COOL GREEN SCIENCE | The Stream Whisperer Restores Sage Grouse Habitat

by Brianna Randall | Bill Zeedyk teaches Westerners how to “think like water” to restore precious wet habitat in the sagebrush desert.

New State of the Birds Report: Farm Bill Pays Off For People & Birds

August 10, 2017

Grazing Management In Perspective: A Compatible Tool For Sage Grouse Conservation

August 28, 2017

Photo of Gunnison sage-grouse by Lance Beeney

This story by Brianna Randall originally appeared in Cool Green Science

People in the Gunnison Basin of Colorado call Bill Zeedyk the stream whisperer. The first time I met him, he certainly seemed magical.

Zeedyk looks like a shorter version of Gandalf, with a long white beard, battered leather hat, and an ubiquitous wooden staff, which he uses both as a walking stick and as a visual aid to point out precious wet areas in the sagebrush desert.

Water is the limiting factor out West, the not-so-secret sauce that can make or break conservation efforts on behalf of struggling species like the threatened Gunnison sage-grouse.

Sage grouse hens and their broods rely on the “green groceries”—protein-rich insects and forbs—found near springs, wet meadows, streamsides, and other wet places to feed the growing chicks during late summer and early fall.

But what’s at stake is so much more than just a bird.

Wet, green spots on the landscape comprise only 1-2% of the western landscape, but 80% of animals depend on them.

These rare emerald isles in a sea of sagebrush sustain working lands and wildlife across millions of acres. They provide drought insurance for ranchers and critical food for hungry animals when the snowpack is gone and there’s no rain in sight.

Think Like Water

I joined 170 resource managers in Gunnison to learn from the stream whisperer. We gathered beneath the blinding high-elevation sun to hear how conservation partners in southwestern Colorado are restoring wet meadows to benefit the bird and the herd.

“You have to learn to think like water,” Zeedyk told us. Noticing our befuddled expressions, he chuckled and tried again. “Okay, then, let’s start with reading the landscape.”

We were standing on the edge of a small pond that drained into a three-acre wetland complex. Sedges and rushes outlined the path of the water, bordered by green grasses and wildflowers. All of this lush habitat was surrounded by dry-as-dust soil and the redolent sagebrush that defines the West.

The workshop was sponsored by the Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI)—a partnership-based, science-driven effort led by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, which uses voluntary incentives to proactively conserve working lands. SGI released its Mesic Conservation Strategy in April to help ranchers protect and enhance the wet places that sustain life on the range.

As part of the strategy, SGI looked for simple, low-cost alternatives for restoring wet habitats. Enter “Zeedyk structures,” which we traveled here to see.

After working for the U.S. Forest Service for 34 years, Bill and his wife founded Zeedyk Ecological Consulting, LLC in 2004 to restore small streams and wetlands in the Southwest. He’s been helping the Gunnison Climate Working Group improve natural water storage since 2012.

“What we’re trying to do is restore habitat, store water in the soil, and moderate the flows so that runoff lasts longer,” said Zeedyk.

Zeedyk pointed out a nearby road and cattle prints in the mud, explaining how the West has lost much of its wet habitat. Cows and humans tromp through streams in search of water or to access fields, causing erosion. In turn, stream channels get deeper and steeper — a term called “headcutting.”

As water cuts down and incises the channel, it takes the groundwater with it, drying out the floodplain and erasing precious habitat.

“Here, we needed to make the meadow level again by filling in those steep gullies,” said Zeedyk. “Follow me, and I’ll show you how we did it.”

Simple Restoration Structures

Zeedyk took us to a series of structures created out of nearby rocks and dirt. Not one for poetry, his designs are named simply: one-rock dam, rock rundown, media luna. (The last one, a layer of rocks spread across the streambed in a half-moon shape, was actually named by Spanish-speaking volunteers in New Mexico.)

He also showed us a Zuni bowl, used by the indigenous people for centuries to disperse flows and dissipate the energy of falling water.

Though shaped differently, these easy-to-install restoration structures all have the same end results: they capture sediment, raise the water table, and reconnect streams to their floodplains.

And all of them can be completed in a day by a half-dozen volunteers using shovels and gloves.

Another positive: Zeedyk’s structures blend in with the natural environment. I could barely see the rocks at one site we visited, restored in 2014. They had already disappeared beneath new plants and dirt.

