Patch-Burn Grazing Fires Up Prairie-Chicken Habitat

SCIENCE TO SOLUTIONS: Hot off the press! New research shows that patch-burn grazing creates the mosaic of grassland habitat structure that prairie-chickens depend on. LPCI’s latest Science to Solutions paper describes the research and its implications for range management.

Webinar: Effects Of Livestock Grazing On Sage Grouse Nesting Ecology

December 28, 2017The Conservation Gift That Benefits Us For Countless Years to Come

January 4, 2018For lesser prairie-chickens, good habitat is a complex thing. Structural diversity is key, because a prairie-chicken’s habitat needs change with the seasons. While courtship sites (leks) tend toward short-statured vegetation, females prefer to nest in tall, dense grassland vegetation, then move their chicks to more open, forb-dominated, insect-rich habitat.

New research shows that patch-burn grazing creates the mosaic of grassland habitat structure that prairie-chickens depend on. A new Science to Solutions paper from the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI) describes the research and its implications for range management.

Read the Science to Solutions story

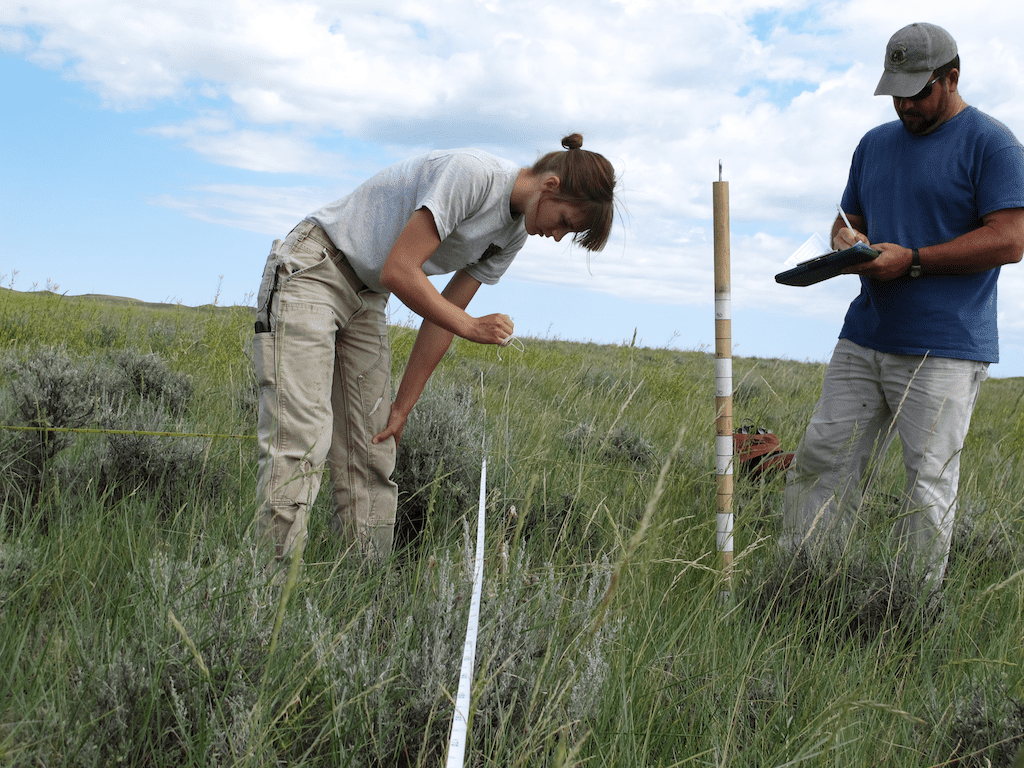

The research team, led by Jonathan Lautenbach of Kansas State University, addressed two central questions: How does patch-burn grazing influence grassland composition and structure? How do lesser prairie-chickens use the mosaic that patch-burn grazing creates?

Lautenbach found that, throughout the year, females chose vegetation patches where the combined effects of fire and grazing produced vegetation characteristics that matched their changing seasonal needs. Specifically, females selected greater time-since-fire patches (>2-years post-fire) for nesting, 2-year post-fire patches during the spring lekking season, 1- and 2-year post-fire patches during the summer brooding period, and 1-year post-fire units during the nonbreeding season.

Researchers have also found that patch-burn grazing yields good livestock performance by stabilizing weight gain in the face of rainfall fluctuations. That means patch-burn grazing offers a successful strategy to significantly improve both lesser prairie-chicken habitat and livestock production.

