Study Demonstrates Importance of Voluntary Conservation for Grassland Birds

Study highlights how voluntary conservation protected habitat for 4.5 million grassland songbirds, and boosted populations by 1.8 million birds!

Ask an Expert | The Green Glacier: What is Conifer Encroachment and Why is it Bad?

June 22, 2021

Turning former cropland into green grass — and green cash

July 12, 2021

Three of the vulnerable grassland bird species that benefit from voluntary conservation. Left to right, Grasshopper sparrow by Alan Schmierer; Lark bunting by Tom Benson; Cassin’s sparrow by Alan Schmierer.

Voluntary grassland conservation in the Great Plains conserves habitat for 4.5 million grassland songbirds, including eight imperiled species, and helps populations of some of the most vulnerable birds exceed recovery goals.

The trill of an Eastern meadowlark singing his springtime song is unmistakable. Flute-like, the series of gentle notes drift across the southern prairie. With his yellow breast popping, the meadowlark rises his beak to the cobalt sky, and buzzing insects, rustling grasses, and mooing cows add their voices to the chorus.

Eastern meadowlark. Photo by John Sutton.

Sonic scenes like this are more common across the Great Plains, thanks in part to forward-looking landowners who have partnered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to preserve and maintain privately owned agricultural lands, according to new research published in Conservation Biology by Dr. David Pavlacky, biometrician with Bird Conservancy of the Rockies.

Dr. Pavlacky investigated how the USDA’s incentive-based, voluntary conservation approaches benefitted grassland-dependent bird populations. The paper, “Scaling up private land conservation to meet recovery goals for grassland birds” highlights that private land conservation provides a solution to declining bird populations in North America and scales-up to meet population recovery goals for the most imperiled grassland birds.

Populations of grassland songbird species – including the Eastern meadowlark, lesser and greater prairie-chicken, lark bunting, and Cassin’s and grasshopper sparrows – have declined significantly over time due to a variety of land-use conversions and habitat fragmentation and degradation.

Lesser prairie-chicken (photo Jeremy Roberts, Conservation Media)

Because nearly 95 percent of grasslands in the Great Plains are privately owned, voluntary conservation that improves the health and resiliency of grasslands from North Dakota to Texas is essential to reversing these declines. The USDA provides support in this effort through the Farm Service Agency’s (USDA-FSA) Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (USDA-NRCS) Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI), both funded through the Farm Bill.

CRP provides set-aside payments which incentivize landowners to restore grasslands by planting native or introduced grasses and legumes on former cropland. Landowners enroll their land in CRP for 10-15 years, replant to grassland, and manage it as grassland for the length of the contract.

Through LPCI, landowners receive technical and financial assistance from USDA-NRCS to implement prescribed grazing and other conservation practices that mutually benefit wildlife habitat and ranch productivity.

From 2015-2017, Dr. Pavlacky and his team evaluated if these conservation measures had meaningful effects on grassland bird populations. The study focused on ranches in Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas. The researchers compared avian population densities on reference grasslands to privately owned ranches enrolled in CRP or that had prescribed grazing plans in place through LPCI. Additionally, they quantified vegetation within a 50-meter radius of each bird point count location to study habitat relationships.

What the researchers found is heartening for bird nerds and agricultural producers alike.

The research highlighted the critical role working agricultural lands play in recovering imperiled wildlife populations and the potential for conserving habitat on a large scale. In the paper, Dr. Pavlacky noted, “Our results suggested voluntary conservation programs addressing landowner interests scaled-up to meet the population recovery goals for the most imperiled grassland birds of conservation concern.”

