Building Bridges | Ranchers Are Stewards of the Land

In recent years, a new appreciation is taking hold in the West about the role and benefits of sustainable ranching. The article below captures the essence of why we believe that sage grouse conservation is best achieved through working cooperatively on private lands

Ranchers and Conservationists Combine to Help Sage Grouse

September 18, 2015New Study Affirms Lesser Prairie-Chicken Research Practices

September 20, 2015

In recent years, a new appreciation is taking hold in the West about the role and benefits of sustainable ranching. The article below captures the essence of why we believe that sage grouse conservation is best achieved through working cooperatively on private lands, and partnering closely with the people who manage them. The following piece was written by Andy Rieber, and published in the American Cowboy magazine.

—

Some fashions are better off dead. Few, I imagine, would wish back the days of stifling whalebone corsets or immobilizing floor-length skirts. The same principle of progress should hold true not only of what we wear, but also of what we think. Simply put, when ideas persist beyond function or sense, they too should be cast off. Case in point: the threadbare contention that ranching and conservation are incompatible.

For years, it was fashionable among environmental activists to revile cattle grazing as the root cause of all evils (real and perceived) on our Western rangelands. Cattle overgrazed. Cattle destroyed wildlife habitat. Cattle made deserts out of grasslands. Cattle were causing the atmosphere to warm and the seas to rise. There was no logical way—so the narrative went—for a conscientious person to support ranching and the culture of the American cowboy while at the same time being a friend of the earth.

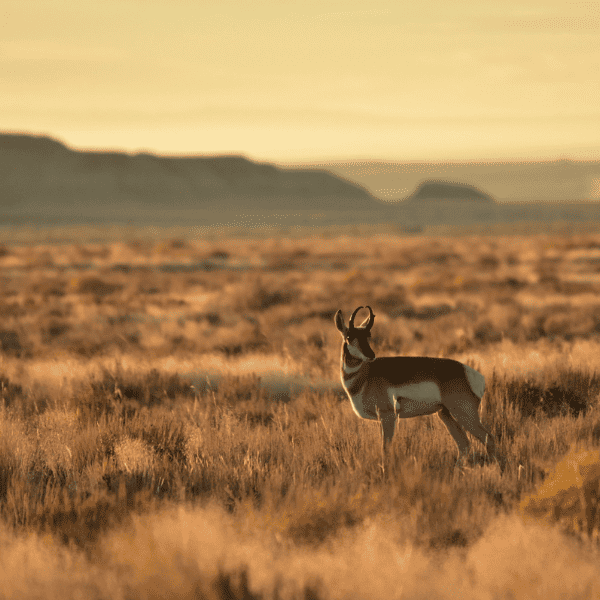

But how times do change. Recently, a new awareness has emerged among conservationists, scientists, and land managers that the benefits of grazing—not to mention the custodianship ranchers bring to the great open spaces—are invaluable for conserving healthy landscapes. At the center of the ranching-conservation movement is the West-wide effort to protect the Greater Sage Grouse, which is being considered this September for a listing under the Endangered Species Act. Throughout the 11 Western states where this low-flying bird is found, ranchers are lining up to participate in efforts to protect the Greater Sage Grouse, whether through conservation easements, cooperative management agreements, landscape maintenance, or grazing modification. In partnership with the USDA’s Sage Grouse Initiative, 1,129 Western ranchers have, to date, conserved 4.4 million acres of Greater Sage Grouse habitat.

What many ranchers have known for generations—that well-managed grazing is a benefit to rangelands—is finally getting recognition, not least of all from the Secretary of the Interior, Sally Jewel, who has personally visited ranches across the West to see firsthand how ranchers are leading the Sage Grouse conservation charge. But the ranching-conservation story goes well beyond the race to save a single species. With no fanfare and little thought of recognition, ranchers today are quietly restoring watersheds, improving wildlife habitat, fighting range fires, and preserving some of the last great open spaces on the American landscape from developers’ hungry Caterpillar earth movers, oftentimes in partnership with groups—like the Nature Conservancy or the Audubon Society—whose view of ranching has measurably evolved.

The perceived divide between ranching and conservation is closing. For those of us who relish the beauty, raw intensity, and historical relevance of cowboy culture, this new appreciation of ranching should be immensely gratifying. Why? Because ranching is the taproot of American cowboy culture—working ranchers and cowboys, both men and women, of yesterday and today, are the creative source and inspiration for the music, art, craftwork, and film depicted in American Cowboy. But America’s ranchers are not simply the bearers of a culture worth celebrating. They as an industry, and as a community of people, are custodians of the sweeping natural open spaces that are the very essence of the American experience. Their dedication to conserving these landscapes warrants more than appreciation. It calls for our unequivocal support.

Andy Rieber is a freelance writer living in remote Adel, Oregon. Her writing has been published in the Wall Street Journal, Wired, the Western Livestock Journal, Working Ranch, Jefferson Monthly, and the Oregon Beef Producer. Visit her website at andyrieber.com.