The Story of Saving the Loess Canyons

A new report highlights how landowners in the Loess Canyons of Nebraska have successfully reversed tree encroachment in grasslands while also facilitating co-produced science to inform and improve future management of the Great Plains’ grassland biome.

Publication: Habitat Preferred by Sage Grouse Increases Six-Fold Following Tree Removal

October 20, 2021

Warners

November 23, 2021

Well-organized, community-led groups comprised of local landowners, fire professionals, and land management agencies is a key aspect of safely conducting prescribed burning in the Loess Canyons. Photo: Christine Bielski.

Landscapes like this treeless expanse of the Loess Canyons in Nebraska require regular, proactive fire management to remove both encroaching trees like eastern redcedar and their seeds. Photo: Dillon Fogarty.

Landscapes like this treeless expanse of the Loess Canyons in Nebraska require regular, proactive fire management to remove both encroaching trees like eastern redcedar and their seeds. Photo: Dillon Fogarty.

This story originally appeared in the Loess Canyons Experimental Landscape Science Report, a publication of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln produced with support from Working Lands for Wildlife (published October 2021). Find the full report here.

By Brianna Randall

When Mark Alberts’ dad and grandparents used to go in search of their family Christmas tree, it often took hours to hunt down a lone redcedar in southwestern Nebraska. Unfortunately, redcedars have since taken over much of America’s fertile prairie. The rangelands south of the Platte River valley are now one the most tree-infested areas in Nebraska.

The rapid invasion of eastern redcedar across America’s Great Plains spells bad news for landowners and communities that rely on grass. These trees replace native grasses, which means less food for livestock and less revenue for ranchers.

“It’s called the ‘green glacier’ since the trees are invasive and grow so fast,” said Alberts, a 63-year-old farmer and rancher who has lived in Nebraska’s Loess Canyons his whole life. “The problem keeps compounding. Grandpa and Dad used to run 80 calf-cow pairs on a section of grass. But when that section is half covered by trees, it can’t feed as many cattle.”

This is not how the grasslands of the Great Plains are supposed to look. Encroachment like this is extremely difficult to reverse and requires experienced and well-coordinated prescribed fire management. Photo: Christine Bielski.

Not only do the invading trees cut into ranchers’ productivity, but they also displace grassland wildlife, like bobwhite quail and prairie chickens. Plus, redcedars steal precious water from streams and aquifers—each tree can consume up to 40 gallons per day. Denser trees also cause hotter, more intense wildfires that threaten property and people.

FIGHTING TREES WITH FIRE

Over two decades ago, Alberts and some of his neighbors decided to take action to save the grassland and their livelihoods. Some tried cutting redcedar with chainsaws or other machines, but it barely made a dent in the thicket. Instead, they turned to prescribed fire.

Grasslands evolved with frequent fires, which help recharge soil nutrients and spur new plants to grow. Historically, Nebraska’s prairies burned every few years due to lightning strikes or Indigenous communities who lit fires to lure in bison and other game with fresh, green, post-burn grass. Without flames to relegate trees to wet or rocky areas, redcedars have inexorably marched across grasslands over the past 150 years.

Prescribed fires, like this one, not only remove encroaching eastern redcedar trees, they also restore nutrients to the soil, benefiting native grasses, wildlife, and ranchers who rely on healthy, productive rangelands. Photo: Andy Moore.

Other landowners in the Great Plains were already using prescribed burns to prevent small saplings from becoming seed-dispersing trees. But the landowners in the Loess Canyons took it a step further—they decided to see if fire could restore rangeland after redcedars had already matured and spread.

Mark Alberts, the “guinea pig,” and a leader in the Loess Canyons. Photo courtesy of Mark Alberts.

Mark Alberts was the guinea pig. In 2000, a handful of other landowners and representatives from the NRCS helped him burn 300 acres. It worked like a charm, killing the trees and opening up his pasture. Alberts was able to run 10- 15% more cattle when the grass grew back the following year.

But Alberts says that most of his neighbors “watched with clenched teeth,” including his uncle who lived across the fence. They were afraid the fire would get out of control and doubted its ability to help rather than harm the land.

