FAIR CHASE Magazine | The Value of Sagebrush Country

by Josh Millspaugh | This feature in the December 2017 issue of Fair Chase Magazine highlights how sage grouse conservation benefits hunters and a host of wildlife species.

Sage Whiz Quiz | How Do Sagebrush Animals Survive Winter?

December 6, 2017

Bats, Butterflies, Bobwhites and More! New Videos About Working Lands For Wildlife

December 19, 2017

Download the original magazine article

By Joshua Millspaugh, Boone and Crockett Professor of Wildlife Conservation, W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation at the University of Montana

Surprise in the Sagebrush

Stalking through the sage, I heard a sparrow trill as dawn pinkened the horizon. The pronghorn was grazing on waving bunchgrass as I lifted my rifle. Crack! He fell after a single leap. I inhaled the sharp, clean scent of sagebrush as I knelt beside the antelope, appreciative of the wide-open rangeland that fed this animal that would now feed me.

Stalking through the sage, I heard a sparrow trill as dawn pinkened the horizon. The pronghorn was grazing on waving bunchgrass as I lifted my rifle. Crack! He fell after a single leap. I inhaled the sharp, clean scent of sagebrush as I knelt beside the antelope, appreciative of the wide-open rangeland that fed this animal that would now feed me.

After growing up in the forests of upstate New York, my first impression of the West’s vast sea of sage was “monotonous.” It’s proven me wrong again and again.

What looks homogenous at first glance is actually filled with extraordinary wildflowers, lush riparian areas, and all sorts of wildlife species that are uniquely adapted to live in a harsh, open environment. My favorite part about sagebrush country is the surprising diversity of animals and plants that live there. The more I’ve learned about this dynamic and diverse ecosystem, the more I’ve come to value it—both as a hunter and as a scientist.

The American West’s sagebrush range provides some of the best hunting grounds in the world. Spanning 13 western states, this ecosystem shelters and feeds pronghorn, mule deer, elk, and a host of upland birds. It also supports thousands of working ranches and hundreds of rural communities.

I’ve conducted wildlife research in many parts of the United States and in several places in South Africa, and can vouch for the fact that the sagebrush sea is special. I first spent significant time out West while researching elk in the Black Hills region of South Dakota—close to where I shot the pronghorn. After that, I came to know sagebrush ecosystems while overseeing a sage grouse research project that took place on a vast private ranch in southcentral Wyoming.

I distinctly remember having lunch one day in the field after tracking sage grouse that morning. We were hunkered in a small aspen grove to catch a break from the high-elevation sun. All of the sudden, I saw movement out of the corner of my eye—an elk! It was an unexpected encounter, as I hadn’t considered seeing elk in this very small patch of forest surrounded by sage.

But like 350 other species, elk rely on sagebrush habitat, especially during the winter months when they seek out nutritious sage leaves and other easy-to-access forage on the range. Given 40% of sage grouse range overlaps with elk range, it made sense that we saw elk while searching for the West’s iconic upland bird.

The Biggest Upland Bird

A greater sage-grouse displays. Photo: USFWS

I’ve had a soft spot for upland birds ever since I was a young boy, when I hunted pheasants and ruffed grouse with my family. In particular, I’ve always been fascinated by the elaborate mating rituals of grouse species. Communal lekking is one of the most interesting behaviors in the animal world.

Needless to say, I was excited to lead a long-term study researching the largest—and most famous—upland bird in the nation: the greater sage-grouse.

The first time I held a sage grouse, I was blown away: it was bigger than I’d imagined. I was driving across the ranch on an ATV one night with my graduate student and research assistant, searching for a sage grouse to tag. The Wyoming sky was bright with stars above us, and our spotlight uncovered all sorts of nocturnal critters amidst the sage.

We finally found one, capturing the wily bird in a hoop-net. Since I’d mainly worked with mammals, putting the small GPS transmitter on the hen was trickier than expected, to say the least. She was quite an armful!

