Ask an Expert | The Science Behind Private Lands Conservation: A Conversation with Dr. David Naugle, Working Lands for Wildlife Science Advisor

Learn more about WLFW’s approach to science, how the coproduction of science benefits private-lands conservation and what’s next for the Western WLFW science team.

Nature’s Engineers: How Beavers Boost Streamflows and Restore Habitat

January 13, 2020PHEASANTS FOREVER Magazine | Of Partners, Promises and Prairie Treasures – LPCI

February 13, 2020

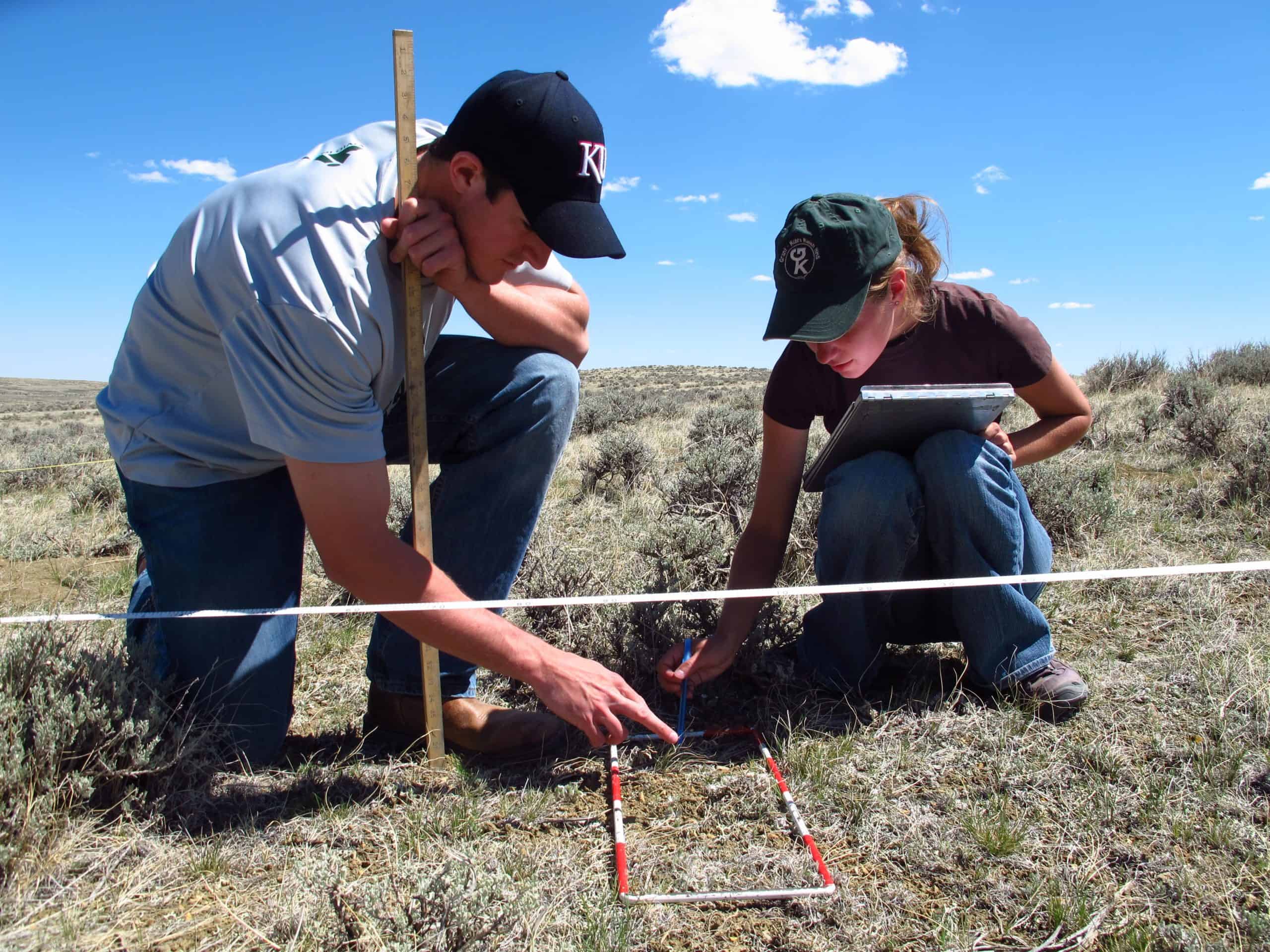

New findings show that it’s more accurate to measure grass height for all nests – failed or hatched – at the predicted hatch date. Photo: Joe Smith

