New Science: Sage Grouse Population Increases When Western Juniper Pushed Back

A new study funded in part by the NRCS-led Sage Grouse Initiative found that survival rates of both female sage grouse and their nests increased where encroaching juniper trees were removed.

Wildhorse Ranch Project: A Win-Win Partnership To Protect Sagebrush Range

April 21, 2017

Cherish The Soils And Roots That Support Life On The Range

May 4, 2017

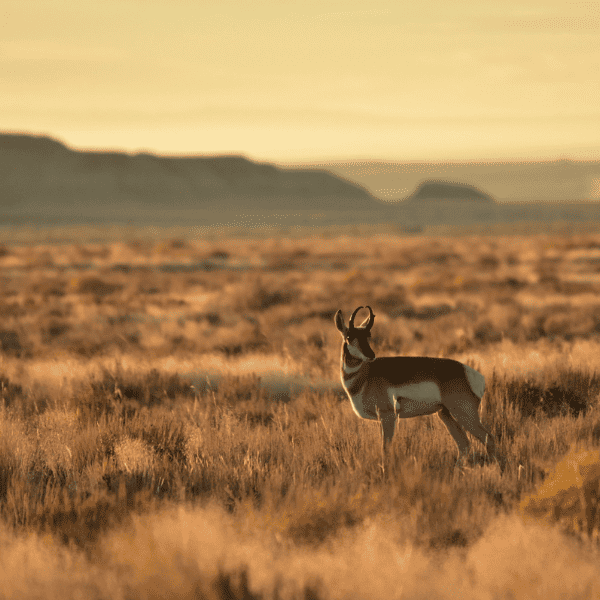

Greater sage-grouse photo courtesy Nick Myatt, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Where juniper was removed, female sage grouse annual survival increased by 6.6% and the nest survival rate increased by 18.8% each year

OSU College of Agricultural Sciences is a partner in the Sage Grouse Initiative, providing scientific research — like the following study on conifer removal — that informs our proactive, on-the-ground sagebrush conservation efforts on private ranchlands in the West.

By Chris Branam of Oregon State University

Greater sage grouse, a bird that been the subject of intense conservation efforts in recent decades, do better in areas where juniper trees have been removed, new research suggests.

This four-year study is the first to link sage grouse demographics with tree reduction and supports the idea of conserving sage grouse by controlling conifer expansion into the bird’s habitat. In the last half of the 20th century, the proliferation of the western juniper in Oregon and pinyon pine in Nevada and Utah degraded the sagebrush ecosystem by forming dense stands that suck up rainwater and push sagebrush out.

“We are tremendously excited,” said Christian Hagen, an avian ecologist at Oregon State University and a co-author of the study. “The arrow is pointing in the right direction. The grouse are finding these areas where the juniper was taken out much more quickly than we anticipated.”

This study focused on the encroachment of western juniper in southeast Oregon and just over the border in California and Nevada. Wildlife biologists in Oregon, Idaho and Montana estimated a 25 percent increase in the sage grouse population growth rate in an area where western juniper was being removed, either by cutting or burning, where juniper continued to spread slowly and the sage grouse population did not increase.

Removing conifers improves sagebrush habitat and water availability, benefiting birds and ranchers. Photo of a recent conifer cut in Montana by Dan Durham.

The researchers collected data on 219 female sage grouse and 225 nests from 2010 to 2014 in an area in southeast Oregon where western juniper was being removed and an area with no removal in southeast Oregon, northeast California and northwest Nevada. Both areas involved both public and private lands.

The annual survival of females from one breeding season to the next, and the survival of their nests over a month-long incubation period, both led to population growth over time, Hagen said. In the area where juniper was removed, female sage grouse annual survival increased 6.6 percent each year, and the nest survival rate increased by 18.8 percent each year.

Encroaching juniper degrades sage grouse habitat in two ways: by outcompeting the sagebrush and by introducing trees that the birds consider threatening, said Hagen, a senior researcher in the College of Agricultural Sciences.

“Dense tree stands become perches and hiding cover for predators, so sage grouse avoid them,” Hagen said.

The trees that were removed were less than a hundred years old, Hagen said. Most of the juniper was cut down by hand-cutting and chainsaws and generally occurred from late fall to early spring, to both maximize shrub retention and minimize negative effects to grouse breeding activities.

The study was led by John Severson, who conducted the research for his dissertation at the University of Idaho. The research was funded by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, through its Conservation Effects Assessment Project and Sage Grouse Initiative.

Read the new study: “Better living through conifer removal“

Read SGI’s Science to Solutions: “Conifer Removal Boosts Sage Grouse Success“

Watch replays of presentations at the recent “Woodland Expansion Symposium”