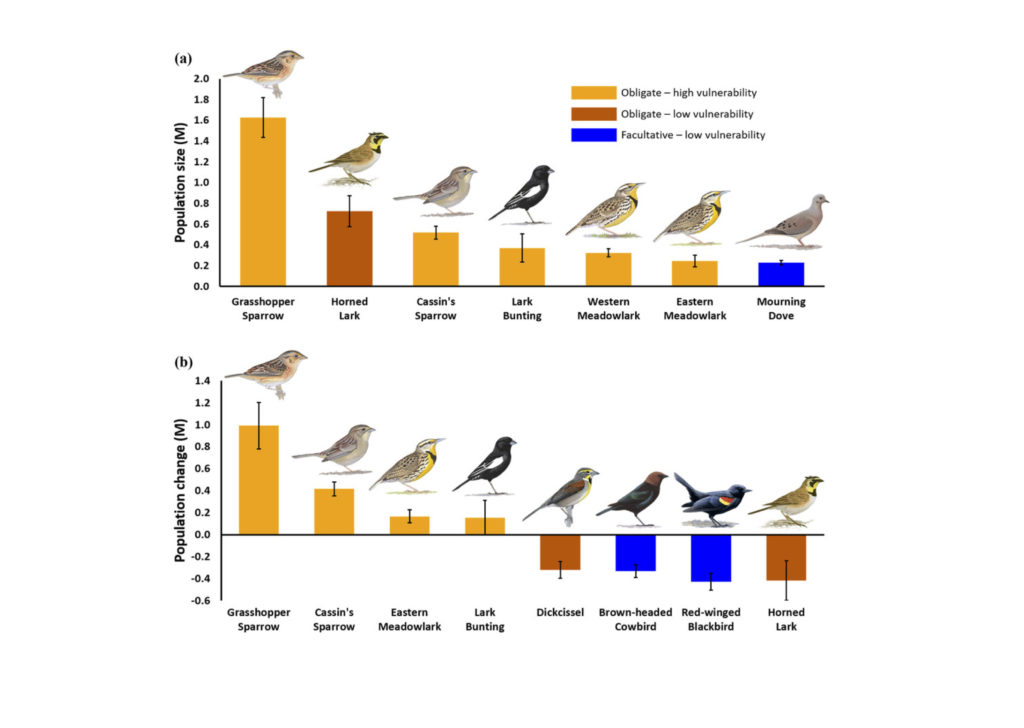

The study showed that population increases for the most vulnerable grassland-dependent bird species met or exceeded recovery goals set by the Partners in Flight network, a group of more than 150 different organizations working to maintain and restore North America’s bird populations.

Researchers found these voluntary, incentive-based conservation practices conserved breeding habitat for at least 4.5 million grassland songbirds. Furthermore, the populations of many of these species increased by 1.8 million birds during the study period.

The study also found ranches that implemented prescribed grazing through LPCI showed the greatest variety and abundance of some of the most vulnerable grassland-dependent birds in the Great Plains like grasshopper and Cassin’s sparrows, lark bunting, and the eastern meadowlark. These ranches had taller shrubs and grasses than reference grasslands, showing how healthy vegetation helps increase the biodiversity of grassland birds.

Estimated overall (a) population size for land enrolled in conservation practices and (b) population change from treatment effects relative to reference strata for grassland birds by grassland specialization and Partners in Flight breeding-season vulnerability in Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas, 2016 (error bars, SE). Image courtesy of David Pavlacky. Click image to see full study.

Dr. Pavlacky’s team also found that CRP-enrolled ranches boosted songbird abundance, attracting an array of grassland-dependent and generalist species. Importantly, CRP-enrolled lands provide additional benefits beyond habitat for imperiled grassland-dependent songbirds, including reduced soil erosion and improved water quality. CRP-enrolled lands also store carbon underground, adding yet another benefit to expanding native grasslands. Helping willing producers transition their expiring CRP fields into valued grazing lands, as opposed to replanting them back to crops, is another innovative way to keep grasslands intact for wildlife and agriculture.

Overall, grazing management and expanding grassland acreage through CRP both had substantial impacts on the most imperiled songbirds in North America. This outcome suggests that scaling up private land conservation that links social and natural systems through incentive-based conservation can simultaneously address ecological threats and improve human well-being. As Dr. Pavlacky noted, “A similar investment in private land conservation in the study area over a period of 50 years is projected to conserve breeding habitat for 200 – 255 million birds.”

This research would have been impossible without landowner participation, specifically allowing researchers onto their ground over an extended period. The co-production of science is critical to evaluating the effectiveness of these and other Farm Bill-funded conservation practices. It also provides a foundation for a shared commitment to conservation between landowners, federal agencies, scientists, and land managers. Funding for the study came from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the USDA-FSA and USDA-NRCS.

As policymakers, conservationists, and federal agencies focus on reversing the long-term declines in grassland bird populations, this research demonstrates how successful, incentive-based programs are a win-win for wildlife and landowners. And that is something to sing about!

>>Read the complete paper in Conservation Biology here<<

>>Learn more about this study in this Science to Solutions post<<