What is the coproduction of science? How important is science to WLFW’s conservation effortd? This Ask an Expert has the answers.

The Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI) is part of the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Working Lands for Wildlife efforts – nationwide initiatives focused on conserving and restoring working agricultural lands to benefit wildlife and watersheds while also improving ranch and farm productivity. SGI’s decade-long, shared vision is “wildlife conservation through sustainable ranching.”

SGI, now part of the Working Lands for Wildlife suite of initiatives, takes a team approach to conserving western rangelands: NRCS leadership ensures Farm Bill funding is used efficiently and effectively to improve western rangelands for healthy wildlife, water, air and plants, and for the rural communities they support. Local NRCS staff and the Strategic Watershed Action Team (SWAT) work with private landowners to implement conservation practices like sustainable grazing systems, mesic habitat restoration, conifer removal and prescribed fire. Partners, like Pheasants Forever and The Nature Conservancy, leverage funding and resources to do more work across the West. It’s a great model that has allowed WLFW to work with more than 2,000 ranchers and to conserve almost 8 million acres of western rangeland since 2010.

But there’s another group of people behind the scenes who play an integral role in WLFW’s work: A team of working lands scientists. Since its inception, WLFW has been a science-driven effort.

Long-time Working Lands Science Advisor and University of Montana wildlife professor, Dr. David Naugle, leads the SGI’s science team. Dr. Naugle recently published a paper in the prestigious journal BioScience entitled Coproducing Science to Inform Working Lands: The Next Frontier in Nature Conservation. This new paper champions both the importance of working lands in conservation and the role for science in achieving better outcomes for ranching and wildlife.

We sat down with Dave to learn more about the critical role science plays in our approach to conservation.

Why your intense interest in working lands conservation?

I spent my early career working on public lands policy but now find myself fascinated by working rangelands as global productivity centers, biodiversity hotspots, and the glue that holds together public lands. The father of modern conservation, Aldo Leopold, taught us that “conservation ultimately boils down to rewarding the private landowner who conserves the public interest.”

Public lands are a cornerstone of American culture but it’s the privately owned working lands that hold the key to maintaining conservation-reliant species for which persistent threats cannot be eliminated but only actively managed. Reinvesting in these rural communities is the best way I know to keep intact grazing lands from being swallowed up by cultivation, subdivision and energy developments.

Your paper is called Coproducing Science to Inform Working Lands: The Next Frontier in Nature Conservation. What is coproduction and how does it differ from other approaches to science?

Simply put, coproduction of knowledge is a way of making science more actionable by engaging with stakeholders to share in both study design and implementation. And surprise, surprise…people are more apt to incorporate new information into their way of thinking if they are invested upfront in its production. So, the goal of coproduction is to achieve better outcomes for society by engaging more people earlier in the science process and thereby increasing the utility of science in decision-making and practice.

Notably, the recent popularity of coproduction in health care with patient and public involvement is leading to better outcomes. If widely adopted for working lands, coproduction could provide participants with the necessary knowledge to better sustain rural livelihoods and nature’s resources on privately managed rangelands, forests, and cultivated lands that collectively occupy 80% of the world’s terrestrial area.

Outcomes are all the rage today in conservation; what is an outcome?

Merriam’s dictionary defines outcomes as: “something that follows as a result or consequence.” In other words, an outcome is the upshot, or the way a story turns out. In contrast, outputs simply describe the amount of conservation produced, which are typically reported as acres enrolled, miles managed, or dollars allocated. Outcomes are superior to outputs because they quantify the impact of conservation efforts.