“What’s amazing is how nearly every one of those neighbors has come around,” Alberts said. “Even my uncle burned one of his pastures after seeing that the trees didn’t come back on my flats.”

LOCAL LEADERS ARE KEY TO SUCCESS

Doug Whisenhunt, then a district conservationist with USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), helped orchestrate that first burn. A few years later, he helped Alberts and a dozen other landowners form the Loess Canyons Rangeland Alliance (LCRA), a group dedicated to using fire as a land management tool.

The LCRA now includes nearly 100 members who share equipment, time, and expertise to burn grasslands and keep trees at bay. Whisenhunt said a major turning point for motivating more interest in prescribed fire was when Scott Stout, then in his mid-30s, took over as the burn boss and president of the LCRA.

“As a local rancher and social leader, he was the right guy to make it successful,” added Wisenhunt. “If your burn boss isn’t local, no one follows them—and you can’t be a leader if no one follows you.”

Participation and interest in prescribed fire grew so much that landowners formed a second burn group in 2008, the Central Platte Rangelands Alliance. Collectively, landowners in both groups have burned 135,000 acres in the Loess Canyons, which represents one-third of the total landscape.

“We’re all on the same page, trying to regain what we have lost. We trade labor and equipment back and forth, just like at a branding,” said Scott Stout, who is now president of the Nebraska Prescribed Fire Council. “It’s really brought back a sense of camaraderie among neighbors.”

Alberts reflected that “neighboring together better” is just one of the many benefits that came about as a result of reinstating fire.

PARTNERS PONY UP TO SUPPORT LANDOWNERS

The nutritious new grasses that come in after a prescribed burn are also a boon to wildlife like songbirds, turkey, and deer. T.J. Walker is a wildlife biologist with Nebraska Game and Parks Commission who has worked with the Loess Canyons burn groups for over two decades. He stresses the importance of supporting landowner-led conservation since 97 percent of Nebraska is privately owned.

“We want to help the ranchers help themselves because their land provides a lot of great wildlife habitat,” said Walker. “If we aren’t managing the cedars, they’re going to take over those grasslands and drastically reduce biodiversity across the board.”

Walker credited the landowners and their commitment to each other as the main reason the Loess Canyons still have healthy, intact grasslands. But another not-so-secret ingredient to their success is strong partnerships between state and federal agencies and non-profits that provided landowners with financial and technical support.

The Nebraska Environmental Trust helped the LCRA purchase water tanks, drip torches, and all-terrain vehicles with sprayers. NRCS provides cost-share for landowners to defer grazing on the pastures they plan to burn. Pheasants Forever, USFWS Partners for Fish and Wildlife, and Nebraska Game and Parks Commission also contribute funds to help landowners prepare burn units, which includes cutting isolated redcedars beforehand and “stuffing” them under dense cedar patches to provide fires with extra fuel for killing more mature trees. Using fire after cutting larger trees ensures that any seeds or small seedlings hidden in the grass are burned, which prevents a new generation of trees from rapidly re-encroaching.

Cutting some eastern redcedar trees and “stuffing” them under thick stands helps fires burn hotter, killing mature trees and the seeds lying on the ground. Photo: Christine Bielski

Through good communication and the willingness to work together, these partners merged their efforts into one collective vision: restore healthy rangelands by removing invading eastern redcedar with prescribed fire.

SCIENCE THAT’S PART OF THE FAMILY

The unique collaborative conservation work in the Loess Canyons drew the attention of Dirac Twidwell, a rangeland ecologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“Most research is done on small experimental plots,” he said. “I was searching for examples of landowners using fire across properties and managing at larger scales to address woody encroachment.”

In 2014, Twidwell met with 20 ranchers at a steakhouse in Curtis, Nebraska, to see how researchers and landowners might learn from each other in the Loess Canyons. Landowners were so hungry for information that they talked with Twidwell for hours that night.

Following the meeting, Twidwell and the landowner group agreed to establish a private lands experimental landscape in the Loess Canyons covering approximately 180,000 acres.

“It’s one of the largest experimental landscapes in Great Plains grasslands and one of the only ones owned entirely by private landowners,” Twidwell explained.