To get the most ecological bang for the buck, the Gunnison Climate Working Group designs watershed-scale projects. That means working across multiple public and private land ownership boundaries to install rock structures.

Typically, degraded streams required 20 to 40 structures placed between 5 and 20 feet apart. The structures are usually less than one foot in height, and custom-designed to fit each unique stream reach.

Thanks to teams of volunteers from Western Colorado Conservation Corps and Wildlands Restoration Volunteers, it generally takes just one week to repair an entire drainage.

Zeedyk and Shawn Conner, restoration ecologist with BIO-Logic, Inc., help train these volunteers.

“It’s a lot like masonry work,” Zeedyk said. “We key together rock like a puzzle. There’s an art to it.”

Fit the River

Before they met Zeedyk, resource managers in the Gunnison Basin tried using brute force to hold water in place. The field tour included a trip to a series of gabion structures installed a decade ago—dams across the channel created by building a big wire cage filled with tons of rock.

But these cages cost upwards of $10,000 a pop (not including the engineering fees), and one gully often needed a half-dozen dams to achieve the desired ecological effect.

“Bill straightened us out,” laughed Nate Seward, a terrestrial biologist with Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

Seward says that Zeedyk’s structures have “less blowouts” than the gabion dams. This is partly because the low-profile design ensures that the structures get more stable as sediment and vegetation grow on top, anchoring them into the channel.

One caveat, Zeedyk warned, is that these strucutres are designed to work where headcutting is less than three feet deep. Once erosion gets deeper than that, you need bigger, more complicated structures that have less chance of success.

“If you build modest structures that fit the river, then the river will go along with you,” Zeedyk told us.

Science-based Solutions

The Gunnison Climate Working Group launched its Wet Meadow Restoration Project in 2012. This ad-hoc group comprised of local landowners, scientists and practitioners formed in 2009 after The Nature Conservancy of Colorado hosted a workshop to discuss how best to prepare for more frequent droughts and floods.

The group prioritized improving natural water storage as a solution for Gunnison communities.

“We wanted to work at a scale large enough to help sagebrush-dependent wildlife like the Gunnison sage-grouse, deer, and elk, as well as the ranchers who depend on this landscape for their livelihoods,” said Betsy Neely, Climate Change Program Manager for the Conservancy’s Colorado Field Office in Boulder.

The results have been impressive. Since 2012, the group has installed 1,112 simple restoration structures, restoring 21 miles of habitat across eight watersheds.

And they’re just getting started. Zeedyk told us they’ve identified an additional 120 miles for future restoration work.

Partners in Gunnison used a science-based approach to target where to work in the 2.5 million-acre basin. Teresa Chapman, GIS Manager for The Nature Conservancy of Colorado, analyzed NDVI satellite data as a way to measure the greenness of wet habitats since 2000.

Chapman located stream reaches that were “very green” during wet years, but didn’t “green up” at all during drought years. These were the most at-risk areas given changing climactic conditions, and had the best potential for responding well to restoration efforts.

On top of that data, Chapman added in the locations of known sage grouse leks (breeding sites). This helped the group focus restoration in places where keeping more water on the landscape would “give the birds a leg up” during difficult climactic years.

A Different Dance

Part of the motivation behind restoring wet meadows in the Gunnison Basin was the fact that access to mesic habitat is a limiting factor in the life cycle of Gunnison sage-grouse.

Found only in southwestern Colorado and southeastern Utah, Gunnison sage-grouse occupy just 7-10% of their historic range. Although the largest subpopulation is relatively stable — thanks in large part to the voluntary conservation efforts of local ranchers and partners in Gunnison — the other six satellite populations have shown long-term declines.

Gunnison sage-grouse are only two-thirds the size of their more widely dispersed cousin, the greater sage-grouse. They also have different banding patterns on their tail feathers as well as prominent ponytail feathers, called filoplumes.

Their dance is different, too. Male Gunnison sage-grouse wag their tails at the end of their display, and also pop their air sacs several more times than greater sage-grouse.

But like all sage grouse, the Gunnison species relies on wide-open, intact habitat dominated by sagebrush. Plus, hens need reliably wet areas to fatten up their chicks before winter sets in.