Over the next six years, I oversaw two graduate student projects researching different aspects of greater sage-grouse ecology and management on the ranch. The goal of this year-round study—which was a partnership between private industry, state and federal agencies, non-government organizations, and a university —was to establish comprehensive baseline information about the bird before a wind energy project was constructed in order to better evaluate potential impacts post-construction.

In the summer, we measured the type of vegetation used by sage grouse, and also followed broods and monitored chick survival. In the winter, we relied on satellites or fly-overs to track the birds’ movements and survival rate. And in the spring, we monitored attendance on mating leks, as well as the males’ movements among leks.

I grew more and more impressed by the birds’ ability to make a living in such an extreme environment where it’s hot in summer, frigid in winter, wide open, and hard to raise young. As if that isn’t enough, sagebrush-dependent wildlife face a bigger risk: the loss of their habitat.

Saving Sagebrush Range

The once-vast sagebrush sea is getting chopped up by invasive weeds, energy and housing developments, cropland conversion, encroaching conifers, and more extreme wildfires.

The once-vast sagebrush sea is getting chopped up by invasive weeds, energy and housing developments, cropland conversion, encroaching conifers, and more extreme wildfires.

Sage grouse are the ‘canary in the coal mine’ that herald how this vital ecosystem is faring. These birds rely entirely on sagebrush-dominated landscapes: it’s their primary food source, their breeding grounds, their chick-rearing sites, their safe zones from hungry predators.

Unfortunately, sage grouse populations have dwindled to ten percent of their historic numbers. This decline led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to add the greater sage-grouse to its “Candidate List” in 2010 for potential listing under the federal Endangered Species Act. That same year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service launched the Sage Grouse Initiative to focus Farm Bill resources on voluntary, proactive conservation on private agricultural lands.

Although some human-generated intrusions have been linked to the decline of the bird, sustainable ranching can actually improve habitat. I saw first-hand the environmental benefits of wildlife-friendly grazing on the vast Wyoming ranch where I researched sage grouse. Since half of all remaining sage grouse reside on private lands, ranchers are the linchpin for maintaining healthy, intact range that these birds—and all sagebrush-dependent wildlife—rely upon.

Through the Sage Grouse Initiative, ranchers, industry leaders, nonprofit organizations, and local, state and federal government agencies are banding together under a shared vision: wildlife conservation through sustainable ranching. Conservation practices put in place on private rangelands include: implementing sustainable grazing systems, removing invading conifers, keeping lands intact through conservation easements, restoring and protecting wet meadows, and marking fences to prevent bird collisions.

Since 2010, the Sage Grouse Initiative has partnered with more than 1,500 ranchers to conserve over 5 million acres, an area twice the size of Yellowstone National Park.

In fact, this collaborative effort has proven so successful that the Natural Resources Conservation Service has since scaled-up its proactive, incentive-based sage grouse conservation model, and is now focusing Farm Bill funds in several other key landscapes across the nation. From salmon to cottontail rabbits, NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife is accelerating conservation on working farms and ranches in 30 states and across eight ecosystems.

Science-Based Success For Multiple Species

Part of the Sage Grouse Initiative’s recipe for success stems from the group’s reliance on applied science to guide project investments. By partnering with reputable scientists from universities and agencies across the nation—including scientists like my colleagues at the University of Montana—the Sage Grouse Initiative is able to strategically target conservation practices where they’re needed most. Plus, scientists also evaluate the resulting outcomes, helping to ensure conservation investments yield the most ecological benefits.

Co-producing science with organizations like the Boone and Crockett Club allows Sage Grouse Initiative to do more with less, maximizing Farm Bill dollars. The resulting science-based outcomes and targeting tools we produce together also make it easier for landowners and resource managers to plan and prioritize their next conservation projects.

