, have been increasing their footprint on the landscape at an unprecedented rate over the last 150 years or so, especially in places like the Great Basin. This is part of a global phenomenon of trees encroaching into and replacing adjacent grasslands and shrublands.

Some of that change is expansion in the traditional sense, that is, trees moving from higher elevations or fuel-limited sites protected from fire where they historically existed into areas where they never grew before. But much of the change is what we call ‘infill,’ which is what happens after trees colonize and continue to populate previously tree-less landscapes, turning them from sagebrush or grasslands with just a few trees per acre into closed-canopy woodlands – what you might think of as a forest.

I’ve always thought more trees is a good thing. Why is that not the case?

Trees are good! But context is everything. It’s important to acknowledge that pinyon-juniper woodlands and other conifer forests are incredibly important native ecosystems in their own right. They’ve been here for millennia and they provide valuable habitat and ecosystem services that are worth conserving too.

But, here’s the rub: their continued expansion is coming at a cost to imperiled ecosystems. In fact, 90% of tree expansion in the Intermountain West has occurred in sagebrush steppe – a habitat type that has already been reduced by half due to a wide variety of threats.

This transition from sagebrush and grassland ecosystems to woodlands and forests has consequences for things we care about as a society, such as, unique wildlife, functioning watersheds, and productive grazing lands. Species like sage grouse, found nowhere else in the world, are particularly sensitive to tall structures, like trees, and will abandon breeding habitats when there are just a few trees per acre. Conifer expansion also sucks up precious soil moisture needed on arid lands to grow other native plants, which means less food and cover not only for wildlife but livestock that sustain rural agricultural economies in the West.

What’s driving the expansion?

Unfortunately, the causes aren’t well understood but the evidence points to climate and reduced fire. The western U.S. experienced a favorable climate (cooler and wetter) in the late 1800s through the early 1900s that likely helped trees begin their accelerated march into new habitats. However, the effects of climate cannot be separated from other factors like Euro-American settlement and heavy livestock grazing of the region that occurred during the same time. The reduction of grasses through grazing is thought to have reduced natural wildfires. Later in the century, active fire suppression also allowed trees to expand and infill areas where they would have been burned historically.

What is being done to address this problem? Is it enough?

Land managers use a variety of techniques including mechanical tools, like chainsaws or heavy machinery, and prescribed fire to remove expanding conifers. While pinyon-juniper management has been occurring for decades for many different purposes, removal has really been ramped up in strategic places over the last decade to save sage grouse and sagebrush habitats. This has been a top priority for Sage Grouse Initiative partners on private and public lands in places like Oregon, Idaho, and Utah.

Your question about the scale of management is timely. We recently published a study that used satellite remote sensing data to quantify the extent of conifer reduction in sagebrush country. We found that total footprint of conifers in the region actually decreased by 1.6% over the last several years, with about two-thirds of that due to management and the other third due to wildfire. So, the short answer is we are making progress.

However, the sobering news is that researchers estimate pinyon-juniper trees continue increasing at a rate of between 0.4% and 1.5% annually. In the Great Basin alone, that has resulted in 1.1 million acres transitioning to forests since 2000, just 20 years. While the scale of conifer management may sound like a lot, it may just be keeping up with the current rate of expansion and infill. More needs to be done in priority watersheds.

What outcomes have you seen from this type of restoration work so far?

Well, thanks to some long-term research, we now know sage grouse are benefiting. A long-term study in Oregon showed that sage grouse population growth rates increased 12% following the strategic removal of conifer trees when compared to a nearby area where no trees were removed. This is one of the only habitat restoration techniques that has actually been scientifically proven to work for grouse, so these findings are huge.

Other sagebrush-dependent wildlife benefit as well. Studies have shown that in Colorado, mule deer fawn survival during the winter increased by 15% following conifer removal. The abundance of Brewers sparrow, a sagebrush-dependent songbird, doubled following conifer removal in another Oregon-based study.

Several other studies have shown two-to-twenty-fold increases in wildflowers and native grasses following conifer removal, improving forage for wildlife, pollinators, and livestock.

What’s the downside to removing conifer trees?

That’s a great question. For me, the effect of conifer removal (positive or negative) comes down mostly to where on the landscape the treatment is being done. In other words, it’s context dependent. There are some places, like in the middle of a historic pinyon-juniper woodland, where removing all the trees isn’t appropriate. That’s why we use what we call Ecological Site data, derived from the soils, to help tell us which sites were historically grasslands and shrublands versus woodlands and forests. Sage Grouse Initiative partners focus on removing encroaching conifer trees from former sagebrush sites in priority habitats for sage grouse. We work hard to ensure our treatments are highly targeted and designed to improve the health and resilience of places that used to be treeless sagebrush rangelands.