Studies have shown that chicks who have to transition earlier in the fall to a diet of solely sagebrush leaves have a lower survival rate than those that eat insects and forbs longer.

Role of Ranchers

Although only 15% of the Gunnison Basin is privately owned, ranchers own most of the land along creeks and streams.

“Private ranchers are some of our best champions, because they see results so quickly on the ground,” explained Neely. “Their neighbors notice the difference and want to join in, too.”

Typically, most restoration sites begin to show a significant response around three years after installing the structures. But you can generally see some response within just one year.

Early adopters in Gunnison can’t speak highly enough about the positive results.

Jim Cochran, a local rancher, told us, “This was a no-regrets project. It keeps water on my land, and keeps water in the basin.”

Liz With represents the Natural Resources Conservation Service on the Gunnison Climate Working Group. She helps ranchers cost-share Zeedyk structures using Farm Bill conservation programs.

According to With, the ranchers involved in this project see the importance of storing more water in the ecosystem. The structures also help maintain a good mix of plant species that provide nutritious forage for their cattle and keep noxious weeds at bay.

The Grass is Greener

To measure the ecologic response, three members of the Gunnison Climate Working Group—Renee Rondeau, an ecologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Gay Austin, ecologist with BLM, and Suzanne Parker, biologist with USFS—have been monitoring restoration treatments since the project’s inception.

“The group’s goal was to increase wetland species cover by 20 percent at each structure. We’ve definitely exceeded that,” said Rondeau.

At sites built the first year in 2012, Rondeau’s data shows an average increase of 160 percent in wetland species cover in just four years at the restored sites.

The group uses monitoring data to help adjust and maintain the structures. For instance, some sites require a second layer of rocks to increase sediment capture and vegetation growth.

“We don’t just put the structures in and walk away,” said Neely. “The highest success rate means tweaking the structures until they work best for each landowner and each landscape.”

SGI’s science team also assessed the outcomes of recent mesic habitat restoration in Gunnison to help fine-tune delivery as it expands to other watersheds in the West. Nick Silverman, SGI hydrologist, found a 24% increase in late summer greenness post-restoration.

Scaling Up

The Upper Gunnison Water Conservancy District recently took over the coordination role for wet meadow restoration work so that The Nature Conservancy can scale up the project to watersheds in need across the West.

The SGI workshop was a helpful step in transferring Zeedyk’s habitat restoration knowledge—or, dare I say, magic—beyond the Gunnison Basin.

Liz With receives phone calls from other NRCS field offices asking how to replicate the use of Zeedyk’s simple, cost-effective structures. She believes that the opportunity to transfer these restoration methods across the 11-state range of greater sage-grouse is “limitless and overwhelmingly beneficial.”

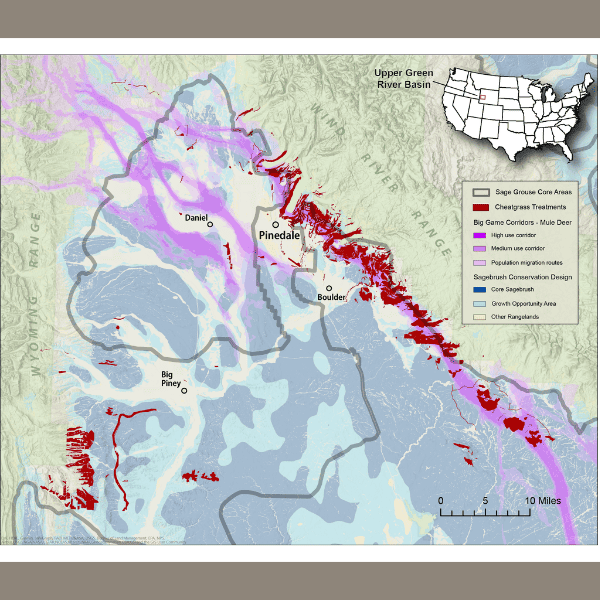

To help target where to invest in enhancing wet habitats, SGI recently released a Mesic Resources Layer as part of its Interactive Web App, a free online mapping tool that shows where mesic areas are and how they fluctuate through time.

“We want to eventually use NRCS and other conservation programs to put these tools into the hands of every rancher who’s interested in restoring wet habitat,” said With.