For example, WLFW’s efforts have resulted in the following outputs: 11,000 square miles of sagebrush grazing lands restored or enhanced on more than 2,000 ranches since 2010. While such outputs are large, even more impressive are resulting outcomes including +12% higher sage grouse population growth within conifer management in Oregon, +25% greater vegetation productivity for ranching and wildlife following riparian and wet meadow restorations in Nevada, Oregon and Colorado, and 75% of priority habitats conserved for two migratory mule deer herds through measures enacted to protect sage grouse in Wyoming.

If I’ve learned anything over the years it’s this…having coproduced outcomes makes it way easier to tell your conservation story. Outcomes also provide partnerships with a mechanism for sustained funding by articulating return on investment to stakeholders. Looking back, the 2015 ESA decision was a major testing ground for the utility of outcomes in evidence-based conservation. Turns out the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service cited SGI outcomes 43 times in their determination to not list sage grouse as an endangered species.

Has your coproduced science ever failed to support a highly anticipated outcome?

Oh, yeah, it really happens. Such was the case when a seven-year assessment showed that pastures rested from domestic grazing did not increase sage grouse nest success. Despite dogmatic support in the literature, the hypothesized benefits of herbaceous hiding cover never materialized at pasture- and ranch-level scales in which herbaceous cover was experimentally manipulated. In response to our findings, the NRCS adjusted delivery of conservation practices to de-emphasize financial incentives being paid for extended rest within rotational grazing systems.

These results spawned additional inquiry challenging the long-held belief that grazing restrictions inevitably benefit sage grouse populations. Follow-up study revealed that commonly used methodologies were inherently biased, misrepresenting the relationships between habitat structure and sage grouse nest success. These results initiated a third line of questioning to understand the economic implications of the unintended habitat loss on private land resulting from grazing restrictions placed on publicly adjacent rangelands. Collectively, this string of coproduced science is raising the collective appreciation of the more complex interrelationships between wildlife habitat and ranching enterprises in this public–private checkerboard of land ownership of the Western U.S.

Why is Working Lands for Wildlife science unique?

Unique maybe; laser-focused…always! As the science arm of WLFW, we do two things— 1) develop spatial targeting tools to pinpoint where to invest in conservation, and 2) evaluate whether resulting investments yield desired outcomes. The USDA and our partners know that limited resources necessitate a strategic, landscape-scale approach that replaces random acts of conservation kindness to increase the odds of achieving desired outcomes.

Versed in coproduction, our science team knows well the painstaking preplanning and delayed gratification that accompanies doing science alongside real, watershed-scale conservation. We often jest that science chases implementation because of our partners’ appetites for access to coproduced science, online tools and additional outcome-based evaluations. For example, it took us ten years, two PhD students and a boatload of radio-marked birds to confidently say that conifer management increases sage grouse population growth by +12%. From a science perspective, quantifying this level of population response is almost unheard of in wildlife management, and I hope this new knowledge gives managers the confidence to continually scale up this beneficial practice. Is it easy? No. Is it worthwhile? Absolutely.

What do you value most with your involvement with working lands science?

We science folks can be a flighty bunch, chasing personal research interests and jumping from one funding opportunity to the next. But I’m a long-term investor who believes that it takes time to develop a meaningful program. The tendency for science to be paid for and published, but then left on the shelf for someone else to find and use is no longer a defensible approach. To quote Wes Burger, a private lands scholar and colleague at Mississippi State University: “science should be done with the intent to deliver conservation actions, and delivery should be done with the intent to measure outcomes.”

Also, and this aligns with the concept of coproduction, the WLFW team does a good job of making all the science we produce accessible to multiple audiences. A recent report from the University of Wyoming’s Ruckleshaus Institute titled “Developing a social science research agenda to guide managers in sagebrush ecosystems (2019)” noted: “One communication model highlighted by multiple participants is the Sage Grouse Initiative’s (SGI) Science to Solutions program, which multiple participants felt was an effective strategy for reaching a diverse array of stakeholders.” I think that’s pretty great. That same report also stated that, “Participants emphasized the importance of trust and relationship building on behalf of social scientists and decision makers and identified the Sage Grouse Initiative as an example of a trusted source of information that has had some success in influencing sagebrush conservation and management decision making.”