Since sage grouse are considered an “umbrella species,” the Sage Grouse Initiative’s win-win conservation model extends benefits to a host of other wildlife, too—which, in turn, benefits hunters who enjoy hunting big game across sagebrush country.

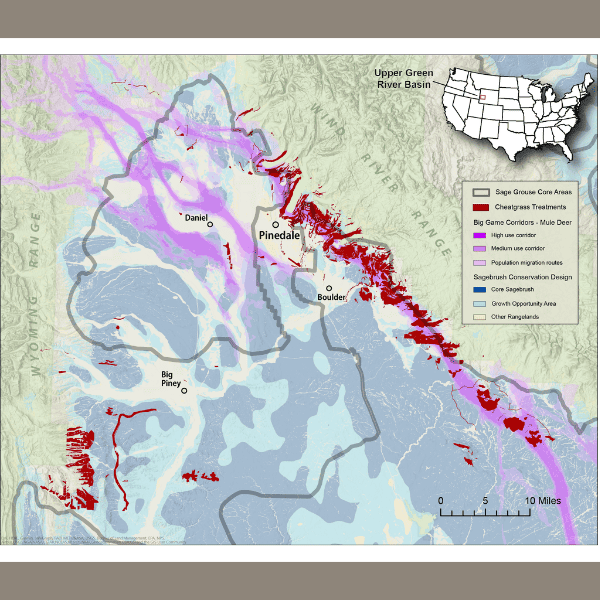

For instance, in Wyoming researchers found that conservation easements funded in part by the Sage Grouse Initiative also protect migratory pathways for mule deer, which also are affected by habitat conversion. One study showed that 75% of mule deer habitat is conserved through sage grouse conservation investments.

For instance, in Wyoming researchers found that conservation easements funded in part by the Sage Grouse Initiative also protect migratory pathways for mule deer, which also are affected by habitat conversion. One study showed that 75% of mule deer habitat is conserved through sage grouse conservation investments.

The same goes for elk. Of the 550,000 acres permanently protected by Sage Grouse Initiative-funded conservation easements, 52% of the land is within elk range. In particular, the Sage Grouse Initiative uniquely contributes to elk habitat conservation by protecting lower elevation sagebrush rangelands that elk use during the winter months.

As for pronghorn, University of Montana researchers recently discovered that antelope living along the border of Montana and Canada share their migratory pathways with sage grouse. Once again, Sage Grouse Initiative has cost-shared conservation easements that keep private working ranches intact to maintain this key migration corridor. These private lands provide stepping stones to adjacent public lands, which ensures these animals can access the habitat they need to survive and thrive on the range.

Researchers from the University of Montana also found that the abundance of songbird species, like the Brewer’s sparrow, increases by 50-80% in areas where expanding conifers are removed. Sage Grouse Initiative and its partners have removed juniper and pinyon-pine from over a half-million acres in the West, opening up prime sagebrush habitat for all sorts of upland birds and songbirds in addition to sage grouse.

Collaborative science like these studies in the sagebrush ecosystem are what teach us more about how the animals use the landscape and illustrate the value of partnerships with ranchers and the Sage Grouse Initiative.

Hopeful Hunting On The Range

This past June, I took my seven year-old son, Owen, to the Boone and Crockett Ranch for a weekend of fieldwork setting up wildlife cameras for a project intended to advance approaches for integrating ranching and wildlife management.

As we entered a grove of aspen, we spotted a ruffed grouse who was content to sit on a tree branch as we slowly went by. Owen reminded me that I promised to take him and his bird dog grouse hunting again, just like last year. He was already as excited as me about chasing upland birds. I hope Owen also has the opportunity to hunt sage grouse as well as ruffed grouse with his own children someday.

Thanks to the success of landscape-level conservation partnerships like the Sage Grouse Initiative, I’m hopeful that day will come sooner than later. Meanwhile, I’ll keep stalking the range for pronghorn, deer, and elk, grateful for the fact that the West still has healthy swaths of its beautiful sagebrush sea.