Historic Forces: The Dynamic Duo of Fire and Grazing

Historically, fire and grazing acted together to shape prairie vegetation. Ignited by Plains Indians and lightning, fire killed encroaching woody plants and prompted the vigorous re-sprouting and germination of prairie vegetation. This succulent new growth of grasses and forbs attracted herds of large herbivores, which selectively grazed the recently burned area. The resulting landscape was a mosaic of burned areas scattered among grassland patches of varied ages since burning.

Most current range management in the Great Plains decouples fire and grazing. When fire is over-applied (for example, by burning entire pastures), livestock don’t have the choice between burned and unburned prairie, and a uniform grassland structure results. On the other end of

the management spectrum, fire suppression also reduces grassland structural and species diversity.

Grassland uniformity reduces drought resiliency, which decreases livestock productivity. Uniformity also negatively impacts grassland wildlife, particularly grassland birds, since some species require varying vegetation structure across the landscape to complete their life cycles.

Further, without regularly occurring fires, fire-intolerant woody plants encroach, significantly reducing both livestock forage and grassland wildlife habitat (see LPCI’s Science to Solutions #1 on redcedar encroachment and Science to Solutions #3 on mesquite encroachment).

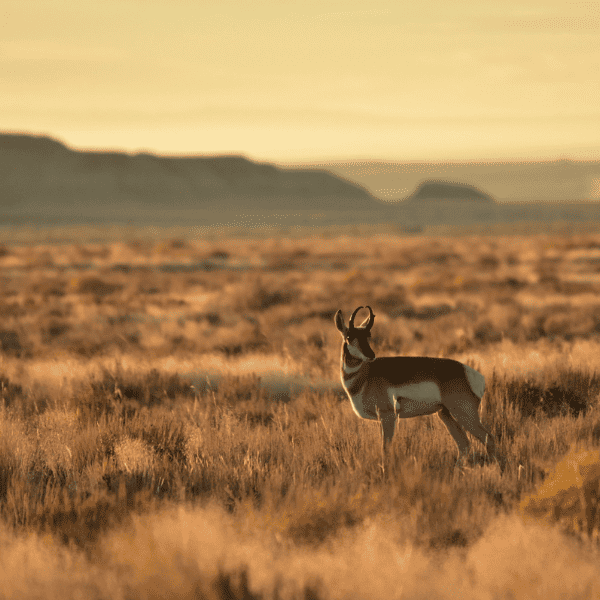

Male lesser prairie-chicken on a lek (mating display area) within the patch-burn grazing study area. The lek site had been burned just three days earlier. Photo: Jonathan Lautenbach.

What the Science Means for Management

The Natural Resources Conservation Service-led Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative provides technical and financial assistance to farmers and ranchers to voluntarily improve habitat for lesser prairie-chickens. Lautenbach’s study, funded in part by LPCI, helps identify which range management strategies are most effective in benefitting bird and herd.

Past research has shown the clear benefits of patch-burn grazing on livestock productivity. Specifically, cattle in pastures with two or more patches gained weight independent of rainfall, indicating that patch-burn grazing helps buffer climatic variation and stabilizes livestock productivity—a critically important attribute in the drought- prone southern Great Plains.

Also, research shows that, while both conventional prescribed burning and patch burning reduce wildfire fuels and redcedar encroachment, patch-burning does so while maintaining habitat for grassland-dependent wildlife.

Lautenbach’s study adds to evidence of the win-win nature of patch-burn grazing for livestock and wildlife, specifically showing that lesser prairie-chickens use the diverse patchwork to meet their needs for nesting, brood- rearing, and over-wintering.

The findings show that the scale and configuration of prescribed burns really matter. During the study, no females were observed nesting in year-of-fire patches, which lack thermal and hiding cover. Creating a mosaic of grassland patches of varied age-since-fire (rather than conventional whole-pasture burning) is a crucial part of the conservation equation.

To achieve the combined conservation strategies of removing redcedar and increasing grassland heterogeneity, Lautenbach’s research team recommends implementing prescribed fire in a patch-burn grazing system with a 4-6 year burn interval for any given patch.

The researchers note that their study was conducted in the eastern portion of the lesser prairie-chicken’s distribution. Regional differences in rainfall, soil types, and vegetation, create four different eco-regions, across the lesser prairie- chicken’s occupied distribution in the southern Great Plains. Within these ecoregions the recommended fire return interval will change, with areas receiving less rainfall having a greater fire-return interval (e.g. 7-10 years for any given patch).

Check out all of LPCI’s Science to Solutions papers on LPCI’s Resources page.