So, if I had to put my finger on one thing that makes Working Lands for Wildlife special, it’s the direct pipeline between science and conservation. The speed at which new knowledge is incorporated into on-the-ground conservation is amazing; once you experience this as an applied scientist you’ll never go back!

Where is the science arm of WLFW headed next?

We’re diving headfirst into expanding conservation using our new Rangeland Analysis Platform or RAP. The RAP is the brainchild of Brady Allred our rangeland ecologist here at University of Montana. It fits our philosophy wherein coproducing scientists provide partners with state-of-the-art mapping technologies who, in turn, implement well-placed practices to further scale up beneficial outcomes.

And as word spreads, neighboring watersheds are hungry to employ this tool (and others) in their backyards. Idaho is using RAP-based invasive annuals mapping to craft their Cheatgrass Challenge knowing that weed control is most effective when management is informed by what’s going on in the surrounding landscape. On the horizon for the RAP are jam sessions with USDA to evaluate pipelines for these web applications to be used more broadly across the Department.

Lastly, the upcoming launch of our newest RAP functionality will evaluate biological and economic strategies to help partners get ahead of woodland expansion on grazing lands across the western U.S.

Does your crystal ball show a bright future for working lands conservation?

There is no doubt in my mind that we are entering a ‘Renaissance-type Era’ for private lands conservation that will rival our response to the Dust Bowl. Landowner-led and collaborative partnerships will show us the way with much leadership already in place (e.g., Blackfoot Challenge, Malpai Borderlands Group, Tallgrass Legacy Alliance, Sandhills Task Force, and many more). Local landowner leaders hold much of the deeply rooted trust and credibility necessary for the longevity of resulting conservation.

Equally important is the advancement of like-minded, landowner-led groups such as Western Landowners Alliance and Partners for Conservation that are coalescing into umbrella organizations to extend their shared vision of working lands conservation into additional watersheds. The only real question now is one of further coordination and support so that we’re all pulling in the same direction.

Any closing thoughts beyond coproduction?

Yeah I have one that keeps me up at night…as conservation professionals we ought to ask ourselves if we’re properly equipping the next generation in working lands conservation. The public recognizes the Farm Bill as one of the most globally powerful tools in conservation. Neighboring countries envy us for it, yet its depths are poorly understood locally, and unknown to most of the generation in training.

I often play the acronym game with wildlife students in class; they all know BLM, FWS and USFS, but most blankly stare back when I quiz them on NRCS. We need to change that to effectively deliver conservation on private lands at watershed scales.

But even when I start to worry, I’m reminded of rapid change on this front too. For example, Lowell Baier’s new book entitled Saving Species on Private Lands, due out in April, serves as a Farm Bill roadmap for landowners, and as a first to my knowledge, Colorado State University is advertising a Professor of Working Lands position.

Meet the Expert

What book are you currently reading?

Don’t be Such a Scientist (2018) by Randy Olson, and anything else I can get my hands on to make me a better communicator with non-science audiences—have to admit, I’ve become a bit obsessed the last couple of years.

What is your favorite non-academic activity?

Family, family, family. Travel hockey with our son is the focus for weekends now through March. I’m having a blast watching my daughter finish up undergraduate here at UM before heading to PA school next year. My wife and I are travel junkies that love investigating different corners of the world—next up, Norwegian fjords.

And finally, you got your MS and PhD from South Dakota State but now work at the University of Montana. Who do you root for?

Oh gosh…ok, picture this, how about a ‘Go Griz’ hoodie overtop my ‘Get Jacked’ SDSU t-shirt on game day when Jacks battle Griz on the gridiron in UM’s Washington-Grizzly stadium!