Obviously, there are a suite of wildlife that use, and depend on, conifer woodlands and forests so there is some concern about the impacts of removal on them. As you might expect, though, many of these species are also increasing as the footprint of trees grows. For example, many migratory songbirds that rely on pinyon-juniper woodlands, such as, the ash-throated flycatcher, juniper titmouse, gray vireo, and gray flycatcher, actually have stable-to-increasing population trends according to long-term monitoring data. One notable exception is the pinyon jay, which has experienced steep declines despite having more woodland habitat available. The causes of this are not well understood, but we suspect declines may be more related to the overall health and structure of historic pinyon-juniper stands than to the removal of trees from sagebrush habitats. Pinyon jay nesting is closely linked to the health of pinyon pine trees which has been declining as woodlands get thicker and suffer from prolonged drought.

The bottom line is that we need to take a holistic view the of landscape, from ridge top to valley bottom, in order to ensure restoration addresses the health of all lands including pinyon-juniper woodlands and forests. We’re not picking winners and losers; we’re just balancing the tables to ensure we don’t lose imperiled ecosystems and the species that rely on them.

Cheatgrass and other invasive annual grasses are also major threats to sagebrush country. Does removing conifer trees lead to cheatgrass invasion?

Unfortunately, cheatgrass is present throughout much of our sagebrush country and therefore is a new reality that must be considered in every management decision we make. Conifer removal doesn’t cause cheatgrass to invade, per se. Cheatgrass doesn’t just appear out of thin air. If cheatgrass increases following conifer removal, that’s because it was there before the conifers were removed. Like any vegetation, it’s simply taking advantage of the increases in sunlight, water and nutrients that stemmed from removing the conifers in the first place.

We know the risk of cheatgrass getting worse depends upon the site conditions, so we are using that knowledge to mitigate potential problems. For example, sites that are warmer and drier pose a higher risk. Also, maintaining healthy perennial bunchgrasses is key to resisting spread of cheatgrass. Managers use this information to plan follow-up weed control, seeding, and grazing management to keep invasive annuals at bay.

It’s important to note that doing nothing also poses risks. As shrublands transition to woodlands, fuel loads increase dramatically and perennial grasses decrease which sets us up for disaster when wildfire strikes. Hotter canopy fires in woodlands with a poor understory are ripe for wholesale cheatgrass conversion. Through conifer removal during early phases of woodland development, we’re actually trying to prevent a more catastrophic scenario from playing out.

What’s the most important thing you want readers to know about conifer removal in sagebrush country?

That’s easy: it works. It’s one of the few restoration practices for which we have the science showing a host of benefits, from water to wildlife. You can’t say that for some of the other restoration practices in sagebrush country. Do we need to continue monitoring and refining our treatments? Absolutely. But the weight of evidence suggests this is an important practice if we’re going to maintain sagebrush habitats that are under threat from many factors.

I’d also say this isn’t just a problem in the past. Conifer encroachment continues today, as shown by the satellite data. Conservation partners are going to need to band together in priority watersheds and accelerate management in order to get ahead of the rate of expansion and infill.

Keep in mind that this also isn’t just a local problem; it’s part of a larger phenomenon impacting grasslands and shrublands around the world. It’s easy to underestimate the scale of change and impacts of conifer encroachment, but the consequences are truly on par with human-caused losses of rangelands like cropland conversion and development.

CHECK OUT THE PINYON JUNIPER ENCROACHMENT EDUCATION PROJECT WEBSITE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT IMPACTS, READ SUCCESS STORIES, FIND PEER-REVIEWED SCIENCE AND MORE…

Meet the expert

What’s your favorite part of your job?

Knowing that the work we do matters. It’s a powerful thing to find a career you truly love! I work

with amazing people who are passionate about making a difference for people and the land, which is inspiring every day.

What’s your favorite weekend activity?

Well, I live in beervana here in central Oregon so weekends typically involve some kind of outdoor activity with my wife, Kindra, and three kids (Jake, Kaitlyn, and Jadyn) followed by some craft brews.

Who is your conservation hero?

From a historical perspective, hands down it’s Teddy Roosevelt. Talk about a guy who did hard things to usher in the era of conservation in America. In a more contemporary sense, my heroes are all those unsung rockstars I work with, from ranchers to range cons, who quietly make conservation happen every day on the land.

For more information on conifer removal and for citations to the research referenced in this Ask an Expert, see this Frequently Asked Questions About Conifer Removal in Sagebrush Country, developed by the WLFW-Sage Grouse Initiative, the Intermountain West Joint Venture, the Great Basin Fire Science Exchange and The Nature Conservancy in Montana.

For a recent review of the science, see the Conifer Expansion chapter (Chapter M) in the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Sagebrush Conservation Strategy.