Twidwell immediately took advantage of long-term monitoring data collected by NGPC and partners and implemented new field studies with graduate students. Since 2015, over a dozen students have collected data in the Loess Canyons Experimental Landscape. As evidence of the trust between scientists and ranchers, landowners even let students stay in their spare rooms or basements while they’re conducting research over the summer.

“We often talk about scientific co-production or use-inspired science,” said Twidwell. “This is a preeminent model of how to successfully work with landowners at large scales. It meets the land-grant mission of the University of Nebraska in the truest sense. We feel part of the family and the community. It’s not just scientific conclusions. The science supports the cultural fabric of the region and goes way beyond science produced solely from an ivory tower.”

The co-production of science in the Loess Canyons is providing key insights into how prescribed fire benefits grasslands and is only possible through the continued partnerships of landowners, universities, and groups like Working Lands for Wildlife. Photo courtesy of Christine Bielski.

IGNITING INTEREST WORLDWIDE

The community-based, co-production of science in the Loess Canyons includes the input and participation of groups like the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission.

“We don’t want to do research in a vacuum, we want to do it in tandem with partners to give people the information they need to help manage the resource,” said Walker.

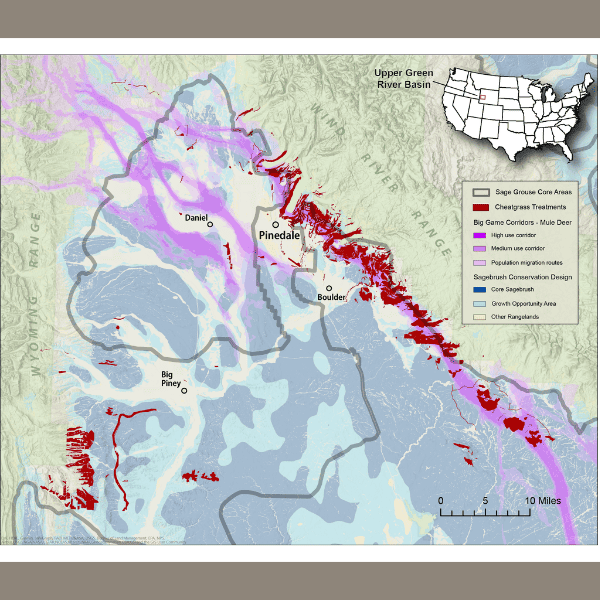

Walker and his colleagues are now using models created by Twidwell’s lab at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to target grasslands conservation across the state. For instance, they can identify areas most at risk from encroaching redcedar, as well as where to invest money to protect core habitat that is treeless.

Now that story is spreading far beyond Nebraska. Twidwell, Walker, and local landowners are mentoring resource managers who are struggling to contain trees taking over grasslands.

“This problem is worldwide,” said Alberts. “People in Spain, Portugal, South Africa, they all want to know how we do it. They want us to teach them how to do prescribed burning safely to get back their grass, and also to minimize the risk of catastrophic wildfires.”

The science from the Loess Canyons also informed the first-ever, biome-scale framework for conservation action in the Great Plains, recently released by NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife. The aim is to clone the model of collaborative success in the Loess Canyons to help other landowners address threats in their region.

Meanwhile, Alberts, Stout, and hundreds of other landowners in the Loess Canyons—from great-grandparents down to young children—will continue to work side-by-side to use fire as a tool to improve their rangelands.

“I don’t want my kids or grandkids to say, ‘Why didn’t Dad take care of those when he could?’” Stout said. “The time to get them is now.”

Well-organized, community-led groups comprised of local landowners, fire professionals, and land management agencies is a key aspect of safely conducting prescribed burning in the Loess Canyons. Photo: Twidwell Lab.

>>Read the Loess Canyons Experimental Landscape Science Report<<

More resources:

Explore the recently published “Reducing Woody Encroachment in Grasslands: A Guide for Understanding Risk and Vulnerability” to learn more about woody encroachment in the Great Plains.

Learn more about how WLFW is helping landowners retain and restore grasslands across the Great Plains in the Framework for Conservation Action in the Great Plains Grasslands Biome.