Landscape Explorer map shows how much the West has changed since the 1950s

Explore past and present landscapes from the Great Plains to the Pacific coast. New, easy-to-use map uses historic and current aerial imagery to highlight how our landscapes have changed since the mid-20th century and how we can conserve our natural heritage.

USDA Announces Historic Investment in Wildlife Conservation, Expands Partnership to Include Additional Programs

June 27, 2023

New “Pocket Guide” Provides Unified Planning Process for Reducing Woody Encroachment in Grasslands

July 18, 2023Landscape Explorer is a new, interactive map application that shows historic and current imagery from the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast, allowing anyone to quickly visualize threats to these landscapes.

Do you know what your neighborhood looked like 70 years ago? How about your favorite open space, local hills or nearby river valleys? Now you can instantly see how landscapes across the American West have changed over the past half-century with the Landscape Explorer.

This brand-new free online map application displays past and present aerial imagery across 17 western states. An easy-to-use slider seamlessly toggles between historic and current imagery in a Google-powered map. In just a few seconds, anyone can zoom in to see the changes anywhere across the West – a ranch, a town, a major city, or an entire region – then zoom out to visualize what’s changed across an entire state.

“The Landscape Explorer puts cutting-edge technology at the public’s fingertips so we can work together to conserve our rangelands,” says Scott Morford, a researcher at University of Montana’s Numerical Terradynamic Simulation Group who led the development of the Landscape Explorer.

Western grasslands and shrublands provide our country with food, fiber, recreation opportunities and wildlife habitat. But they are at risk of disappearing. This interactive new map clearly shows how and where three main threats have altered these imperiled landscapes since the 1950s: woody encroachment, cropland expansion, and urbanization.

The mapping tool was co-produced by scientists at the University of Montana in partnership with the USDA-NRCS’ Working Lands for Wildlife, Montana NRCS, Intermountain West Joint Venture, and NVIDIA. First, the collaborative team compiled historic imagery collected by the U.S. Army and archived by the U.S. Geological Society as well as from state databases. These historic images were collected between 1940-1970, but most are from the 1950s. The modern aerial imagery was provided by Google and was collected between 2014-2023.

Next, the science team used specialized software to process the historic imagery and stitch together adjacent aerial images to create a continuous mosaic from the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast (the coast will be completed by September 2023). When the Landscape Explorer is zoomed in, users can click on the historic imagery to see when it was taken and who took it. The map also allows you to download images or export them as GIS data—all for free.

“We don’t always notice what’s unfolding on the land over longer timespans, especially when environmental changes are slow-moving,” Morford notes.

This is especially true for places where grasslands have gradually transitioned to woodlands in the absence of regular fires. On prairies that were historically tree-free, the steady creep of conifers onto grasslands leaves less forage for livestock, degrades wildlife habitat, and also reduces the water in streams.

With the Landscape Explorer, landowners can see where these changes are happening and better target where to remove encroaching trees to save their grasslands. In Nebraska’s Loess Canyons, for instance, ranchers have deep local knowledge of how trees have changed the land over the past few generations. Innovative mapping tools are helping these landowners and other local groups throughout the Great Plains to proactively manage woody encroachment and restore productive pastures.

Comparing historic and current aerial imagery also shows another obvious and worrisome transformation—vast swaths of our grasslands and sagebrush have been plowed up and converted into annual row crops. When native plants are tilled under to make way for water-hungry crops, we lose fertile soils, valuable wetlands, and wildlife habitat.

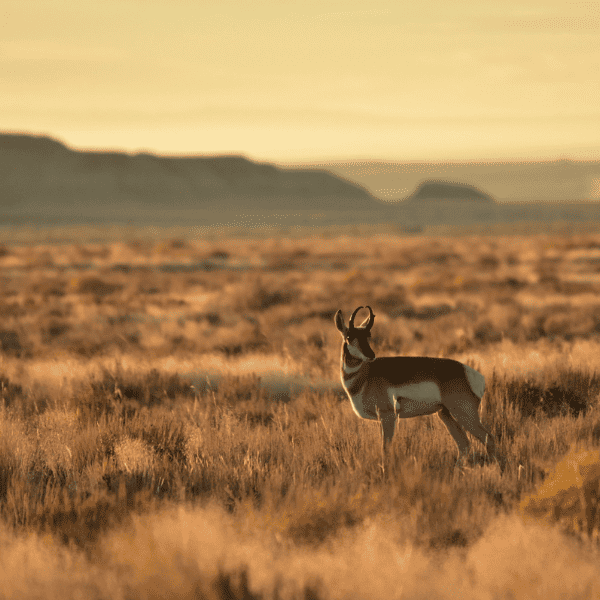

The Landscape Explorer shows where remaining native rangelands are at risk of being plowed up, helping managers prioritize at-risk areas where conservation easements or other tools can help keep native rangelands intact and resilient. For example, in northern Montana Kelly and Tami Burke switched to no-till farming and took advantage of cost-share programs to replant cultivated farmland with native grasses. Not only are their cattle healthier and their ranch more profitable, the land better supports sage grouse, songbirds, and pronghorn.

This new mapping tool also shows how fast-moving changes like industrial or suburban development can rapidly transform native rangelands. Zoom in on Las Vegas, Nevada or Fort Collins, Colorado, and you’ll see how wide-open working sagebrush lands have been gobbled up by concrete and asphalt. While urbanization is a localized threat in the West, it’s one of the most severe—it squeezes out agricultural landowners and destroys wildlife habitat.

Luckily, the Landscape Explorer can also quickly and easily pinpoint the remaining intact landscapes, allowing landowners and local managers to maintain them for future generations. In northwestern Colorado, an NRCS-funded conservation easement protected the Etchart family‘s prime working ranch from development. The family conserved their livestock hay ground while also benefiting the elk and mule deer that roam through their fields.

The ways to use the new Landscape Explorer are as varied as the landscapes it displays. “Knowledge is power, and this new tool puts both into the hands of landowners, scientists, and citizens,” says David Naugle, science advisor for Working Lands for Wildlife. “Seeing exactly what’s changed over time will inspire more people to work together to conserve the beautiful and valuable landscapes of the western U.S.”